Dubois E., Gray P., Nigay L. (Eds.) The Engineering of Mixed Reality Systems

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

356 V. Sta n t chev

30. A. Polze, J. Schwarz, and M. Malek. Automatic generation of fault-tolerant corba-services.

tools, 00:205, 2000.

31. M.D. Rodriguez, J. Favela, E.A. Martinez, and M.A. Munoz. Location-aware access to hospi-

tal information and services. IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine,

8(4):448–455, Dec. 2004.

32. W.S. Sandberg, B. Daily, M. Egan, J.E. Stahl, J.M. Goldman, R.A. Wiklund, and D. Rattner.

Deliberate perioperative systems design improves operating room throughput. Anesthesiology,

103(2):406–18, 2005.

33. V. Stantchev. Architectural Translucency. GITO Verlag, Berlin, Germany, 2008.

34. V. Stantchev, T.D. Hoang, T. Schulz, and I. Ratchinski. Optimizing clinical processes with

position-sensing. IT Professional, 10(2):31–37, 2008.

35. V. Stantchev and M. Malek. Architectural translucency in service-oriented architectures. IEE

Proceedings - Software, 153(1):31–37, February 2006.

36. V. Stantchev and M. Malek. Translucent replication for service level assurance. In High

Assurance Service Computing (to appear), pages 127–148, Berlin, New York, 04 2009.

Springer.

37. V. Stantchev and C. Schröpfer. Techniques for service level enforcement in web-services

based systems. In Proceedings of The 10th International Conference on Information

Integration and Web-based Applications and Services (iiWAS2008), pages 7–14, New York,

NY, USA, 11 2008. ACM.

38. V. Stantchev, T. Schulz, and T.-D. Hoang. Ortungstechnologien im op-bereich. In Mobiles

Computing in der Medizin (MoCoMed) 2007: Proceedings of the 7th Workshop on, pages

20–33, Aachen, Germany, 2007. Shaker.

39. C. Varela and G. Agha. Programming dynamically reconfigurable open systems with salsa.

SIGPLAN Not., 36(12):20–34, 2001.

40. S. Weerawarana, F. Curbera, F. Leymann, T. Storey, and D.F. Ferguson. Web Services Platform

Architecture: SOAP, WSDL, WS-Policy, WS-Addressing, WS-BPEL, WS-Reliable Messaging

and More. Prentice Hall PTR Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2005.

41. E. Weippl, A. Holzinger, and A.M Tjoa. Security aspects of ubiquitous computing in health

care. e & i Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik, 123(4):156–161, 2006.

Chapter 18

The eXperience Induction Machine: A New

Paradigm for Mixed-Reality Interaction Design

and Psychological Experimentation

Ulysses Bernardet, Sergi Bermúdez i Badia, Armin Duff, Martin Inderbitzin,

Sylvain Le Groux, Jônatas Manzolli, Zenon Mathews, Anna Mura,

Aleksander Väljamäe, and Paul F.M.J Verschure

Abstract The eXperience Induction Machine (XIM) is one of the most advanced

mixed-reality spaces available today. XIM is an immersive space that consists of

physical sensors and effectors and which is conceptualized as a general-purpose

infrastructure for research in the field of psychology and human–artifact interaction.

In this chapter, we set out the epistemological rational behind XIM by putting the

installation in the context of psychological research. The design and implementation

of XIM are based on principles and technologies of neuromorphic control. We give a

detailed description of the hardware infrastructure and software architecture, includ-

ing the logic of the overall behavioral control. To illustrate the approach toward

psychological experimentation, we discuss a number of practical applications of

XIM. These include the so-called, persistent virtual community, the application

in the research of the relationship between human experience and multi-modal

stimulation, and an investigation of a mixed-reality social interaction paradigm.

Keywords Mixed-reality · Psychology · Human–computer interaction · Research

methods · Multi-user interaction · Biomorphic engineering

18.1 Introduction

The eXperience Induction Machine (XIM, Fig. 18.1) located in the Laboratory

for Synthetic Perceptive, Emotive and Cognitive Systems (SPECS) in Barcelona,

Spain, is one of the most advanced mixed-reality spaces available today. XIM is

a human-accessible, fully instrumented space with a surface area of 5.5 × 5.5 m.

The effectors of the space include immersive surround computer graphics, a lumi-

nous floor, movable lights, interactive synthetic sonification, whereas the sensors

U. Bernardet (B)

SPECS@IUA: Laboratory for Synthetic Perceptive, Emotive, and Cognitive Systems, Universitat

Pompeu Fabra, 08018 Barcelona, Spain

e-mail: bernuly@gmail.com

357

E. Dubois et al. (eds.), The Engineering of Mixed Reality Systems, Human-Computer

Interaction Series, DOI 10.1007/978-1-84882-733-2_18,

C

Springer-Verlag London Limited 2010

358 U. Bernardet et al.

include floor-based pressure sensors, microphones, and static and movable cameras.

In XIM multiple users can simultaneously and freely move around and interact with

the physical and virtual world.

Fig. 18.1 View into the eXperience Induction Machine

The architecture of the control system is designed using the large-scale neuronal

systems simulation software iqr [1]. Unlike other installations, t he construction of

XIM r eflects a clear, twofold research agenda: First, to understand human expe-

rience and behavior in complex ecologically valid situations that involve full body

movement and interaction. Second, to build mixed-reality systems based on our cur-

rent psychological and neuroscientific understanding and to validate these systems

by deploying them in the control and realization of mixed-reality systems.

We will start this chapter by looking at a number of mixed-reality system, includ-

ing XIM’s precursor, “Ada the intelligent” space, built in 2002 for the Swiss national

exhibition Expo.02.

XIM has been designed as a general-purpose infrastructure for research in the

field of psychology and human–artifact interaction (Fig. 18.2). For this reason, we

will set out the epistemological rationale behind the construction of a space like

XIM. Here we will give a systemic view of related psychological research and

describe the function of XIM in this context.

Subsequently we will lay out the infrastructure of XIM, including a detailed

account of the hardware components of XIM, the software architecture, and the

overall control system. This architecture includes a multi-modal tracking system,

the autonomous music composition system RoBoser, the virtual reality engine, and

the overall neuromorphic system integration based on the simulator iqr.

To illustrate the use of XIM in the development of mixed-reality experience and

psychological research, we will discuss a number of practical applications of XIM:

The persistent virtual community (Fig. 18.2), a virtual world where the physical

world is mapped into and which is accessible both from XIM and remotely via a

desktop computer; the interactive narrative “Autodemo” (Fig. 18.2); and a mixed-

reality social interaction paradigm.

18 The eXperience Induction Machine 359

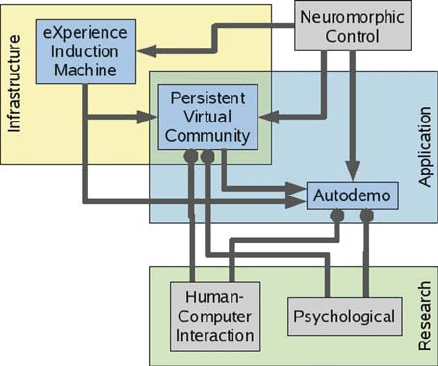

Fig. 18.2 Relationship between infrastructure and application. The eXperience Induction Machine

is a general-purpose infrastructure for research in the field of psychology and human–artifact

interaction. In relation to XIM, the persistent virtual community (PVC) is on the one hand an

infrastructure insofar as it provides a technical platform, and on the other hand an application as it

is built on, and uses, XIM. The project “Autodemo,” in which users are guided through XIM and

the PVC, in t urn is an application which covers aspects of both XIM and the PVC. In the design

and implementation both XIM and the Autodemo are based on principles and technologies of neu-

romorphic control. PVC and Autodemo are concrete implementations of research paradigms in the

fields of human–computer interaction and psychology

18.1.1 Mixed-Reality Installations and Spaces

A widely used framework to classify virtual and mixed-reality systems is the “vir-

tuality continuum” which spans from “real environment” via “augmented reality”

and “augmented virtuality” to “virtual environment” [2]. The definition of mixed

reality hence includes any “paradigm that seeks to smoothly link the physical and

data processing (digital) environments.” [3]. With this definition, a wide range of

different installations and systems can be categorized as “mixed reality,” though

these systems fall into different categories and areas of operation, e.g., research in

the field of human–computer interaction, rehabilitation, social interaction, educa-

tion, and entertainment. Depending on their use and function, the installations vary

in size, design, number of modalities, and their controlling mechanisms. A common

denominator is that in mixed-reality systems a physical device is interfaced with a

virtual environment in which one or more users interact. Examples of such installa-

tions are the “jellyfish party,” where virtual soap bubbles are generated in response

to the amount and speed of air expired by the user [4], the “inter-glow” system,

where users in real space interact using “multiplexed visible-light communication

technology” [5], and the “HYPERPRESENCE” system developed for control of

multi-user agents – robot systems manipulating objects and moving in a closed, real

360 U. Bernardet et al.

environment – in a mixed-reality environment [6]. Frequently, tangible technology

is used for the interface as in the “Touch-Space” [7] and the “Tangible Bits” [8]

installations.

Many of the above-mentioned systems are not geared toward a specific applica-

tion. “SMALLAB,” “a mixed-reality learning environment that allows participants

to interact with one another and with sonic and visual media through full body, 3D

movements, and vocalizations” [9], and the “magic carpet” system, where pressure

mats and physical props are used to navigate a story [10], are examples of system

used in the educational domain.

Systems designed for application in the field of the performing arts are the

“Murmuring Fields,” where movements of visitors trigger sounds located in the

virtual space which can be heard in the real space [11], and the “Interactive Theatre

Experience in Embodied + Wearable mixed-reality Space.” Here “embodied com-

puting mixed-reality spaces integrate ubiquitous computing, tangible interaction,

and social computing within a mixed-reality space” [12].

At the fringe of mixed-reality spaces are systems that are considered “intelligent

environments,” such as the “EasyLiving” project at Microsoft Research [13] and the

“Intelligent Room” project, in which robotics and vision technology are combined

with speech understanding systems and agent-based architectures [14]. In these sys-

tems, the focus is on the physical environment more than on the use of virtual

reality. Contrary to this, are systems that are large spaces equipped with sophisti-

cated VR displays such as the “Allosphere Research Facility,” a large (3-story high)

spherical space with fully immersive, interactive, stereoscopic/pluriphonic virtual

environments [15].

Examples of installations that represent prototypical multi-user mixed-reality

spaces include Disney’s indoor interactive theme park installation “Pirates of the

Caribbean: Battle for Buccaneer Gold.” In this installation a group of users are on a

ship-themed motion platform and interact with a virtual world [16]. Another exam-

ple is the “KidsRoom” at MIT, a fully automated, interactive narrative “playspace”

for children, which uses images, lighting, sound, and computer vision action

recognition technology [17].

One of the largest and most sophisticated multi-user systems, and the pre-

cursor of XIM, was “Ada: The Intelligent Space,” developed by the Institute of

Neuroinformatics (INI) of the ETH and the University of Zurich for the Swiss

national exhibition Expo.02 in Neuchâtel. Over a period of 6 months, Ada was

visited by 560,000 persons, making this installation the largest interactive exhibit

ever deployed. The goal of Ada was, on the one hand, to foster public debate on

the impact of brain-based technology on society and, on the other hand, to advance

the research toward the construction of conscious machines [18]. Ada was designed

like an organism with visual, audio, and tactile input, and non-contact effectors in

the form of computer graphics, light, and sound [19]. Conceptually, Ada has been

described as an “inside out” robot, able to learn from experience, react in a goal-

oriented and situationally dependent way. Ada’s behavior was based on a modeled

hybrid control s tructure that includes a neuronal system, an agent-based system, and

algorithmic-based processes [18].

18 The eXperience Induction Machine 361

The eXperience Induction Machine described in this chapter is an immersive,

multi-user space, equipped with physical sensors and effectors, and 270º projec-

tions. One of the applications and platforms developed with XIM is the persistent

virtual community (PVC), a system where the physical world is mapped into a vir-

tual world, and which is accessible both from XIM and remotely via a desktop

computer (see Section 18.3.1 below). In this way, the PVC is a venue where entities

of different degrees of virtuality (local users i n XIM, Avatars of remote users, fully

synthetic characters) can meet and interact. The PVC provides augmented reality in

that in XIM remote users are represented by a lit floor tile and augmented virtuality

through the representation of users in XIM as avatars in the virtual world. XIM, in

combination with the PVC, can be thus located simultaneously at both extremes of

the “virtuality continuum” [2], qualifying XIM as a mixed-reality system.

18.1.2 Why Build Such Spaces? Epistemological Rationale

One can trace back the origins of psychology as far as antiquity, with the origins of

modern, scientific psychology commonly located in the installation of the first psy-

chological laboratory by Wilhelm Wundt in 1879 [20]. Over the centuries, the view

of the nature of psychology has undergone substantial changes, and even current

psychologists differ among themselves about the appropriate definition of psychol-

ogy [21]. The common denominator of the different approaches to psychology –

biological, cognitive, psychoanalytical, and phenomenological – is to regard psy-

chology as the science of behavior and mental processes [20]. Or in Eysenck’s words

[21], “The majority believe psychology should be based on the s cientific study of

behavior, but that the conscious mind forms an important part of its subject matter.”

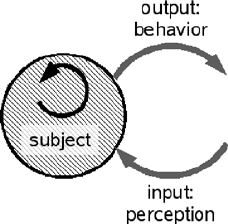

If psychology is defined as the scientific investigation of mental processes and

behavior, it is in the former case concerned with phenomena that are not directly

measurable (Fig. 18.3). These non-measurable phenomena are hence conceptual

entities and referred to as “constructs” [22]. Typical examples of psychological con-

structs are “intelligence” and the construct of the “Ego” by Freud [23]. Scientifically,

these constructs are defined by their measurement method, a step which is referred

to as operationalization.

Fig. 18.3 The field of

psychology is concerned with

behavior and mental

processes, which are not

directly measurable.

Scientific research in

psychology is to a large

extent based on drawing

conclusions from the

behavior a subject exhibits

given a certain input

362 U. Bernardet et al.

In psychological research humans are treated as a “black box,” i.e., knowledge

about the internal workings is acquired by drawing conclusions from the reaction to

a stimulus (Fig. 18.3; input: perception, output: behavior). Behavior is here defined

in a broad sense, and includes the categories of both directly and only indirectly

measurable behavior. The category of directly observable behavior comprises, on

the one hand, non-symbolic behavior such as posture, vocalization, and physiology

and, on the other hand, symbolic behavior such as gesture and verbal expression. In

the category of only indirectly measurable behavior fall the expressions of symbolic

behaviors like written text and non-symbolic behaviors such as a person’s history of

web browsing.

Observation: With the above definition of behavior, various study types such as

observational methods, questionnaires, interviews, case studies, and psychophysio-

logical measurements are within the realms of observation. Typically, observational

methods are categorized along the dimension of the type of environment in which

the observation takes place and the role of the observer. The different branches

of psychology, such as abnormal, developmental, behavioral, educational, clinical,

personality, cognitive, social, industrial/organizational, or biopsychology, have in

common that they are built on the observation of behavior.

Experimental research: The function of experimental research is to establish the

causal link between the stimulus given to and the reaction of a person. The common

nomenclature is to refer to the input to the subject as the independent variable, and

to the output as dependent variable. In physics, the variance in the dependent vari-

able is normally very small, and as a consequence, the input variable can be changed

gradually, while measuring the effect on the output variable. This allows one to test a

hypothesis that quantifies the relationship between independent and dependent vari-

ables. In psychology, the variance of the dependent variable is often rather large, and

it is therefore difficult to establish a quantification of the causal connection between

the two variables. The consequence is that most psychological experiments t ake the

form of comparing two conditions: The experimental condition, where the subject

is exposed to a “manipulation,” and the control condition, where the manipulation is

not applied. An experiment then allows one to draw a conclusion in the form of (a)

manipulation X has caused effect Y and (b) in the absence of manipulation X effect

Y was not observed. To conclude that the observed behavior (dependent variable)

is indeed caused by a given stimulus (independent variable) and not by other fac-

tors, so-called confounding variables, all conditions are kept as similar as possible

between the two conditions.

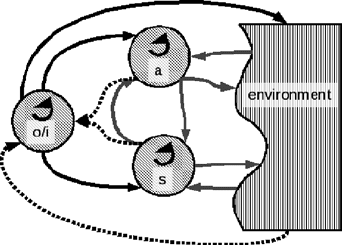

The concepts of observation and experiment discussed above can be captured

in a systemic view of interaction between the four actors: subject, social agent,

observer/investigator, and environment (Fig. 18.4). “Social agent” here means other

humans, or substitutes, which are not directly under investigation, but that interact

with the subject. Different research configurations are characterized by which actors

are present, what and how is manipulated and measured. What distinguishes the

branches of psychology is, on the one hand, the scope (individual – group), and, on

the other hand, the prevalent measurement method (qualitative–quantitative), e.g., in

a typical social psychology experimental research configuration, what is of interest

18 The eXperience Induction Machine 363

is the interaction of the subjective with multiple social agents. The subject is either

manipulated directly or via the persons he/she is interacting with.

Fig. 18.4 Systemic view of the configuration in psychological research. S: subject, A: social agent,

O/I: observer, or investigator (the implicit convention being that if the investigator is not perform-

ing any intentional manipulation, he/she is referred to as an “observer”). The subject is interacting

with social agents, the observer, and the environment. For the sake of simplicity only one subject,

social agent, and observer are depicted, but each of these can be multiple instances. In the dia-

gram arrows indicate the flow of information; more specifically, solid black lines indicate possible

manipulations, and dashed lines possible measurement points. The investigator can manipulate

the environment and the social agents of the subject, and record data from the subject’s behavior,

together with the behavior of other social agents, and the environment

The requirement of the experimental paradigm to keep all other than the indepen-

dent variable constant has as a consequence that experimental research effectively

only employs a subset of all possible configurations (Fig. 18.4): Experiments mostly

take place in artificial environments and the investigator plays a non-participating

role. This leads to one of the main points of critique of experiments, the limited

scope and the potentially low level of generalizability. It is important to keep in

mind that observation and experimental method are orthogonal to each other: In

every experiment, some type of observation is performed, but not in all observational

studies two or more conditions are compared in a systematic fashion.

18.1.3 Mixed and Virtual Reality as a Tool in Psychological

Research

Gaggioli [24] made the following observation on the usage of VR in experimental

psychology: “the opportunity offered by VR technology to create interactive three-

dimensional stimulus environments, within which all behavioral responses can be

recorded, offers experimental psychologists options that are not available using tra-

ditional techniques.” As laid out above, the key in psychological research is the

systematic investigation of the reaction of a person to a given input (Fig. 18.4).

364 U. Bernardet et al.

Consequently, a mixed-reality infrastructure is ideally suited for research in psy-

chology as it permits stimuli to be delivered in a very flexible, yet fully controlled

way, while recording a person’s behavior precisely.

Stimulus delivery: In a computer-generated environment, the flexibility of the

stimulus delivered is nearly infinite (at least the number of pixels on the screen).

This degree of flexibility can also be achieved in a natural environment but has to

be traded off against the level of control over the condition. In conventional experi-

mental research in psychology the environment therefore is mostly kept simple and

static, a limitation to which mixed-reality environments are not subject, as they do

not have to trade off richness with control. Clearly this is a major advantage which

allows research which should generalize better from the laboratory to the real-world

condition. The same r ationale as for the environment is applicable for social interac-

tion. Conventionally, the experimental investigation of social interaction is seen as

highly problematic, as the experimental condition is not well controlled: To investi-

gate social behavior, a human actor needs to be part of the experimental condition,

yet it is very difficult for humans to behave comparably under different conditions,

as would be required by experimental rigor. Contrary to this, a computer-generated

Avatar is a perfectly controllable actor that will always perform in the same way,

irrespective of fatigue, mood, or other subjective conditions. A good example of

the application of this paradigm is the re-staging of Milgram’s obedience experi-

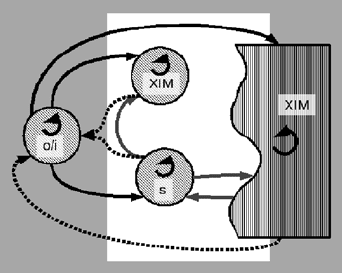

ment [25]. The eXperience Induction Machine can fulfill both roles; it can serve

as a mixed-reality environment and as the representation of a social agent (Fig.

18.5). Moreover the space can host more than a single participant, hence allowing

an expansion from the advantages of research in a mixed-reality paradigm to the

investigation of groups of subjects.

Recording of Behavior: To draw conclusions from the reaction of persons to a

given stimulus, the behavior, together with the stimulus, needs to be measured with

high fidelity. In XIM, t he spatio-temporal behavior of one or more persons can be

recorded together with the state of the environment and virtual social agents. A key

feature is that the tracking system is capable of preserving the identity of multiple

users over an extended period of time, even if the users exhibit a complex spatial

behavior, e.g., by frequently crossing their paths. To record, e.g., the facial expres-

sion of a user during an experiment in XIM, a video camera is directly connected to

the tracking system, t hus allowing a videorecording of the behavior to be made for

real-time or post hoc analysis. Additionally, XIM is equipped with the infrastruc-

ture to record standard physiological measures such as EEG, ECG, and GSR from a

single user

Autonomy of the environment: A unique feature of XIM is the usage of the large-

scale neuronal systems simulator iqr [1] as “operating system.” The usage of iqr

allows the deployment of neurobiological models of cognition and behavior, such

as the distributed adaptive control model [26] for the real-time information inte-

gration and control of the environment and Avatars (Fig. 18.5, spirals). A second

application of the autonomy of XIM is the testing of a psychological user model

in real time. Prerequisite is that the model is mathematically formulated as is, e.g.,

the “Zurich model of social motivation” [27]. In the real-time testing of a model,

18 The eXperience Induction Machine 365

Fig. 18.5 Systemic view of the role on the eXperience Induction Machine (XIM) in psychological

research. XIM is, on the one hand, a fully controllable dynamic environment and, on the other

hand, it can substitute social agents. Central to the concept of XIM is that in both roles, XIM has

its own internal dynamics (as symbolized by spirals). The shaded area demarcates the visibility as

perceived by the subject; while XIM is visible as social agent or as environment, the investigator

remains invisible to the subject

predictions about the user’s response to a given stimulus are derived from the model

and instantly tested. This allows the model to be tested and parameters estimated in

a very efficient way.

18.1.4 Challenges of Using Mixed and Virtual Realities

in Psychological Research

As in other experimental settings, one of the main issues of research using VR and

MR technology is the generalizability of the results. A high degree of ecological

validity, i.e., the extent to which the setting of a study is approximating the real-life

situation under investigation, is not a guarantee, but a facilitator for a high degree of

generalizability of the results obtained in a study. Presence is commonly defined as

the subjective sense of “being there” in a scene depicted by a medium [28]. Since

presence is bound to subjective experience, it is closely related to consciousness, a

phenomenon which is inherently very difficult, if not even impossible, to account for

by the objective methods of (reductionist) science [29]. Several approaches are pur-

sued to tackle the presence. One avenue is to investigate determinants of presence.

In [30] four determinants of presence are identified: The extent of fidelity of sen-

sory information, sensory–motor contingencies, i.e., the match between the sensors

and the display, content factors such as characteristics of object, actors, and events

represented by the medium, and user characteristics. Alternatively, an operational

definition can be given as in [31], where presence is located along the two dimen-

sions of “place illusion,” i.e., of being in a different place than the physical location,

and the plausibility of the environment and the interactions, as determined by the

plausibility of the user’s behavior. Or, one can analyze the self-report of users when