Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Another useful literary extract which details something of the structure of

small towns in the mid-nineteenth century is to be found in Thomas Hardy’s

Mayor of Casterbridge. ‘Casterbridge’ (based on Dorchester) in the s was

deposited in a block upon a cornfield. There was no suburb in the modern sense,

or transitional intermixture between town and down. It stood, with regard to the

wide fertile land adjoining, clean-cut and distinct like a chessboard on a green table

cloth. The farmer’s boy could sit under his barley mow and pitch a stone into the

office window of the town clerk; reapers at work among the sheaves nodded to

acquaintances on the pavement corner; the red-robed judge, when he condemned

a sheep stealer, pronounced sentence to the tune of Baa that floated in at the

window from the remainder of the flock browsing hard by; and at executions, the

waiting crowd stood in the meadow immediately before the drop, out of which

the cows had been temporarily driven to give the spectators room.

39

This highlights the compact nature of most small towns at mid-century.

Within this small space, however, there were considerable social gulfs to be

found. Neil Wright describes the social geography of Lincolnshire towns suc-

cinctly and his statement is of general applicability: ‘In there were still many

people living in the centre of towns – tradesmen or shopkeepers living over their

premises and working people in courtyards and lanes behind them.’

40

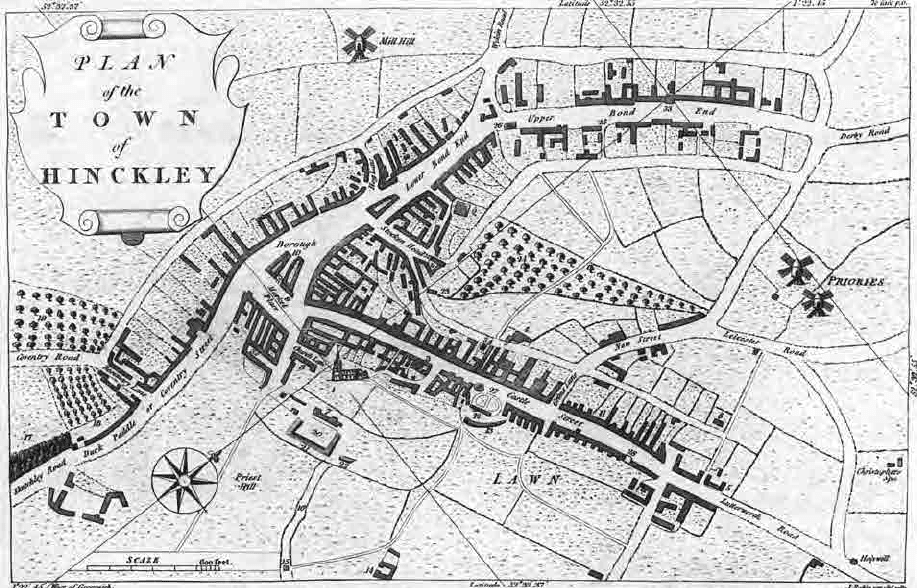

Early

industrialisation reinforced rather than rearranged this pattern. Towns like

Bromsgrove and Hinckley located their domestic or workshop industries behind

the main streets. In Hinckley the framework knitters mostly resided in terraces

or lean-to dwellings in the yards of the inns and farmhouses that had fronted the

main streets of the old market town. As their number increased and proper access

became necessary, the former farm lanes behind the yards were paved, giving

Hinckley a system of parallel streets in its centre, apparent even from the late

eighteenth century (Map .). The wealthier people at mid-century still lived

on the main streets, some of them in buildings that doubled as shops or other

commercial premises.

Change, however, was imminent both to the internal geography of the small

towns and to their distribution and function:

‘Casterbridge’ in was doubtless an odorous town ruled by a brutal code of

law in which the desperately poor lived in the shadow of the immoderately rich.

But as a town it was still an organic whole . . . an identifiable unit that was greater

than the sum of its parts. It would see more change, qualitatively, in the next

hundred years than it had in the previous thousand.

41

In non-fictional Lerwick: ‘soon houses would be appearing in the area between

Hillhead and Burgh Road [the New Town], gas would illuminate the streets and

Stephen A. Royle

39

T. Hardy, The Life and Death of the Mayor of Casterbridge,a Story of a Man of Character (London, ),

p. .

40

N. R. Wright, LincolnshireTowns and Industry, – (Lincoln, ), p. .

41

R. Chamberlin, The English Country Town (Exeter, ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Map . Hinckley, Leicestershire,

Source: J. Nichols, The History and Antiquities of Hinckley (London, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

lanes and tap water was not all that far away. Lerwick was on its way.’

42

For

Scotland generally ‘the future development of towns lay in the complex and

ever-changing interplay of sources of raw materials, markets, labour supply and

transport: the industrial town was about to come into being’.

43

(ii)

The census estimated that the urban percentage of the population of

England and Wales rose from . to from to . The overall spatial

pattern of this urban growth was identified by Brian Robson thus: ‘the growth

of industrial production [and associated urban development] was focused on the

mineral bearing and carboniferous areas of “Highland Britain”’.

44

This was

somewhat anomalous in British urban history where hitherto urban growth had

been in the overwhelmingly dominant London and the South-East of England

– lowland Britain. (For much of the twentieth century the pattern of urban

growth in lowland Britain reasserted itself.)

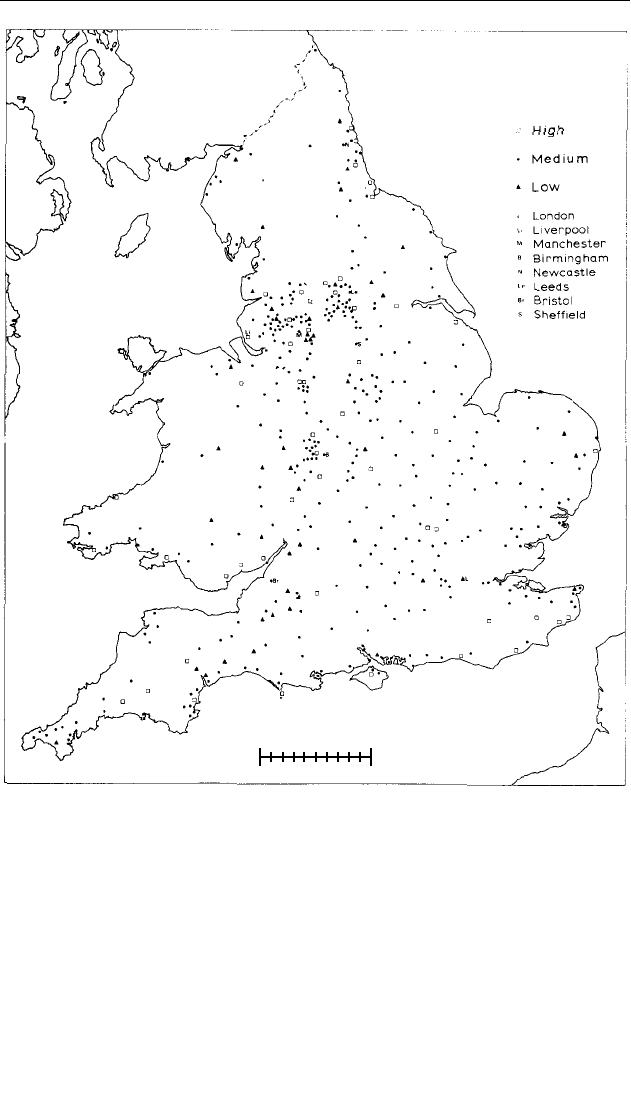

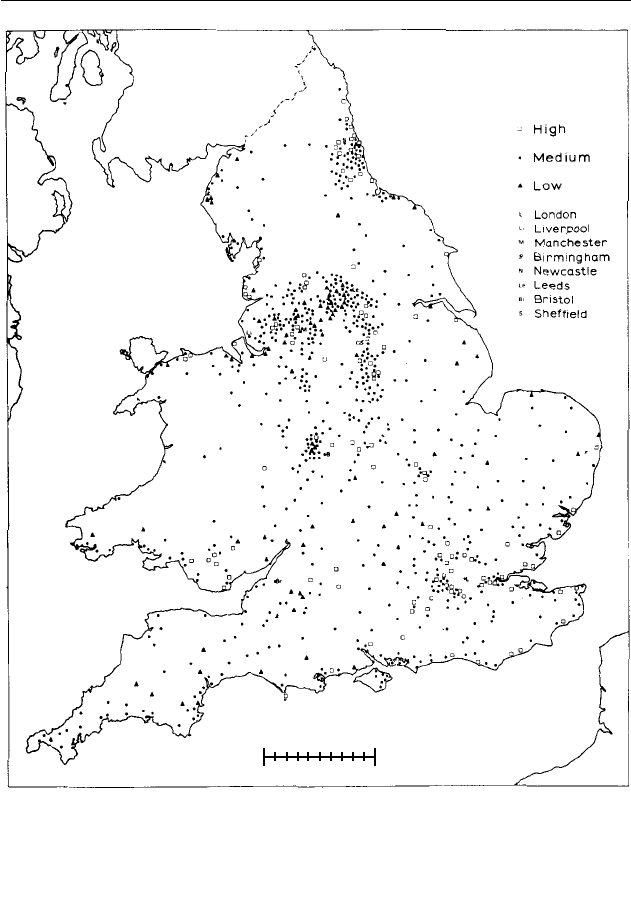

Maps . and . are taken from Robson’s analysis. The former presents the

urban pattern (of places above ,) of England and Wales at with details

of rates of growth in the previous decade. The latter does the same for

when the imposition of Victorian industrial and urban growth in the mining and

manufacturing regions upon the pre-existing, more evenly distributed urban

network is clear. In , in addition, the suburbanisation around London stands

out and the growth of seaside resorts can also be identified.

Buried within these overall analyses was the development of the small-town

sector. Robson’s smallest category of town, from ,–,, though increas-

ing in numbers – in , in – became proportionately less impor-

tant, falling from . per cent of the total urban places in to . per cent

in . N. Raven stated that ‘“small towns” shared the fortunes of nineteenth

century rural England, experiencing demographic growth and economic expan-

sion up to c. but subsequently suffering from decay in crafts and local indus-

tries with the resultant depopulation’.

45

Richard Lawton, too, linked the

agricultural areas and the old market towns and showed that there was a general

decrease in population of such areas after because of the concentration of

industrial employment, greater mobility brought about by railway development

and a relative decline of countryside employment.

46

On decline, Christopher

Stephen A. Royle

42

Irvine, Lerwick, p. .

43

Adams, Urban Scotland, p. .

44

B. T. Robson, Urban Growth (London, ), p. .

45

N. Raven, ‘Occupational structures of three north Essex towns: Halstead, Braintree and Great

Coggeshall, c. –. Research in progress’, Urban History Newsletter, (), .

46

R. Lawton, ‘Population changes in England and Wales in the later nineteenth century: an anal-

ysis of trends by registration districts’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, (),

–.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Law identified urban places which between and did not experience

major urban growth (less than per cent).

47

If this map is compared to a map

of urban centres in , it can be seen that outside London and the Home

Counties, and the industrial areas, a large proportion of urban settlements come

into this category. In the main they are either market centres (not the lowest

grade since most of these have already been excluded by the imposition of a

The development of small towns in Britain

47

C. M. Law, ‘The growth of urban population in England and Wales, –’, Transactions of

the Institute of British Geographers, (), –.

Map . Urban distribution and growth –, England and Wales

Source: B. T. Robson, Urban Growth (London, ).

0 kilometres 100

0 miles 62

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

threshold of ,) or decayed ports such as Chepstow, Chichester or Lynn

which lost trade with the coming of the railways.

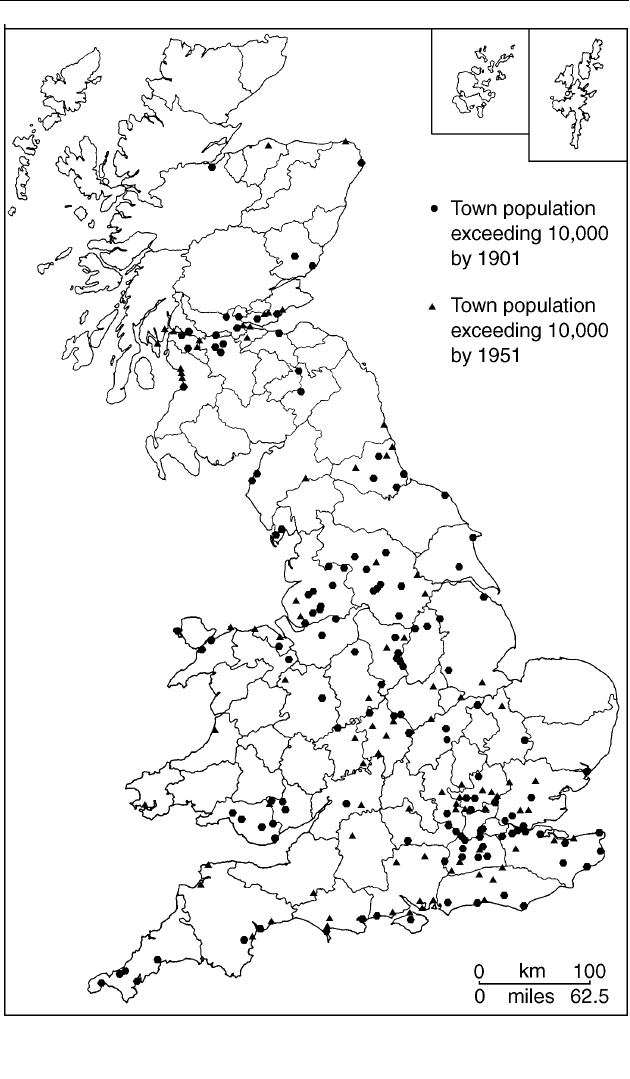

More successful were the of the original small towns of and

which reached , before . They are located on Map . and most were

either industrial or, alternatively, suburban areas around London, though some

were market towns which had grown and prospered by having ‘demonstrated an

imperial tendency to annex the trade [of other market towns] by virtue of

Stephen A. Royle

Map . Urban distribution and growth –, England and Wales

Source: B. T. Robson, Urban Growth (London, ).

0 kilometres 100

0 miles 62

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

railway connections and superior shopping facilities’.

48

In situations where most

towns had a railway connection, however, the comparative advantage a link pro-

vided was neutralised. This was the situation in southern Shropshire where it was

the smaller towns that benefited most from railways, increasing their range of

functions more quickly than the two larger regional centres of Bridgnorth and

Ludlow, both of which lost population from to (⫺. per cent and

⫺ per cent respectively). Transport developments per se were another factor that

had led to the growth of some of these towns, such as Swindon, a railway

town whose population of , almost doubled to , by .

In Scotland more small towns expanded with more than per cent increas-

ing their population between and . In Scotland they clearly fall into

two categories: the rural counties such as Caithness and Inverness and the smaller

industrial counties of the Central Valley where small-town growth was associated

with industrialisation. There was some suburban growth in central Scotland, too.

Helensburgh (which increased per cent from to ) and North

Berwick ( per cent) were ‘pleasantly situated towns [which] evolved as resi-

dential retreats for the cities because the railways made it possible’.

49

Wales had

a similar experience to Scotland in that rural counties like Merionethshire and

Radnorshire stood out as did industrial counties such as Flintshire and

Glamorgan. Carter specifically separated the ‘market principle’ which he saw as

the factor which best explained the distribution of Welsh towns in an earlier

period from the ‘“industrial principle” whereby the controls of town location

are the same factors which determined the location of mining and industry’.

50

Thus, regarding Caerphilly, ‘no settlement of any significance had grown around

the huge castle [but it] quickly became a mining town of considerable impor-

tance and entered the upper ranks of the urban hierarchy [a population increase

of ,. per cent from to ]’.

51

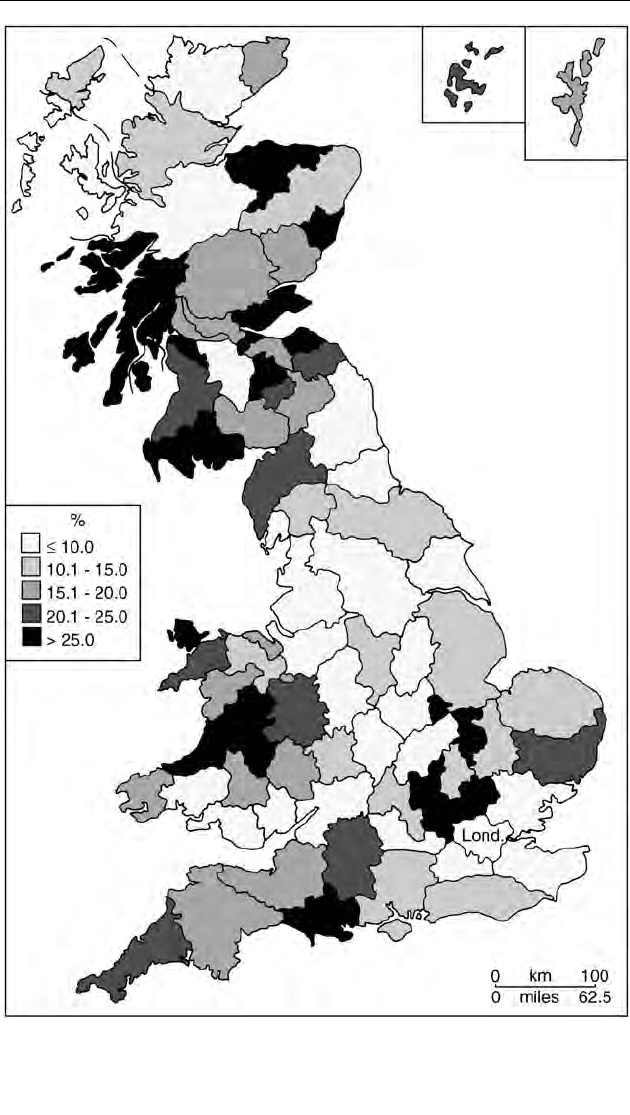

England, with more of its urbanisation in cities, had fewer counties showing

sustained growth in small towns. Some rural counties such as Rutland stood out

in (Map .) and in England there was another category of county whose

small towns had grown – those like Surrey close to London which became

enmeshed in metropolitan development – ‘the modern world . . . submerging

it’.

52

All fifteen of Surrey’s small towns increased in population from to

, some to become substantial urban places such as Kingston-upon-Thames,

Richmond and Reigate.

Accessibility was an important factor in explaining growth. Less accessible

country towns and their tributary areas continued to lose population with del-

eterious effects upon their economies. Within a framework of agricultural

The development of small towns in Britain

48

Waller, Town,p..

49

R. J. Naismith, The Story of Scotland’sTowns (Edinburgh, ), p. .

50

Carter, The Towns of Wales, pp. –.

51

Ibid., p. .

52

G. Bourne (pseudonym of G. Sturt), Change in the Village (London, ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Stephen A. Royle

Map . British small towns reaching , residents by and

Source: based on census data.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The development of small towns in Britain

Map . Proportion of county populations living in small towns in Great

Britain

Source: based on census data.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

depression which hastened the decline of some Lincolnshire towns where only

twelve of thirty-two in the cohort increased in population between and

, Wright asserted that the fine detail within this pattern was related to

accessibility, with those towns with a railway station faring better.

53

In Market

Harborough the opening of the railway in had led to the local tradesmen

considering how this increased accessibility could benefit the town. The result

was the new Corn Exchange.

54

Map . identifies the relative importance of the small towns within their

county’s population and the national decline from . per cent to per cent

from to is reflected in the increase in counties in the lowest category,

with the industrial counties being joined by some of the Home Counties where

many towns had grown beyond the , threshold. Many towns in the cohort

remaining under , were traditional market towns that had failed to take on

new industries. Others were manufacturing towns whose industry had not pros-

pered in the new era.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, localism which had been the

principal characteristic of the traditional market town for centuries, began to

decay. ‘The intimacy of the small market town suffered invasions, and the local

provision of services was encroached upon.’

55

Further, the growth of govern-

ment regulation and the increase of national legislation ‘tipped the scales against

the self-sufficiency and individuality of country town life’.

56

Especially

significant was the way in which the traditional country town became little more

than the agent for city or big firm interests as long-standing local industries col-

lapsed in the face of competition from major capitalist concerns. Philip Waller

exemplifies such developments in milling and brewing. Milling had been a

locally based activity which in employed , people, mainly in small

facilities in or just outside country towns. Fifty years on the development of cap-

italism had seen the growth of large vertically integrated regional, even national,

companies dealing with not just milling but also seed crushing, animal feed pro-

duction and the marketing of end products. These big firms took advantage of

the increased importation of grain by erecting huge mills at the ports. New mills

employed modern roller grinding techniques which were more efficient than

the old mill-stones but to establish a factory using them required major invest-

ment beyond the reach of local, traditional millers. Transportation improvements

permitted even bulky products like grain to be moved fairly readily and so the

big mills could take in grain from a large area. All these developments combined

to see the decline of the local miller, unable to compete. ‘By the market

was effectively dominated by actual or emerging giants, Joseph Rank, Spillers,

Bibby, Thorley, Silcock, the CWS [Co-operative Wholesale Society] and

Stephen A. Royle

53

Wright, Lincolnshire Towns.

54

J. C. Davies and M. C. Brown, Yesterday’s Town (Buckingham, ).

55

Waller, Town, p. .

56

Ibid., p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

BOCM [British Oil and Cake Mills Ltd]. Bibby’s alone, for instance, employed

people in Liverpool by , , in .’

57

With regard to brewing a similar pattern emerged. In Waller estimated

that there were , breweries and , private brewers; by just ,

and , respectively. The decimation of the private brewers is especially

significant here for these were likely to have been small-scale local operations

characteristic of the market towns. Small towns with an industrial element to

their economies thus had to invest or see their economies suffer. In Hinckley,

though, there was another depression in the s when the American Civil War

cut off the cotton supply. The town’s entrepreneurs finally modernised its pro-

duction facilities from domestic frames into proper factories and were rewarded

by Hinckley’s population having increased per cent between and .

By contrast, manufacturing towns whose industry was not modernised declined.

Dickinson singled out old Norfolk woollen towns such as Diss and Kenninghall

and Coggeshall in Essex where there was ‘a rapid decline in the formerly pros-

perous crafts and small industries’.

58

Coggeshall’s population declined per cent

between and .

A diverse economy could also be helpful. Melton Mowbray, with food pro-

cessing and fox-hunting supporting its central-place functions, saw its popula-

tion rise . per cent. Nearby, Lutterworth, a more traditional agricultural

service town which did not change much, experienced a population fall of

per cent. Further down the hierarchy some places fared worse, including Market

Bosworth which declined . per cent. Dickinson pointed out the lack of func-

tional diversification of East Anglian towns which failed to grow such as

Swaffham, Norfolk (⫺. per cent), and the Suffolk towns of Bungay (⫺.

per cent), Eye (⫺. per cent) and Woodbridge (⫺. per cent). These were

amongst those towns where functions such as livestock markets and/or corn fac-

toring declined in face of larger-scale, more accessible facilities elsewhere.

59

Thus, it is clear that by the end of the nineteenth century, if a small town

could not adapt to change it faced decline. Marlborough had a population fall

of per cent from to , despite the success of its college founded in

, for ‘it remained as it had been, the capital of an agricultural kingdom’,

without ‘new industries’.

60

The detail of life in the small towns of late Victorian Britain continued to

depend upon the type of town it was. Thus regarding the small towns of Surrey,

enmeshed in the growth of the metropolis, George Bourne catalogued, with

regret, the change this ‘invasion of a new people, unsympathetic to [the old]

order’ wrought to customary traditions and mores. ‘As he [Bourne’s labourer]

sweats at his gardening, the sounds of piano playing come to him, or of the

affected excitement of a tennis party; or the braying of a motor car informs him

The development of small towns in Britain

57

Ibid., p. .

58

Raven, ‘Essex towns’, .

59

Dickinson, ‘East Anglia’.

60

Waller, Town, p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008