Danver Steven L. (Edited). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Methodist Church, the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, and the

National Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs. Members of

these groups promoted greater opportunities for women a nd had been doing so

for decades. They focused much of their attention outside of the traditional politi-

cal arena in an era when women were effectively barred from positions of power

within politics. By doing so, they paved the ground for the rise of the second wom-

en’s movement in the 1960s. Feminism did not crest out of nowhere.

Before Friedan sat down at her typewriter, the women in these organizations

articulated the reasons for th eir dissatisfaction and formulated plans to do some-

thing about the second-class status of women. The ANA, founded in 1896, viewed

itself as a labor organization and not a women’s group. It sought to better the

working conditions and pay accorded to nurses. In the 20th century, the nursing

profession happened to consist almost entirely of women. The ANA discovered

that it had to boost the st atus of women before it could boost working conditions

and pay for women worker s. It began to work along these lines in the 1940s and

1950s. The AAUW, begun in 1881, focused on educating women and helping

women to make use of their education. To fight against the perception that

women’s brains w ere second-rate, the AAUW had to better the social position

of women. AKA, an African American sorority founded in 1909, fought sexism

to uplift the race with the members realizing that men alone could not effect

change. (Women in African American sororities continue to remain highly active

in the organizations long after college graduation, unlike their white counterparts.

Black sororities have long been part of the movements for social and political

equality.) CWU, established in 1941, objected to women being only the spine of

the church. They wanted to be the brain as well. Women raised much of the money

to support the church, and women wanted a say in how the church operated. For all

of these g roups , the second-class status of women interfered with their ability to

achieve their narrowly focused goals. By necessity, they embraced feminism.

Achievements of Feminism

Liberal and traditional feminists promoted the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) as

well as equal pay. They succeeded with the latter but failed spectacularly with the

former. In 1945, feminists introduced a bill to protect women’s pay, but the mea-

sure gathered little support until the formation of President John F. Kennedy’s

Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) in 1963. Pushed by Esther Peterson,

head of the Women’s Bureau of the Department of Labor, the CSW agreed that

fairness demanded equal pay, and it endorsed the concept. Debate soon arose over

whether equal pay meant that all w orkers at a particular job or a part icular level

would receive the same wages. Employers opposed the bill, and members of

Congress voiced fears that equal pay would take jobs away from men, but

1048 Feminist Movement (1970s–1980s)

opponents surrendered when they became convinced that the bill would be more

symbolic than effective because of widespread job segregation by sex. The Equal

Pay Act provides that employers may not pay workers of one sex at rates lower

than they pay employees of the opposite sex employed in the same establishment

for equal work. It applies to jobs that require sub stantially equal skill, effort, and

responsibility and that are performed under similar working conditions. Excep-

tions to the law are permitted when sex difference s in pay are due to s eniority,

merit, quantity or quality of production, or any factor other than sex. In 1972,

the provisions of the law were extended to management and professional employ-

ees as well as to state and local government workers. Employers with fewer than

25 employees remain exempt.

The NWP stru ggled to get other women’s organizat ion to promote the ERA in

the years since its 1923 creation. They refused to do so for fear that the legislation

would wipe out protective labor laws that helped women. When Congress debated

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the NWP persuaded Democratic representative

Howard Smith of Virginia to sponsor an amendment adding “sex” to Title VII,

the section prohibiting discrimination in employment. Smith, a conservative and

no friend o f progressive legislation, may have inte nded the amendment as a joke

that would emphasize the silliness of civil rights a nd kill the bi ll. However, the

act passed into law along with Title VII. Protective labor laws, which typically

prohibited women from holding certain jobs and working nights, were abolished

by the legislation.

With the issue of protective legislation now moot, many women’s organizations

came to support the ERA. NOW endorsed the amendment in 1967 and took the

leadership of the ERA fight from the nearly extinct NWP. On March 22, 1972,

the Senate approved the ERA by a vote of 84 to 8, and it was sent to the states.

Six states ratified the amendment within two days, and by the middle of 1973,

the amendment seemed well on its way to adoption with 30 of the needed 38 states

having ratified. The debate over the ERA cha nged when passage appeared immi-

nent as conservatives and religious fundamentalists launched a grassroots cam-

paign aimed at all things deemed to be unnatural and immoral. Phyllis Schafly,

founder of Stop ERA, portrayed the amendment as a threat to family values and

traditional relationships between men and women. She saw women not as equals

to men, but as a gendered class that enjoyed certain protections and differential

treatment. When it seemed apparent that the ERA would not meet the 1979 dead-

line for ratification, supporters gained an extension from Congress until June 30,

1982. No other propo sed amendment has ever received an extensi on. The excep-

tion did not help the ERA, and it died. The loss reflected the new cha llenges that

faced feminism, specifically the rise of the New Right. Feminists moved on to

other issues, such as reproductive rights.

Feminist Movement (1970s–1980s) 1049

The Third Wave

In the 1980s, the feminist movement shifted into the third wave as the daughters of

second-wave activists came of age. Also identified as part of the post-feminist era,

these women were more moderate than many of the second-wave activists and

wary of being perceived as man-hating lesbians. They were prone to making state-

ments such as, “I’m not a feminist but ...” The third wave grew up with the

advances achieved by the second wave. They were accustomed to women in the

workforce, had always enjoyed equal educ ational opportunities, and took for

granted that they were the equals of men. They supported gender equality, planned

to work after marriage, and expected men to play an equal part in family life.

Many did not see the need for a movement and could not see a commonality with

other women. The third wave of feminism lacked a clear identity. It tended to

focus on narrow issues, such as date rape and sexual harassment th rough such

grassroots organizations as Take Back the Night marches.

Conclusion

Feminists of the second wave wanted a movement that embraced them and

changed the world. When change did not occur—now—many felt betrayed. Fem-

inists of all stripes were likely to turn on one another because of the damage they

had experienced in th e larger society and the disappointment that they felt when

they discovered that feminism was not going to make their lives as decent or ful-

filled as they had hoped. Women often could not live up to the high expectations

that feminism encouraged. The entrance of women into the workforce also left

many women with less time for act ivism. By the 1980s, many feminists dropped

out of feminist organizations and either abandoned efforts to effect social change

or joined groups that focused on narrow concerns such as reproductive freedom.

—Caryn E. Neumann

See also all entries under Women’s Movement (1870s); Civil Rights Movement (1953–1968).

Further Reading

Castro, Ginette. Americ an Feminism: A Contemporary History. New York: New York Uni-

versity Press, 1990.

Echols, Alice. Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in Americ a, 1967–1975. Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press, 1989.

Evans, Sara. The Roots of Women’s Liberation in the Civil Rights Movement and the New

Left. New York: Vantage, 1980.

Flammang, Janet A. Wom en’s Political Voice. Philadelphia: Temple University Press,

1997.

1050 Feminist Movement (1970s–1980s)

Freedman, Estelle B. No Turning Back: The History of Feminism and the F uture of

Women. New York: Ballantine Books, 2002.

Hartmann, Susan M. From Margin to Mainstream: American Women and Politics since

1960. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989.

Henold, Mary J. Catholic and Feminist: The Surprising History of the American Catholic

Feminist Movement. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Hennessee, Judith. Betty Friedan: Her Life. New York: Random House, 1999.

Horowitz, Daniel. Betty Friedan and the Making of The Feminine Mystique. Amherst:

University of Massachusetts Press, 1998.

Levine, Susan. Degrees of Equality: The American Association of Universi ty Women and

the Challenge of Twentieth-Century Feminism. Philadelphia: Temple University Press,

1995.

Rosen, Ruth. The World S plit O pen: How the Modern Women’s M ovement Ch anged

America. New York: Viking, 2000.

Feminist Movement (1970s–1980s) 1051

Equal Rights Amendment (ERA)

The Equal Rights A mendment, popularly known as the ERA, sought to declare

unconstitutional all laws that discriminated against women. But stiff opposi tion

to the proposal, some of it coming from women themselves, undermined the effort.

The idea for an Equal Rights Amendment had its o rigins in the 19th century.

Susan B. Anthony and Lucretia Mott convened a women’s conference in 1848

at Seneca Falls, New York. They issued a declaration calling for equal rights

and the right to vote. But neither Anthony nor Mott lived to see either idea enacted

into law.

The 20th century saw a renewed effort by women to win the vote, propelled by

two organizati ons; the National American Woman Suffrage Association, and the

National Woman’s Party, led by Alice Paul. It was Paul’s movement that seeme d

to have the most influence over politicians, and by 1920 Congress and t he states

had agreed on the Nineteenth Amendment, giving women the right to vote.

Not content with simple voting rights, Paul and the National Woman’s Party

went one step further. In 1923, she proposed an Equal Rights Amendment, which

said that men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and

1053

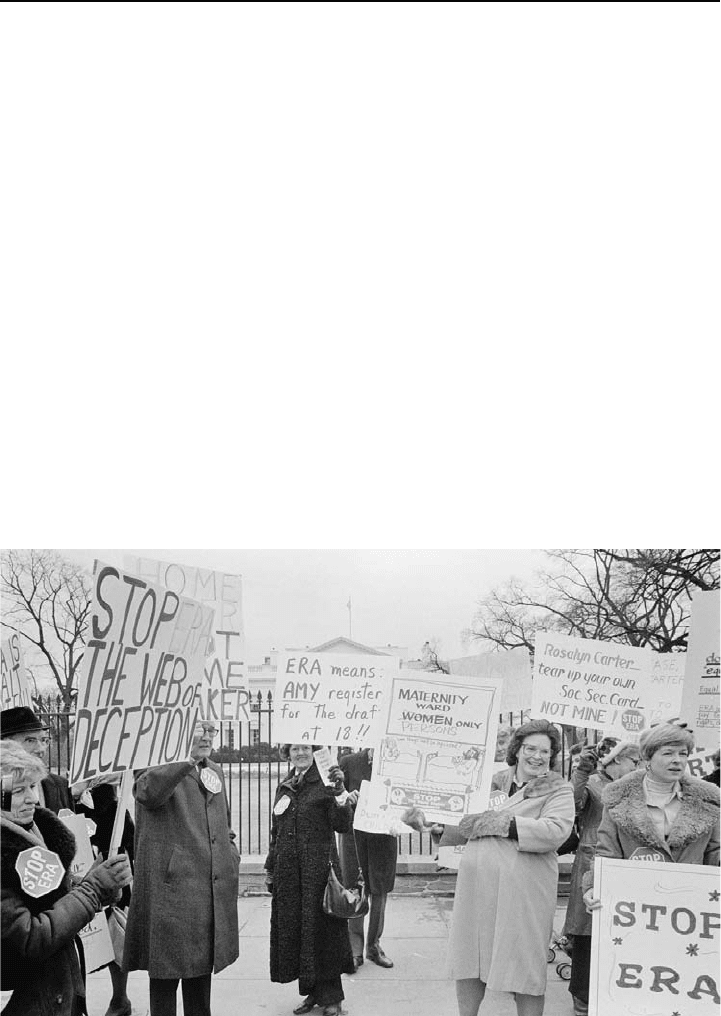

Women hold signs protesting against the ratification of the federal Equal Rights Amendment

outside the White House, February 1977. (Library of Congress)

every place subject to its jurisdiction. The idea stalled, however, blocked in part by

some women who feared passage of such an amendment would undo labor laws

that had protected women from exploitive treatment. During World War II, Paul

rewrote the amendm ent to provide that equality of rights under the law shall not

be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex. But

progress remained st ymied by labor leaders still inte nt on a double sta ndard in

the workplace and by social conservatives who perceived equal rights for women

as a threat to the status quo.

The decade of the 1960s, with its emphasis on civil rights for African Ameri-

cans, proved to be the right climate for women to once again take up the cause

of equal rights on their own behalf. Tying their fortunes with the civil rights move-

ment, and now joined finally by organized labor, they posed a formidable coalition

that convinced politicians that now was the time to act. The Equal Rights Amend-

ment cleared the Congress in 1972, and headed out to the states for ratification. It

was immediately ratified by 22 of the necessary 38 states. But over the next three

years, only 12 states fell into line.

1054 Feminist Movement (1970s–1980s)

’

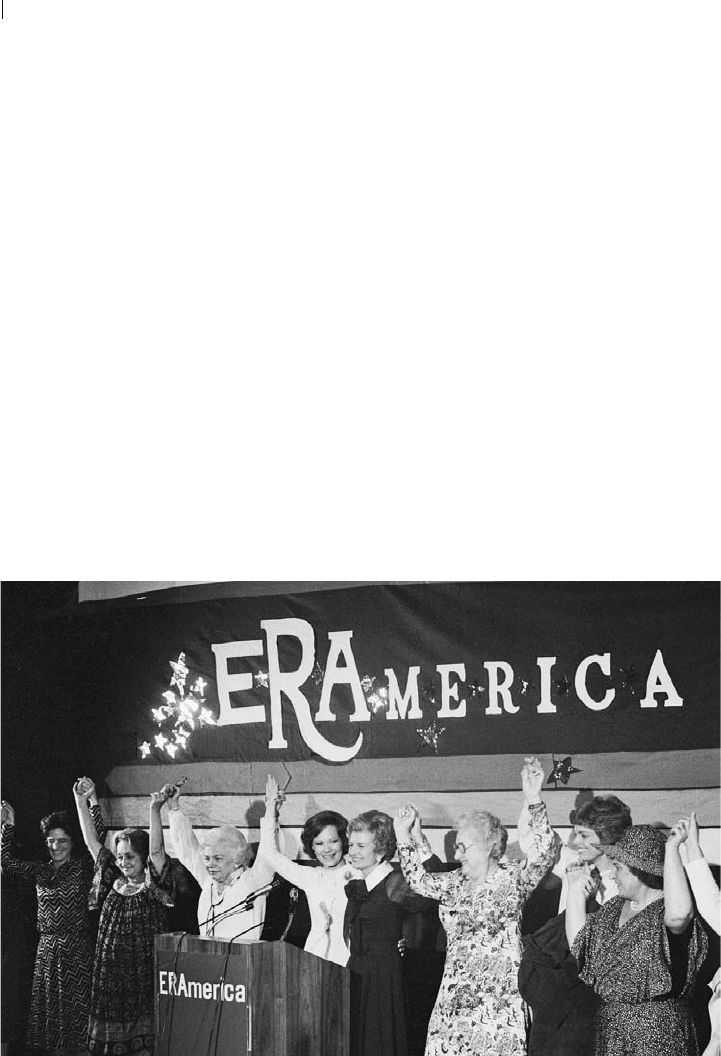

Rosalynn Carter and Betty Ford at the National Women's Conference in Houston on

November 19, 1977. The event is considered by many historians to be a milestone in the

feminist movement. The bipartisan attendance at the conference, and the presence of

women like Carter and Ford, lent credibility to the movement. With such mainstream support,

it became less of a stigma to be considered a feminist. (Bettmann/Corbis)

Opposition to the ERA came from all sides. Some women c laimed it would

eliminate their right to be supported by their husbands, and might even expos e

them to combat. Social conservatives argued the ERA would serve to strength en

abortion laws and efforts to legalize homosexual and lesbian activities. Critics of

big government warned that the federal government would use the ERA to extend

its power over the states. In spite of the opposition, ERA supporters managed to

put Indiana into the “yes” column in 1977, bringing the number of states support-

ing ratification to 35. But the amendment was still three states short, and despite an

extension, which lengthened the customary time period from seven to 10 years, the

ERA remained stalled at 35 when time expired on June 30, 1982. It remains to this

day unfinished business.

—John Morello

Further Reading

Huckabee, David. Equal Rights Amendme nt: Ratification Issues. Washington, DC:

Congressional Research Service, 1996.

Mansbridge, Jane. Why We Lost the ERA. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.

Roe v. Wade (1973)

Roe v. Wade was a case heard by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of a

woman’s right to an abortion. The decision was a major development in the

feminist movement, as it sign aled the right of women to exercise more personal

freedom, and to have that freedom protected by law.

The case began in 1970, when Norma McCorvey, a woman in Texas who

claimed she had been raped, sought an abortion. At the time, abortion was illegal

in Texas, but McCorvey was seeking an injunction, or an exemption to the statute.

Although a U.S. district court in Texas sympathized with her plight, it refused to

set aside the law. The case arrived before the Supreme Court on appeal in Octo-

ber 1972, with McCorvey, now only identified as Jane Roe, as the plaintiff, suing

Henry Wade, the district attorney of Dallas County, as the defendant. Lawyers

for the state of Texas argued that the state law banning abortion was clear, and

what McCorvey was asking for w as illegal, w hile lawyers for McCorvey argued

that it was a woman’s right to terminate a pregnancy at any time of her choosing.

The Supreme Court’s decision would be a repudiation of Texas law, yet a limited

victory for women’s rights.

Voting 7–2 and handing down its decision in January 1973, the Supreme Court

sided with McCorvey. Justice Harry Blackmun wrote the majority opinion, while

Feminist Movement (1970s–1980s) 1055

Justice Byron White and Chief Justice Warren Burger issued the dissenting

opinion. Speaking for the majority, Blackmun argued that most antiabortion laws

violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which provided, among

other things, equal protection under the law, the right to due process, and the right

to privacy. The ruling overturned state and federal antiabortion laws. However, the

Court repudiated c laims b y w omen that they were entitled to an abortion at any

time during pregnancy, holding that once the fetus reached a stage of viability,

anywhere between 24 and 28 weeks, an abortion could b e conducted o nly if the

mother’s health was in jeopardy.

Roe v. Wade has been hailed by many women as a red letter day for the feminist

movement, as it established the right of women to exercise more personal freedom

and guaranteed that freedom would be protected by the federal government. It also

angered those who argued the Supreme Court overstepped its bounds by legislat-

ing from the bench and weighing in on social issues that were none of its business.

Still, more than 30 years on, Roe v. Wade remains a landmark decision.

—John Morello

Further Reading

Garrow, David. Liberty and Sexuality: The Right to Privacy and the M aking of Roe v.

Wade. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Weddington, Sarah. A Question of Choice. New York: Putnam, 1992.

Steinem, Gloria (1934–)

Gloria Steinem, a journalist, is one of the most prominent leaders of the women’s

liberation movement. In 1971, she founded and served as the first editor of Ms.

magazine, a publication that helped t o popularize feminism by reaching women

who would not have picked up a movement newsletter or newspaper.

Steinem came to feminism a bit later than many of her movement peers. Born in

Toledo, Ohio, on March 25, 1934, to Leo Steinem and Ruth Nuneville Steinem,

she is the granddaughter of Pauline Steinem. Steinem earned a BA from Smith

College in 1956 and then accepted a fellowship to India partly to evade her fiance

´

.

Returning to the United States, she became a journalist and gained considerable

notice for going undercover as Bunny Marie in a 1963 expose

´

of the Playboy

Clubs. Steinem spent the 1960s opposing the Vietnam War, supporting the United

Farm Workers, an d working a s a contributing editor to Glamour magazine. In

1969, as a political columnist for New York magazine, she attended a New York

City abortion s peak-out organized by the Redstockings. The experience proved

1056 Feminist Movement (1970s–1980s)

to be awakening. Steinem later related that a light bulb clicked on, and she realized

that she was a feminist. The experiences of losing assignments to less-experienced

male colleagues, the jokes about frigid wives and dumb blondes, and all the other

humiliations associate d with being a woman suddenly made sense. She realized

that she was not alone.

Other writers, including Jimmy Breslin and Tom Wolfe, warned Steinem that

taking up the cudgel for women’s rights would compromise her reput ation and

handicap her career. She ignored them to devote the remainder of her life to writ-

ing, lecturing, and campaigning for women’s rights. After founding Ms. magazine,

Steinem spent nearly two decades as its editor before stepping down in 1987 to

serve as contributing editor. Steinem cofounded the National Women’s Political

Caucus in 1971 and cofounded the Ms. Foun dation for Women in 1972. Steinem

spent 30 years on the board of the Women’s Action Alliance (now the Feminist

Majority Fund) with the aim of electing women to political office. Active in the

pro-choice movement since 1969, she served several terms as president of Voters

for Choice after her initial 1979 election.

The media appointed Steinem as a leader of the feminist movement in the early

1970s, though less photogenic women, such as Betty Friedan, had stronger femi-

nist credentials. Steinem did have a flair for turning a phrase, famously noting that

Feminist Movement (1970s–1980s) 1057

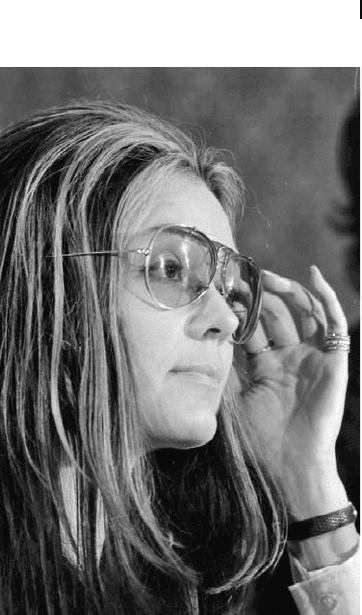

Gloria Steinem (1934) is an American

feminist, journalist, and spokeswoman

for women's rights. She founded Ms.

magazine in 1972 when this photo was

taken. (Library of Congress)