Cutle, Timothy: On Voice Exchange

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

201

Timothy Cutler On Voice Exchanges

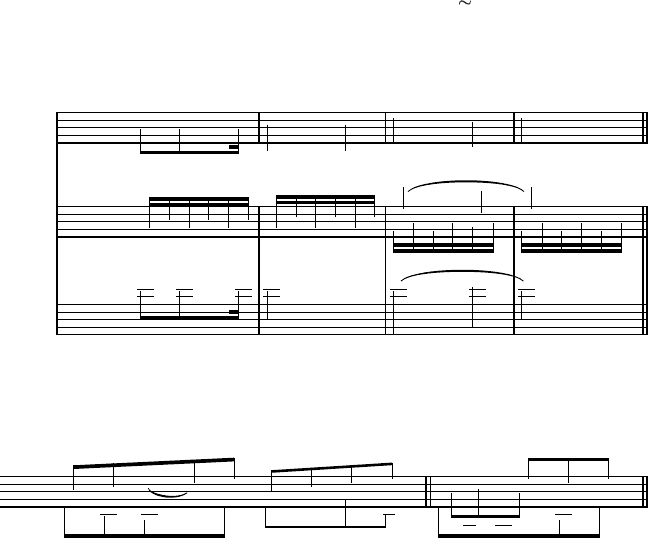

octaves on consecutive beats. Another option would be a bass descent from 4

ˆ

to 3

ˆ

, creating the “first-inversion” inverted V

6

4

, but the soloist descends from G

to F over the barline, and again parallels would occur. That leaves the bass with

1

ˆ

as the last and only option. Thus, a “root-position” inverted cadential six-four

chord appears on the downbeat of m. 104.

14

Another reason why this unusual

version of V

6

4

stands out is because Bach arpeggiates II

6

5

with a final D in the

bass, and reiterating this pitch over the barline renders it more noticeable.

15

With these examples in mind, it is beneficial to take a fresh look at some

instances of root-position and first-inversion tonic triads. If reevaluating their

function is justified in certain situations, it also is tempting to find only what

one is searching for based on a priori decisions. In Example 12, the I

6

in m. 10

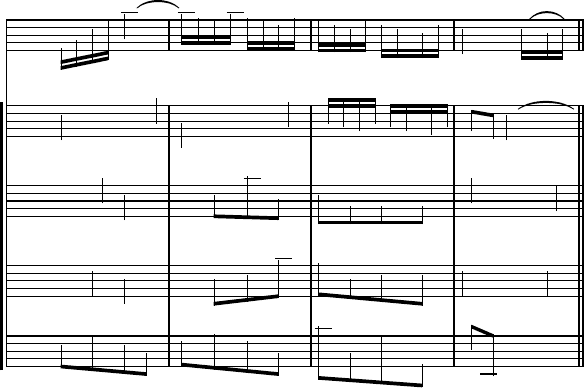

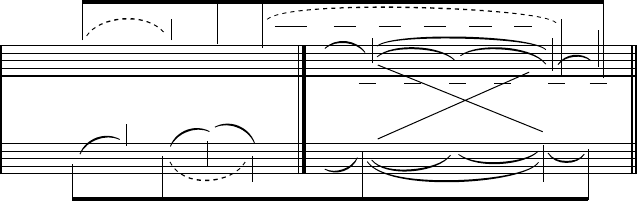

Example 10. J. S. Bach, Violin Concerto no. 1, BWV 1041, mvt. 1, mm. 143–46

cutler_10 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Š

Š

š

Ý

.

0

.

0

.

0

.

0

.

0

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¹

¹

¹

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¹

¹

¹

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

$

%

Solo

Violin

Violin I

Violin II

Viola

Continuo

I6a: IV V

6

4

7

I

143

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 10

14 In m. 103, the C≥ in the second violin provides a mod-

est dominant push from the predominant harmony to the

inverted cadential six-four in m. 104. This technique is com-

mon in these situations: Surface dominants, such as V

4

2

or VII

4

3

, can replace the predominant (e.g., Mozart, String

Quartet K. 421, mvt. 1, mm. 93–94) or embellish the

motion from predominant to inverted V

6

4

. Examples of the

latter include Mendelssohn, Violin Concerto op. 64, mvt. 2,

mm. 38–40; Mozart, Piano Sonata K. 333, mvt. 2,

mm. 19–20 (see Example 14); and J. S. Bach, Partita no.

2 for Unaccompanied Violin, BWV 1004, Sarabande, m. 22

(see Examples 22 and 30).

15 Compositions for solo string instruments are a particu-

larly fertile ground for the discovery of inverted cadential

six-four chords. The Sarabande from Bach’s Cello Suite no.

1, BWV 1007, features a prominent dominant-function “I

6

”

chord in m. 15. The Paganini caprices for solo violin contain

numerous instances of inverted V

6

4

chords. In the Caprice

in G minor, op. 1/6, the downbeat of m. 10, which has

the visual appearance of “I

5

3

,” possesses cadential six-four

function due to its harmonic context. Measures 14–15 in

the Caprice in C minor, op. 1/4, present a more extreme

situation: Root-position Neapolitan harmony is followed by

a “root-position” inverted V

6

4

, complete with implied paral-

lel octaves and fifths. In numerous examples from the solo

string repertoire the inverted position of the cadential six-

four results from the registral or technical limitations of the

instruments.

202

JOUrnAl of MUSIc ThEOrY

of Schubert’s “Du bist die ruh,” D. 776, can be read in two ways: as a dis-

sonant inverted cadential six-four chord or a relatively stable first-inversion

tonic triad. According to Example 12b, mm. 8–11 are derived from a I–(VI)–

V–I progression; the visual I

6

chord in m. 10 functions as an inverted V

6

4

.

This interpretation highlights a rising fourth-span that Schubert modifies in

mm. 54–57. Example 12c views mm. 8–11 as a 5–6–5 embellishment above a

prolonged tonic, and there is no operative predominant in m. 9. The overall

harmonic progression is I–(I

6

)–V

7

–I without the presence of an inverted V

6

4

. I

have a preference for the latter interpretation, although I do not believe the

former should be summarily dismissed.

16

Creating consistency: Voice exchanges and motivic connections

rarely is a functional voice exchange an end to itself. Usually it points to

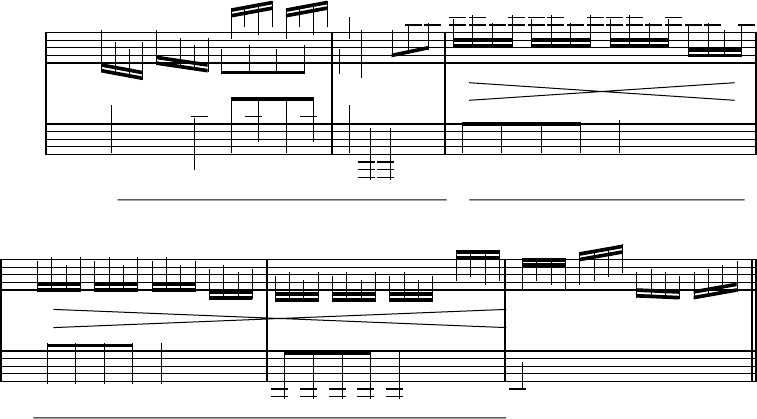

other significant musical features. In the first movement of the Piano Sonata

K. 310, Mozart begins the second key area with I

6

rather than the more custom-

ary I

5

3

(Example 13). Greater stability is achieved three measures later when

cutler_11 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Š

Š

š

Ý

.

0

.

0

.

0

.

0

.

0

Ł

Ł

¹

¹

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

¹

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł−

¹

¹

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł−

Ł

Ł

¹

Ł−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

Ł²

Ł−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¾

Ł

¹

¹

¼

Ł

Ł²

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

$

%

Solo

Violin

Violin I

Violin II

Viola

Continuo

I6d: II

6

5

V

6

4

(NOT I

5

)

7I

3

102

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 11

Example 11. Bach, BWV 1041, mvt. 1, mm. 102–5

16 It is also worth noting that inverted accented six-four

chords can explain some occurrences of the “forbid-

den” progression V

(7)

–IV. The IV chord would represent an

inverted version of an accented six-four, I

6

4

, that eventu-

ally resolves to I

5

3

. Examples of this are found in Berwald’s

Violin Concerto op. 2, mvt. 1, mm. 1–3; the climactic final

cadence of “Nessun Dorma” from the third act of Puccini’s

Turandot (“All’alba vincerò!”); and “Isolde’s Liebestod” from

the third act of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde (“In dem wogen-

den Schwall, in dem tönenden Schall, in des Welt-Atems

wehendem All -”). In these excerpts the V

(7)

–IV–I progres-

sions produce hybrid authentic/plagal cadences.

203

Timothy Cutler On Voice Exchanges

Mozart arrives at root-position tonic harmony. The relationship between the

two chordal positions is fortified by a voice exchange in the outer voices and

defines mm. 23–26 as a region of c-major tonic prolongation. This exchange

also underscores the bass motion from 3

ˆ

to 1

ˆ

, calling attention to a hidden

motivic connection. Prior to this bass descent, Mozart arrives at the dominant

of c major in m. 16 and sustains it for seven measures. Thus, the bassline lead-

ing into and commencing the second key area consists of G–E–c, an eleven-

measure unfolding of the tonic triad in c major. This extended descending

arpeggio comes directly from the primary theme of the movement. What

makes this lengthy motivic parallelism unusual is that it unfolds across more

than one formal section: It begins during the exposition’s bridge passage but

is not completed until the second key area already has started.

We previously considered analytical hypotheses—some good, others less

so—involving voice exchanges in the second movement of Mozart’s Piano

Sonata K. 333 (see Example 2). Voice exchanges, especially of the 10–8–6

variety, abound from the beginning of the movement, starting with the bass

and alto voices in m. 2. For such a common contrapuntal technique to occur

frequently within a piece is not unusual. In this movement, however, there are

cutler_12a (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Š

Ý

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

/

4

/

4

/

4

Ł

Ł

Ł

\\

Ł

Ł

ý

Ł

Ł

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

�

Ł

Łý

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

!

Voice

Piano

8

Langsam

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 12a

(a)

cutler_12b-c (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Ł

Ł

Ł−

Ł

Ł

−

−

Ł

Ł−

Š

−

−

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ŁŁ

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

()

mm. 8–11

IE

−

:V

6

4

7I

(mm. 54–57)

I

5

mm. 8–11

65

V7 I

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 12b-c

(b) (c)

Example 12. Schubert, “Du bist die Ruh,” D. 776, mm. 8–11 (a–c)

204

JOUrnAl of MUSIc ThEOrY

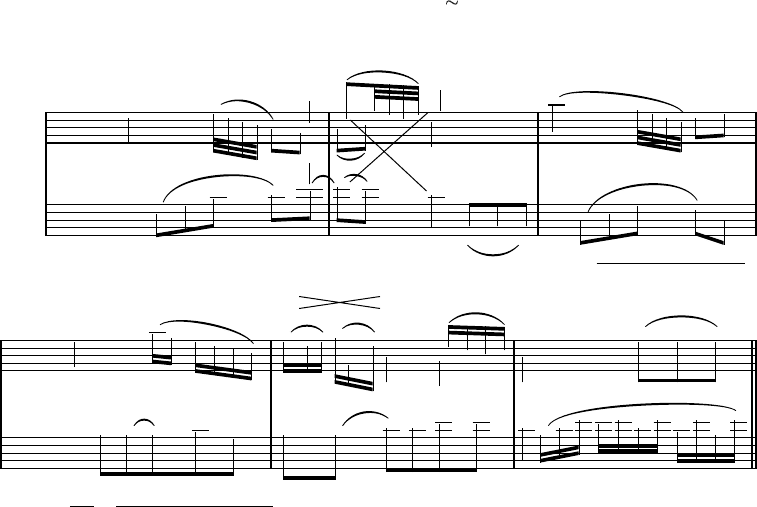

more specific interrelationships taking place during the exposition. In partic-

ular, the ascending stepwise motive D–E≤–F is combined with voice exchanges

and the interplay of structural levels to bring about a more organic composi-

tion (Example 14).

Third-progressions are a central fixture of the second movement. Within

the first key area of the exposition, there are isolated examples of stepwise

ascending thirds, such as the bass in m. 2 (highlighted by Mozart’s slur mark-

ing), that counterbalance the numerous utterances of descending thirds. Yet

there are no obvious manifestations of the specific third-progression D–E≤–F

until the second key area arrives in m. 14. Even in the new key of B≤ major,

straightforward references to the D–E≤–F motive only occur in the right-

hand thirty-second notes in m. 17, the left hand of m. 20, the inner voices of

mm. 23 and 27, and to a lesser degree m. 31.

17

The motives in mm. 23 and 27

are underscored by slur markings and form voice exchanges with the soprano.

As we will see, voice exchanges are a common denominator in hearing the

relationships between various utterances of the D–E≤–F motive.

These pitches do not occur in the second key area by accident—Mozart

foreshadows them prior to the arrival of the dominant. The first key area is

structured around three descending linear progressions, all departing from

the dominant scale degree. The first descends a minor sixth to D (mm. 1–4),

the second moves down a perfect fifth to E≤ (mm. 5–8), and the last linear

cutler_13 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

77777

Š

Š

Ý

�

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

[

Ł

Ł

Ł

¹

Ł

Ł−

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¹

Ł

l

\

¼

Ł

l

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

Ł

\

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¼

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Š

Š

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¼

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¼

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¼

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

½

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

!

!

Piano

GE

C

E

C

E

C

21

24

Allegro maestoso

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 13

Example 13. Mozart, Piano Sonata K. 310, mvt. 1, mm. 21–26

17 I also perceive the D–E≤–F motive in the left hand of

m. 29.

205

Timothy Cutler On Voice Exchanges

progression falls a perfect fourth to F (mm. 8–13). The terminal pitches of

these linear progressions—D, E≤, and F—do not suggest the unfolding of a

portion of a B≤ major triad in the key of the dominant (with E≤ as passing).

nevertheless, for the same reason that one avoids writing dissonant contours

in species counterpoint, the terminal pitches of these stepwise descents leave

aural imprints.

With the seeds of the D–E≤–F motive planted, its appearance in the sec-

ond key area is subtly prepared. In fact, one finds the motive on two structural

levels in m. 17, both on the surface and slightly beneath it. coinciding with

this motive is a voice exchange that is reminiscent of mm. 23 and 27. The

same concepts—a motive unfolding simultaneously on two structural levels

and the presence of a voice exchange—also take place in m. 20.

18

The outer

voices, D and F, create a potential exchange between the first and second

beats. Top-voice D is transferred to an inner voice on beat 2, although its pres-

ence is still felt in the higher register, where it returns on the third beat as a

literal appoggiatura and an implied suspension. The legitimacy of this voice

exchange hinges on one’s harmonic interpretation of the passage. A cursory

glance at m. 20 reveals a first-inversion tonic progressing through a passing

chord to a dominant-function cadential six-four. This would seem to rule out

cutler_14 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:09 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

−

−

−

−

−

−

/

0

/

0

¹

Łý

\

Ł

Ł¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

�

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

�

�

Ł

¹

l

Ł

¼

l

Ł

l

¹

Ł

ý

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

o

o

Š

Ý

−

−

−

−

−

−

¹

Ł

ý

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

Ł¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

�

Ł

^[

Ł

Ł

Ł

¹

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

l

[

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

l

Ł

!

!

3

3

Piano

DE

−

DE

−

F

F

D

E

−

F

D

D

F

E

−

F

F

D

16

19

Andante cantabile

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 14

Example 14. Mozart, K. 333, mvt. 2, mm. 16–21

18 Chopin’s Prelude op. 28/17 contains an instance of three

identical motives unfolding simultaneously on three differ-

ent structural levels. See my commentary on mm. 43–51

elsewhere in this article.

206

JOUrnAl of MUSIc ThEOrY

the presence of a functional voice exchange in m. 20. however, by recalling

the concept of the inverted cadential six-four, a preferable solution becomes

evident.

Measure 19 possesses unequivocal predominant function that is fortified

by its tonicization in the previous measure. Despite the ensuing appearance of

“I

6

,” the voice exchange in m. 20 suggests that a single harmonic idea is being

prolonged—the downbeat functions as an inverted V

6

4

that unites with a literal

V

6

4

one beat later. From this observation a slightly different bassline emerges

with D (m. 18) ascending to E≤ (m. 19) and culminating with F (m. 20). hence,

manifestations of the D–E≤–F idea in both mm. 17 and 20 are nested within

broader forms of the motive. And, the motive coincides with voice exchanges

in mm. 17, 20, 23, and 27. To complete the motivic network, the genesis of this

idea occurs at the beginning of the movement, where the third-span B≤–A≤–G

occurs not only in the first measure but also as an expanded version encom-

passing mm. 1–2, where a voice exchange is present in the lower two parts.

Shaping structure: Long-range voice exchanges

One of the most persuasive tools for organizing extended musical passages

is the long-range voice exchange. Voice exchanges unify a common har-

monic idea and make what occurs within its boundaries subservient to the

harmonic and voice-leading implications of the exchange itself. long-range

pitch trades, such as the chromatic voice exchange that leads from the tonic

to an augmented-sixth chord in preparation for V of V, can elucidate the

hierarchical value of material that might otherwise be easy to misinterpret.

roger Kamien and naphtali Wagner write, “An awareness of long-range chro-

maticized voice exchange can often help clarify problematic formal divisions

within the exposition” (1997, 2). In particular, this technique can clear up the

meaning of dominant material that arrives, as it were, too early during the

transition from tonic to dominant in sonata-form expositions. For example,

the G-minor bridge theme in the first movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata

op. 2/3 is not the main theme of the second key area because it is subsumed by

a chromatic voice exchange spanning mm. 1–42, and not because it is in the

“wrong” mode. In contrapuntal terms, the G-minor music supports the pass-

ing tone D within the expanded upper line E–D–c≥. The structural entrance

of the dominant does not occur until m. 47.

The exposition is not the only location where long-range chromatic voice

exchanges can influence sonata-form structure. In “Programmatic Aspects of

the Second Sonata of haydn’s Seven Last Words,” lauri Suurpää (1999) offers

insightful analysis of one of haydn’s most beautiful compositions. Stem-

ming from the movement’s introductory sentence, “Today you will be with

me in paradise,” Suurpää views the work as representing a tripartite spiritual

journey: (1) an initial state of agony, (2) “the promise of the forthcoming

paradise,” and (3) “the actual arrival in paradise” (1999, 30). his weaving

207

Timothy Cutler On Voice Exchanges

of symbolic imagery with concrete compositional aspects is convincing, and

his commentary is lucid and penetrating. Meanwhile, there is one analytical

conclusion to which I shall offer an alternative viewpoint. I do not think that

Suurpää’s reading is incorrect, per se; our conclusions simply represent the

contrasting (and reasonable) priorities of two musicians. My interpretation is

guided by a long-range chromatic voice exchange that shifts the tonal climax

of the development section to a different location.

The first version of haydn’s Seven Last Words of Our Saviour on the Cross

was written for orchestra in 1786. The second movement, in c minor, is com-

posed in monothematic sonata form. The exposition flows expectedly from

the tonic to the mediant. haydn immediately establishes the subdominant

as the starting point of the development section and through an ascending

chromatic sequence arrives at the minor dominant several measures later. The

mode of the dominant is soon “corrected,” which brings about the end of

the development. The c-major recapitulation represents an extended Picardy

idea. Due to transpositions of key and mode, redundant material from the

exposition—namely, the first key area—is omitted, and the movement ends

in the blissful paradise of c major.

cutler_15 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

−

−

−

−

−

−

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

�

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

²

¦

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

¦

!

““

Ic:

m. 1 16

III

21 29 30 50

(IV)

51 62

V

69

−

3

¦

3

76

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 15

Example 15. Haydn, Seven Last Words op. 51/2, exposition and development (after Suurpää)

Suurpää’s conclusions regarding the movement’s first branch certainly

make sense, and the techniques illustrated by his voice-leading graph can be

applied to many works (Example 15). Employing the subdominant as a pass-

ing key area between the mediant and dominant is a typical sonata-form pro-

cedure. haydn features the same setup in the first movement of the String

Quartet op. 64/2 (Anson-cartwright 1998, 106, 271). Other minor-mode

developments that use the subdominant as a passing chord between III and

V include the first movements of Mozart’s Piano Sonatas K. 310 and K. 457

and Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas op. 2/1 and op. 13 (cadwallader and Gagné

1998, 343–47, 410 n. 37). Written in the same key as the second movement

of haydn’s Seven Last Words, the opening movement of Mozart’s Piano Sonata

208

JOUrnAl of MUSIc ThEOrY

K. 457 features various ideas that are present in haydn’s composition: uniting

the mediant of the exposition with the dominant of the development with

a passing subdominant, immediately tonicizing IV at the beginning of the

development, using an implied ascending chromatic sequence to advance the

bassline from E≤ through F and toward G, and arriving at the minor dominant

before the leading tone and major dominant enter.

Another composition that exhibits similar traits is the first movement

of Beethoven’s String Trio in c minor, op. 9/3. Its development section also

uses the subdominant as a passing chord between the mediant and minor

dominant. compared to his younger contemporaries’ works, however, there is

something unique about the manner in which haydn treats the minor domi-

nant in his development section. In the Mozart sonata, minor V enters in m.

87 and lasts for two measures before it is “corrected” by the leading tone. The

remainder of the development section stays firmly focused on the dominant,

and there is no doubt that the bass has reached its final resting stop in the first

branch of the large-scale structure, 5

ˆ

, in m. 87. In the development section of

the String Trio, Beethoven approaches the minor dominant through a differ-

ent sequence. Once established, minor V receives more weight than it does in

Mozart’s composition—roughly one-third of Beethoven’s development occurs

in the key of G minor. Beethoven’s transition from minor to major V is more

elaborate than Mozart’s, but once G minor enters midway through the devel-

opment, the music stays fixed on the dominant, whether the mode is minor

or major.

cutler_16 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

−

−

−

−

−

−

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

�

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

²

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

¦

!

““

Ic:

m. 1 16

III

21 29 30

5

50

(6)

(IV)

51

5

62

6

(P)

69

5

71

6

75

5

V

5

76

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 16

Example 16. Haydn, op. 51/2, exposition and development (alternative reading)

The same cannot be said for haydn’s development. Even if haydn pro-

vides the minor dominant with substantial harmonic preparation, the events

after the entrance of minor V undermine its status as a primary arrival point.

like Mozart, haydn uses an implied ascending chromatic 5–6 sequence to

push from the mediant through the subdominant and toward the dominant

(Example 16). But unlike the developments by Mozart and Beethoven, in

209

Timothy Cutler On Voice Exchanges

haydn’s composition the material immediately following the arrival of minor

V renders G minor less stable. In m. 71, an unexpected thematic outburst in

E≤ major calls into question the stability of G minor as the first step in the

establishment of G as structural dominant. The expanded orchestration and

sudden forte make the previous G-minor thematic statement sound transi-

tory in retrospect, as if it is still building toward a more significant event. This

is explained by the sequence that propels the development section forward:

Whereas the sequences by Mozart and Beethoven end with the entrance of

minor V, suggesting that this harmony is a paramount point of arrival, haydn’s

ascending 5–6 sequence is not yet complete. The E≤ major thematic statement

represents a hidden continuation of the ascending 5–6 idea. Although the

sequence is modified when G minor enters in m. 69—it is not the same chro-

matic version as it was prior to the minor dominant—the lowest voice wants to

ascend one semitone above G. It marks A≤, 6

ˆ

in m. 75, and not the dominant

in m. 69, as the true goal of the 5–6 sequence that commenced from III. Built

upon A≤ is a German augmented sixth, and these “dominatizing” harmonies

often indicate the arrival of crucial structural events.

The German augmented sixth is not an independent harmonic idea—

it grows organically out of previous material. When haydn modulates to the

subdominant in mm. 49–51, he does so economically with a single secondary

dominant, V

7

of IV. he scores this applied chord with the seventh in the high-

est voice so that A≤, the resolution of the seventh, sounds like a leading voice

when the development begins. Emphasis on IV and the melodic tone A≤ are

what prepare the German augmented-sixth chord in m. 75: The augmented

sixth represents a logical outgrowth of the subdominant that began in m. 51

because the two harmonies create an extended chromatic voice exchange

that spans nearly the entire development section.

19

By utilizing the long-range

chromatic voice exchange to determine the overall shape of the development,

structural tension is maintained until the entrance of the major dominant in

m. 76. The statement of the main theme in G minor is no longer a principal

arrival point in the development—the bass has not yet settled on structural 5

ˆ

.

G minor is a passing element within the unfolding of the extended chromatic

voice exchange. (To my ears, the main drawback of Suurpää’s interpretation

is that musical tension resolves prematurely.) root-position triads are used

somewhat infrequently as passing chords that connect the tones of a voice

exchange, but even the heavy stability of a five-three triad can be convincingly

transformed into a passing entity when surrounded by the powerful influence

of a voice exchange.

20

19 Neither Mozart’s Sonata K. 457 nor Beethoven’s String

Trio op. 9/3 feature long-range chromatic voice exchanges in

their first-movement development sections. The first move-

ment of Mozart’s Piano Sonata K. 310 employs a chromatic

voice exchange between IV and a German augmented sixth,

although it spans only a small portion of the development

section (mm. 70–73).

20 J. S. Bach employs a passing V between IV and IV

6

in

m. 20 of the Chorale no. 102. Brahms uses root-position

III≥ as a passing chord between II and II

6

in mm. 5–6 of

“An die Nachtigall,” op. 46/4. The first movement of Mozart’s

Eine Kleine Nachtmusik K. 525 features a chromatic voice

exchange—C/E in m. 60 become E≤/C≥ in mm. 68–69—that

spans nearly the entire development, albeit on a smaller

210

JOUrnAl of MUSIc ThEOrY

This interpretation also illuminates certain motivic connections.

Suurpää points out that haydn contrasts the color and function of A≤ and AΩ

throughout the movement. A≤, which Suurpää equates with suffering, and the

falling motive A≤–G dominate the exposition, including mm. 2 (where the vio-

las, with their distinct tone color, leap over the second violins), 4–7, and 9–12.

AΩ, symbolizing paradise, governs the recapitulation, although it is featured as

early as m. 19. In the development, there is a greater struggle for supremacy

between A≤ and AΩ. The latter pitch triumphs on the surface (m. 79), while

the former dominates on a deeper level due to the long-range chromatic

exchange. The A≤–G motive, which originated as an inconspicuous melodic

idea in mm. 2 and 4, evolves into a colossal motivic enlargement: A≤ begins in

m. 51 in an upper voice and is transferred to the bass at the conclusion of the

voice exchange, followed by its resolution to 5

ˆ

. This descending gesture reigns

over almost the entire development and persists for nearly thirty measures.

Therefore, the appearance of AΩ during the passage in the minor dominant

can be considered a fleeting mirage because passing G minor is still under the

control of subdominant unfolding.

21

Motivic activity culminates in m. 76 when the chromatic voice exchange

resolves to the dominant. The horns in c sustain a dominant pedal and then

ascend by perfect fourth. This points to one of the movement’s primary ideas—

the contrast between descending and ascending fourths (which undoubtedly

possesses symbolic meaning) cast in both major- and minor-mode contexts.

This motive initially appears in the first violins in mm. 3–4. The violas unfold

the same ascending fourth in mm. 76–77, one that foreshadows identical

pitches in a different context in mm. 83–84. Meanwhile, the second violins

play a variant in mm. 76–77, B–c–D–E≤, which is derived from the melodic line

E≤–D–B–c that first arises in mm. 1–2 and is repeated in the bass (with viola

doubling) in mm. 6–8. The resolution of the chromatic voice exchange also

italicizes an expanded version of the original c–B≤–A≤–G motive. Embedded

across mm. 51–76 is an implied, primarily chromatic line c–D–E≤–E–F–F≥–G.

This inversion of the descending fourth is cast upward toward paradise,

which is confirmed in m. 81 with the arrival of c major. Finally, the large-scale

chromatic voice exchange points to an even more remarkable motivic paral-

lelism: The development unfolds the melodic line A≤–G–F≥–G in an upper

scale than the compositions discussed currently. What

makes this example unusual is that the transformation of

the subdominant into an augmented sixth occurs within the

development section of a major-mode composition. Since

structural V has already been achieved, the unfolding of IV

(m. 60) is neighboring rather than passing. Mozart uses an

implied 5–6–5 motion (mm. 60–67) to pass through a root-

position dominant on its way to a German augmented sixth

in mm. 68–69. Just as the G-minor music in Haydn’s Seven

Last Words is passing within a chromatic voice exchange,

so too is the brief utterance of the dominant in m. 67 of the

first movement of Eine Kleine Nachtmusik.

21 At the end of the exposition in m. 47, A≤ and AΩ occur

simultaneously. Concurrently, the oboe states the A≤–G

motive. Two measures later the first violin continues with

B≤ and its implied resolution to A≤. Combining the oboe and

violin dyads unfolds a hidden motivic reference to the upper

voice in mm. 9–12.