Cobbs-Hoffman Elizabeth, Blum Edward J., Gjerde Jon. Major Problems in American History, Volume I, 3 edition (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Tis estimated by some that this Army has been reduced to at least one fifth

its original strength. Charleston is closely b eset, and I think must surely fall

sooner or later. The fall of Vicksburg has caused m e to lose confidence in

something or somebody, I can’t say exactly which. And now that gunboats

from the Mississippi can be transferred to Charleston and that a portion of

Morris Island has been taken and can be used to advantage by the enemy,

I fear greatly the result of the attack. I trust however, if it does fall, its gallant

defenders will raze it to th e groun d that the enemy can not find a single s pot to

pitch a tent upon the site where so magnificent a city once raised, so excitingly,

its towering head. Savannah will f ollow, and then Mobile, and fi nally

Richmond.

These cities will be a loss to the Confederacy. But their fall is no reason

why we should despair. It is certainly calculated to cast a gloom over our

entire land. But we profess to be a Christian people, and we sh ould put

our trust in God. He h olds the des tiny of our n ation, as it were, in the

palm of his ha nd. He it is that directs the counsel of our leaders, both civil

and military, and if we place implicit confidence in Him and go to work in

good earnest, never for a moment losing sight of Heaven’s goodness and pro-

tection, it is my firm belief that we shall be victorious in the end. Let the

South lose what it may at present, God’s hand is certainly in this contest,

and He is working for the accomplishment of some grand result, and so

soon as it is accomplished, He will roll the sun of peace up the skies and

cause its rays to shine over our whole land. We were a w icked, proud, am-

bitious nation, and God has brought upon us this war to crush and humble

our pride and make us a better peo ple g enerally. And the sooner this happens

the better for us….

Your ever affec cousin

T. N. Simpson

James is quite well and stands these marches finely. He sends his love to his

family and to all the negros generally. He likewise wishes to be remembered to

his master and all the white family.

6. Mary A. Livermore, a Northern Woman,

Recalls Her Role in the Sanitary Commission, 1863

Organizations of women for the relief o f sick an d wo unded soldiers, and for

thecareofsoldiers’ families, were formed with great spontaneity at the very

beginning of the war. There were a dozen or m ore of them in Chicago, in

less than a month after Cairo was occupied by Northern troops. They raised

money, prepared and forwarded supplies of whatever was demanded, every

Mary A. Livermore, My Story of the War: A Woman’s Narrative of Four Years Personal Experience (Hartford, Conn.:

A. D. Worthington and Company, 1889), 135–137.

THE CIVIL WAR

423

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

shipment being accompanied by some one who was hel d respon sible f or the

proper disbursement of the stores. Sometimes these local societies affiliated

with, or became parts of, more comprehensive organizations. Most of them

worked independently during the first year of the war, the Sanitary Commis-

sion of Chicago being only one of the relief agencies. But the Commission

gradually grew in public confiden ce, and gained in sco pe and power; and al l

the local soci eties were eventually m erged in it, or became auxiliary to it. As

in Chicago, so throughout the country. The Sa nitary Commission became the

great channel, through which the patriotic b eneficence of the nation flowed to

the army….

Here, day after day, the drayman left boxes of supplies sent from aid

societies in Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, and Indiana. Every box

contained an assortment of articles, a list of which was tacked on the inside of the

lid….

One day I went into the packing-room to learn the secrets of these boxes,—

everyone an argosy of love,—and took notes during the unpacking. A capacious

box, filled with beautifully made shirts, drawers, towels, socks, and handker-

chiefs, with “comfort-bags” containing combs, pins, needles, court-plaster, and

black sewing-cotton, and with a quantity of carefully dried berries and peaches,

contained the following unsealed note, lying on top:—

D

EAR SOLDIERS,—The little girls of—send this box to you. They hear

that thirteen thousand of you are sick, and have been wounded in

battle. They are very sorry, and want to do something for you. They

cannot do much, for they are all small; but they have bought with their

own money, and made what is in here. They hope it will do some

good, and that you will all get well and come home. We all pray to

God for you night and morning….

Another mammoth packing-case was opened, and here were folded in bles-

sings and messages of love with almost every garment. On a pillow was pinned

the following note, unsealed, for sealed notes were never broken:—

M

Y DEAR FRIEND,—You are not my husband nor son; but you are the

husband or son of some woman who undoubtedly loves you as I love

mine. I have made these garments for you with a heart that aches for

your sufferings, and with a longing to come to you to assist in taking

care of you. It is a great comfort to me that God loves and pities you,

pining and lonely in a far-off hospital: and if you believe in God, it will

also be a comfort to you. Are you near death, and soon to cross the dark

river? Oh, then, may God soothe your last hours, and lead you up “the

shining shore, ” where there is no war, no sickness, no death. Call on

Him, for He is an ever-present helper.

424 MAJOR PROBLEMS IN AMERICAN HISTORY

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

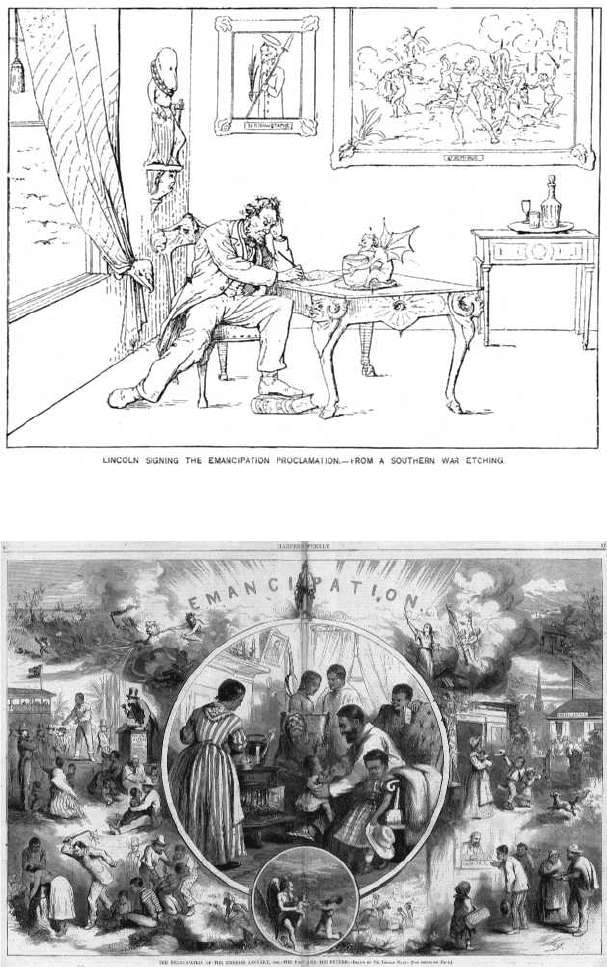

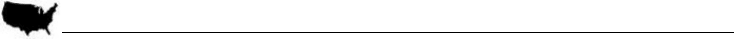

7. Two Artistic Representation of Emancipation, 1863, 1864

EMANCIPATION CARTOON. Abraham Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation—a

Southern point of view. Reproduction of an etching from Adalbert J. Volc k’s Confederate War Etchings.

This Harper’s Weekly cartoon by Thomas Nast celebrates the Emancipation Proclamation by President

Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863.

The Granger Collection, NY

HarpWeek

THE CIVIL WAR 425

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

8. Congressman Clement Vallandigham

Denounces the Union War Effort, 1863

The men who are in power at Washington, extending their agencies out

through the cities and states of the Union and threatening to reinaugurate a reign

of terror, may as well know that we comprehend precisely their purpose. I beg

leave to assure you that it cannot and will not be permitted to succeed. The

people of this country endorsed it once because they were told that it was essen-

tial to “the speedy suppression or crushing out of the rebellion” and the restora-

tion of the Union; and they so loved the Union of these states that they would

consent, even for a little while, under the false and now broken promises of the

men in power, to surrender those liberties in order that the great object might, as

was promised, be accomplished speedily.

They have been deceived; instead of crushing out the rebellion, the effort

has been to crush out the spirit of liberty. The conspiracy of those in power is

not so much for a vigorous prosecution of the war against rebels in the South as

against the democracy in peace at home….

… Now, if in possession of the purse and the sword absolutely and unquali-

fiedly, for two years, there be anything else wanting which describes a dictator-

ship, I beg to know what it is….

I will not consent to put the entire purse of the country and the sword of

the country into the hands of the executive, giving him despotic and dictatorial

power to carry out an object which I avow before my countrymen is the de-

struction of their liberties and the overthrow of the Union of these states….

The charge has been made against us—all who are opposed to the policy of

this administration and opposed to this war—that we are for “peace on any

terms.” It is false. I am not, but I am for an immediate stopping of the war and

for honorable peace. I am for peace for the sake of the Union of these states….

[A]nd I, unlike some of my own party, and unlike thousands of the Aboli-

tion Party, believe still, before God, that the Union can be reconstructed and

will be. That is my faith, and I mean to cling to it as the wrecked mariner clings

to the last plank amid the shipwreck.

9. Abraham Lincoln Calls for Peace and Justice

in His Second Inaugural Address, 1865

On the occasion corresponding to this four years ago, all thoughts were anx-

iously directed to an impending civil-war. All dreaded it—all sought to avert it.

While the inaugural address was being delivered from this place, devoted alto-

gether to saving the Union without war, insurgent agents were in the city seek-

ing to destroy it without war—seeking to dissolve the Union, and divide effects,

Clement Vallandigham’s Copperhead Dissent (1863), in Speeches, Arguments, Addresses, and Letters of Clement L. Vallandigham,

Clement L.Vallandigham (New York: J. Walter and Co., 1864), 479–502.

Abraham Lincoln, Second Inaugural Address, 1865.

426 MAJOR PROBLEMS IN AMERICAN HISTORY

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

by negotiation. Both parties deprecated war; but one of them would make war

rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let

it perish. And the war came.

One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed

generally over the Union, but localized in the Southern part of it. These slaves

constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was,

somehow, the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this in-

terest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union, even by

war; while the government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the ter-

ritorial enlargement of it. Neither party expected for the war, the magnitude, or

the duration, which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of

the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease.

Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding.

Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid

against the other…. If we shall suppose that American Slavery is one of those

offences which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having

continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He

gives to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by

whom the offence came, shall we discern therein any departure form those di-

vine attributes which the believers in a Living God always ascribe to Him?

Fondly do we hope —fervently do we pray—that this mightly scourge of war

may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth

piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be

sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another

drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be

said “the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether”.

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as

God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to

bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle,

and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a

just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

ESSAYS

The Civil War ended slavery, but historians have debated who was most respon-

sible for the Emancipation Proclamation. James M. McPherson, professor emeri-

tus of history at Princeton University, stresses the political genius of Abraham

Lincoln, arguing that Lincoln played a crucial role in engineering three revolu-

tions during the Civil War, one of which was the abolition of slavery. Professor

McPherson emphasizes the political difficulties that Lincoln faced in bringing

about abolition. Although Lincoln moved cautiously during the early years of

war, his proclamation of emancipation completely changed the meaning of the

war because it proclaimed a revolutionary new aim of the war. A group of scho-

lars led by Ira Berlin, a member of the department of history at the University of

THE CIVIL WAR 427

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Maryland, argues in contrast that the responsibility for the Emancipation Procla-

mation lies with the slaves themselves. President Lincoln, he contends, entered

the Civil War only to save the Union, and Confederate leaders were convinced

that slavery would endure. It was the actions of slaves, he argues, that forced

Lincoln to come to terms with emancipation. By moving to the Union army,

they not only aided the war effort, but ultimately forced the issue. If he began

as a president intent only on saving the Union, Lincoln ultimately became

known as the Great Emancipator. But his legacy would not have occurred, Pro-

fessor Berlin and his colleagues believe, had it not been for African Americans’

forcing the issue.

The Role of Abraham Lincoln in the Abolition of Slavery

JAMES M. MCPHERSON

The foremost Lincoln scholar of a generation ago, James G. Randall, considered

the sixteenth president to be a conservative on the great issues facing the coun-

try, Union and slavery. If conservatism, wrote Randall, meant “caution, prudent

adherence to tested values, avoidance of rashness, and reliance upon unhurried,

peaceable evolution, [then] Lincoln was a conservative.” His preferred solution

of the slavery problem, Randall pointed out, was a program of gradual, compen-

sated emancipation with the consent of the owners, stretching over a generation

or more, with provision for the colonization abroad of emancipated slaves to

minimize the potential for racial conflict and social disorder. In his own words,

Lincoln said that he wanted to “stand on middle ground,” avoid “dangerous ex-

tremes,” and achieve his goals through “the spirit of compromise … [and] of mu-

tual concession.” In essence, concluded Randall, Lincoln believed in evolution

rather than revolution, in “planting, cultivating, and harvesting, not in uprooting

and destroying.” Many historians have agreed with this interpretation. To cite

just two of them: T. Harry Williams maintained that “Lincoln was on the slavery

question, as he was on most matters, a conservative”; and Norman Graebner

wrote an essay entitled “Abraham Lincoln: Conservative Statesman,” based on

the premise that Lincoln was a conservative because “he accepted the need of

dealing with things as they were, not as he would have wished them to be.”

Yet as president of the United States, Lincoln presided over a profound,

wrenching experience which, in Mark Twain’s words, “uprooted institutions

that were centuries old, changed the politics of a people, transformed the social

life of half the country, and wrought so profoundly upon the entire national

character that the influence cannot be measured short of two or three

generations.” Benjamin Disraeli, viewing this experience from across the Atlantic

in 1863, characterized “the struggle in America” as “a great revolution…. [We]

will see, when the waters have subsided, a different America.” The Springfield

Excerpt from James M. McPherson is reprinted from Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution, ed. John

Thomas (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1986), copyright © 1986 by University of Massachusetts

Press. Used with permission.

428 MAJOR PROBLEMS IN AMERICAN HISTORY

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

(Mass.) Republican, an influential wartime newspaper, predicted that Lincoln’s

Emancipation Proclamation would accomplish “the greatest social and political

revolution of the age.” The historian Otto Olsen has labeled Lincoln a revolu-

tionary because he led the nation in its achievement of this result.

As for Lincoln himself, he said repeatedly that the right of revolution, the

“right of any people” to “throw off, to revolutionize, their existing form of gov-

ernment, and to establish such other in its stead as they may choose” was “a

sacred right—a right, which we may hope and believe, is to liberate the

world.” The Declaration of Independence, he insisted often, was the great

“charter of freedom” and in the example of the American Revolution “the

world has found … the germ … to grow and expand into the universal liberty of

mankind.” Lincoln championed the leaders of the European revolutions of l848;

in turn, a man who knew something about those revolutions—Karl Marx—

praised Lincoln in 1865 as “the single-minded son of the working class” who

had led his “country through the matchless struggle for the rescue of an en-

chained race and the reconstruction of a social world.”

What are we to make of these contrasting portraits of Lincoln the conser-

vative an d Lincoln the revolutionary? Are they just another example of how

Lincoln’s words can he manipulated to support a ny position, even diametrically

opposed ones? No. It is a matter of interpretation and emphasis within the con-

text o f a fluid and rapidly changing crisis situation. The Civil War started out as

one kind of conflict and ended as some thing quite different. These apparently

contradictory positions about Lincoln the conservative versus Lincoln the revo-

lutionary can be reconcil ed by focusing on this process. The attempt to recon-

cile them can tell us a great deal about the nature of the American Civil War.

That war has been viewed as a revolution—as the second American

Revolution—in three different se nses. Lincoln played a crucial role in defin-

ing the outcome of the revolution in each of three respects.

The first way in which some contemporaries regarded the events of 1861 as

a revolution was the frequent invocation of the right of revolution by southern

leaders to justify their secession —their declaration of independence—from the

United States. The Mississippi convention that voted to secede in 1861 listed

the state’s grievances against the North, and proclaimed: “For far less cause than

this, our fathers separated from the Crown of England.”…

For Lincoln it was the Union, not the Confederacy, that was the true heir of

the Revolution of 1776. That revolution had established a republic, a democratic

government of the people by the people. This republic was a fragile experiment

in a world of kings, emperors, tyrants, and theories of aristocracy. If secession

were allowed to succeed, it would destroy that experiment. It would set a fatal

precedent by which the minority could secede whenever it did not like what the

majority stood for until the United States fragmented into a dozen pitiful, squab-

bling countries, the laughing stock of the world. The successful establishment of

a slaveholding Confederacy would also enshrine the idea of inequality, a contra-

diction of the ideal of equal natural rights on which the United States was

founded.

“This issue embraces more than the fate of these United States,” said

Lincoln on another occasion. “It presents to the whole family of man, the

THE CIVIL WAR 429

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

question, whether a constitutional republic, or a democracy … can, or cannot,

maintain its territorial integrity. ’’ Nor is the struggle “altogether for today; it is

for a vast future…. On the side of the Union it is a struggle for maintaining in

the world that form and substance of government whose leading object is to

elevate the condition of men … to afford all an unfettered start, and a fair chance

in the race of life.”

To preserve the Union and maintain the republic: these verbs denote a con-

servative purpose. If the Confederacy’s war of independence was indeed a revo-

lution, Lincoln was most certainly a conservative. But if secession was an act of

counter-revolution to forestall a revolutionary threat to slavery posed by the

government Lincoln headed, these verbs take on a different meaning and

Lincoln’s intent to conserve the Union becomes something other than conserva-

tism. But precisely what it would become was not yet clear in 1861.

The second respect in which the Civil War is viewed as a revolution was in

its abolition of slavery. This was indeed a revolutionary achievement—not only

an expropriation of the principal form of property in half the country, but a de-

struction of the institution that was basic to the southern social order, the politi-

cal structure, the culture, the way of life in this region. But in 1861 this

revolutionary achievement was not part of Lincoln’s war aims.

From the beginning of the war, though, abolitionists and some Republicans

urged the Lincoln administration to turn the military conflict into a revolution-

ary crusade to abolish slavery and create a new order in the South. As one aboli-

tionist put it in 1861, although the Confederates “justify themselves under the

right of revolution,” their cause “is not a revolution but a rebellion against the

noblest of revolution.” The North must meet this southern counterrevolution by

converting the war for the Union into a revolution for freedom. “WE ARE

THE REVOLUTIONISTS,” he proclaimed. The principal defect of the first

American Revolution, in the eyes of abolitionists, had been that while it freed

white Americans from British rule it failed to free black Americans from slavery.

Now was the time to remedy that defect by proclaiming emancipation and

inviting the slaves “to a share in the glorious second American Revolution.” And

Thaddeus Stevens, the grim-visaged old gladiator who led the radical Republicans

in the House of Representatives, pulled no punches in this regard. “We must treat

this [war] as a radical revolution,” he declared, and “free every slave—slay every

traitor—burn every rebel mansion, if these things be necessary to preserve” the

nation.

Such words grated harshly on Lincoln’s ears durin g the first year of the

war. In his message to Congress in December 1861 the president deplored

the possibility that the war might “degenerate into a violent and remorseless

revolutionary struggle.” It was not that Lin coln wanted to preserve slavery. On

the contrary, he said many times: “I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not

wrong, nothi ng is wrong.”

But as president he could no t act officially on his

private “judgment [concerning] the mora l q uestion of slavery.” He was bound

by the Constitution, which protected the institution of slavery in the states. In

the first year of the war the North fought to preserve this Constitution and

restore the Union as it had existed before 1861. Lincoln’s theory of t he war

430 MAJOR PROBLEMS IN AMERICAN HISTORY

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

held that since secession was illegal, the Confederate states were still legally in

the Union although temporarily under the control of insurrectionists. The gov-

ernment’s purpose was t o suppress t his insurrection and restore loyal Unionists

to control of the southern states. The conflict was therefore a limited war with

the limited goal of restoring the status quo ante b ellum, not an unlimited war

to destroy an enemy nation and reshape its society. And s ince, in theory, the

southern states were still in the Union , they continued to enjoy all their con-

stitutional rights, including s lavery.

There were also several political reasons for Lincoln to take this conservative

position in 1861. For one thing, the four border slave states of Missouri, Ken-

tucky, Maryland, and Delaware had remained in the Union; Lincoln desperately

wanted to keep them there. He would like to have God on his side, Lincoln

supposedly said, but he must have Kentucky. In all of these four states except

Delaware a strong pro-Confederate faction existed. Any rash action by the

northern government against slavery, therefore, might push three more states

into the Confederacy. Moreover, in the North itself nearly half of the voters

were Democrats, who supported a war for the Union but might oppose a war

against slavery. For these reasons, Lincoln held at bay the Republicans and aboli-

tionists who were calling for an antislavery war and revoked actions by two of

his generals who had proclaimed emancipation by martial law in areas under

their command.

Antislavery Republicans challenged the theory underlying Lincoln’s concept

of a limited war. They pointed out that by 1862 the conflict had become in

theory as well as in fact a full-fledged war between nations, not just a police

action to suppress an uprising. By imposing a blockade on Confederate ports

and treating captured Confederate soldiers as prisoners of war rather than as

criminals or pirates, the Lincoln administration had in effect recognized that this

was a war rather than a mere domestic insurrection. Under international law,

belligerent powers had the right to seize or destroy enemy resources used to

wage war—munitions, ships, military equipment, even food for the armies and

crops sold to obtain cash to buy armaments. As the war escalated in scale and

fury and as Union armies invaded the South in 1861, they did destroy or capture

such resources. Willy-nilly the war was becoming a remorseless revolutionary

conflict, a total war rather than a limited one.

A major Confederate resource for waging war was the slave population,

which constituted a majority of the southern labor force. Slaves raised food for

the army, worked in war industries, built fortifications, dug trenches, drove army

supply wagons, and so on. As enemy property, these slaves were subject to con-

fiscation under the laws of war. The Union Congress passed limited confiscation

laws in August 1861 and July 1862 that authorized the seizure of this human

property. But pressure mounted during 1862 to go further than this—to pro-

claim emancipation as a means of winning the war by converting the slaves

from a vital war resource for the South to allies of the North, and beyond that

to make the abolition of slavery a goal of the war, in order to destroy the institu-

tion that had caused the war in the first place and would continue to plague the

nation in the future if it was allowed to survive. By the summer of 1861, most

THE CIVIL WAR 431

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Republicans wanted to turn this limited war to restore the old Union into a

revolutionary war to create a new nation purged of slavery.

For a time Lincoln tried to outflank this pressure by persuading the border

slave states remaining in the Union to undertake voluntary, gradual emancipa-

tion, with the owners to he compensated by the federal government. With

rather dubious reasoning, Lincoln predicted that such action would shorten the

war by depriving the Confederacy of its hope for the allegiance of these states

and thereby induce the South to give up the fight. And though the compensa-

tion of slaveholders would be expensive, it would cost much less than continuing

the war. If the border states adopted some plan of gradual emancipation such as

northern states had done after the Revolution of 1776, said Lincoln, the process

would not radically disrupt the social order.

Three times in the spring and summer of 1862 Lincoln appealed to con-

gressmen from the border states to endorse a plan for gradual emancipation. If

they did not, he warned in March, “it is impossible to foresee all the incidents

which may attend and all the ruin which may follow. ” In May he declared that

the changes produced by his gradual plan “would come gently as the dews of

heaven, not rending or wrecking anything. Will you not embrace it?… You

can not, if you would, be blind to the signs of the times.” But most of the

border-state representatives remained blind to the signs. They questioned the

constitutionality of Lincoln’s proposal, objected to its cost, bristled at its veiled

threat of federal coercion, and deplored the potential race problem they feared

would come with a large free black population. In July, Lincoln once more

called border-state congressmen to the White House. He admonished them

bluntly that “the unprecedentedly stern facts of the case” called for immediate

action. The limited war was becoming a total war; pressure to turn it into a

war of abolition was growing. The slaves were emancipating themselves by run-

ning away from home and coming into Union lines. If the border states did not

make “a decision at once to emancipate gradually … the institution in your states

will be extinguished by mere friction and abrasion—by the mere incidents of the

war.” In other words, if they did not accept an evolutionary plan for the aboli-

tion of slavery, it would he wiped out by the revolution that was coming. But

again they refused, rejecting Lincoln’s proposal by a vote of twenty to nine.

Angry and disillusioned, the president decided to embrace the revolution. That

very evening he made up his mind to issue an emancipation proclamation. After

a delay to wait for a Union victory, he sent forth the preliminary proclamation

on September 22—after the battle of Antietam—and the final proclamation on

New Year’s Day 1863.

The old cliché, that the proclamation did not free a single slave because it

applied only to the Confederate states where Lincoln had no power, completely

misses the point. The proclamation announced a revolutionary new war aim—

the overthrow of slavery by force of arms if and when Union armies conquered

the South. Of course, emancipation could not be irrevocably accomplished

without a constitutional amendment, so Lincoln threw his weight behind the

Thirteenth Amendment, which the House passed in January 1865. In the mean-

time two of the border states, Maryland and Missouri, which had refused to

432 MAJOR PROBLEMS IN AMERICAN HISTORY

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.