Brooking T. The History of New Zealand

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

4

The History of New Zealand

tions of steam and ash are seen from time to time. New Zealand's largest

city, Auckland in the north, is largely free of earthquake

risk—although

Rangitoto, the volcanic island in the city's Waitemata harbor, erupted as

recently as

1500.

Geological instability and frequent floods have not, however, bequeathed

great natural wealth to New Zealand. Unlike Australia it is not mineral-

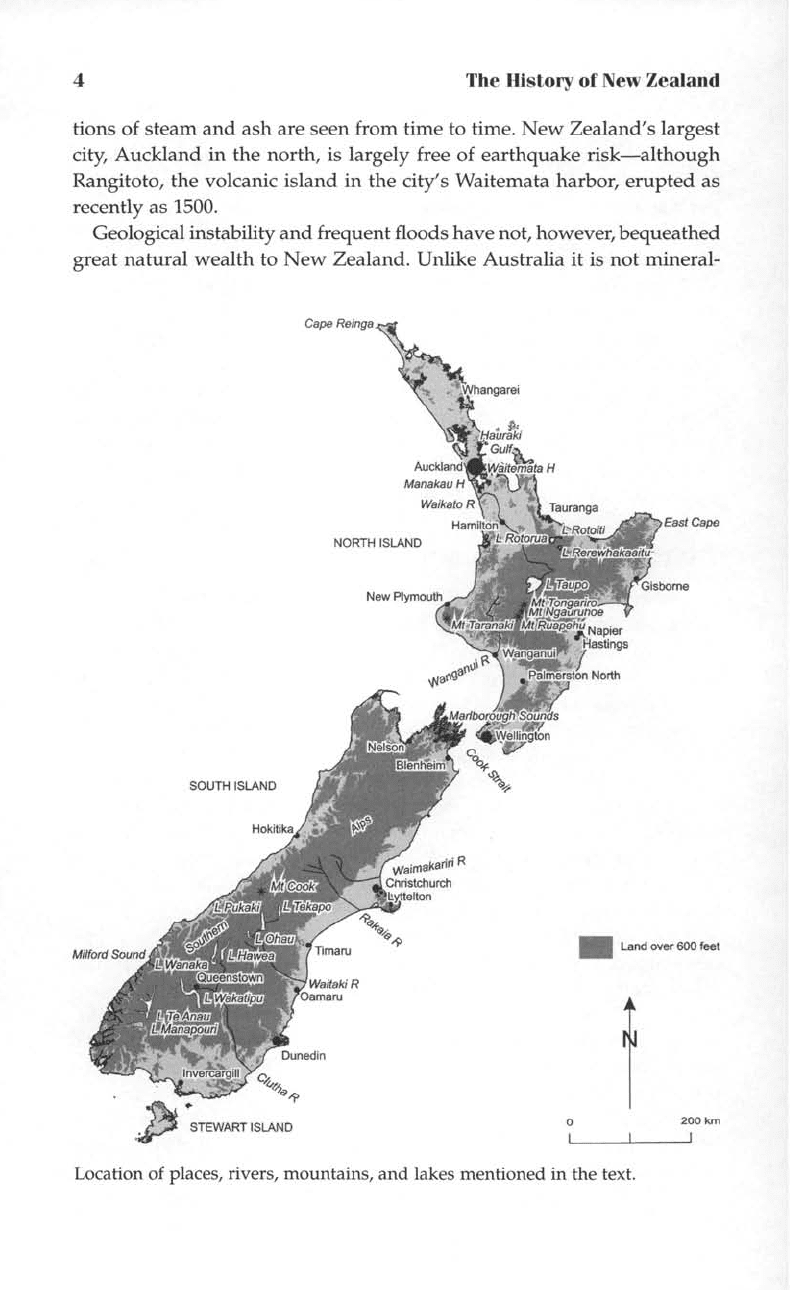

Location of places, rivers, mountains, and lakes mentioned in the text.

Geography, Environment, Peoples, and Government 5

rich. Enough gold lay buried to sustain a small gold rush in the nineteenth

century, and there is ample coal, but the vital industrial ingredient of iron

ore is missing. New Zealand does make steel today, but only by extracting

ore from the black sands of beaches on the west coast of the North Island.

Bauxite, used in the manufacture of aluminum, and uranium, which is

of such importance to the nuclear industry, are abundant in Australia

but absent from New Zealand. This dearth of mineral resources is com-

pounded by soils that are rather infertile. Native grasses that evolved over

countless millennia through interaction with large flightless birds failed

to provide adequate pasture for the cloven-hoofed grazing animals intro-

duced by European settlers. Consequently, they were replaced with English

grasses once the extensive rain forests had been removed by chopping

and burning. Although nineteenth-century migrants were lured by prom-

ises of rich soils, these exist only in pockets, and New Zealand is not

ideally suited to European-style stock and crop farming. The large flocks

of sheep and herds of dairy cows and domesticated deer that the tourist

views today all graze on soils whose fertility is enhanced with vast amounts

of artificial fertilizers and chemicals.

In short, New Zealand is a hard land transformed by massive human

effort—so

that today it presents the appearance of a neo-Europe rather

than an ancient piece of the old supercontinent of Gondwanaland. While

the southwestern corner of the country still looks much as it did in the

time of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago (which is why the BBC filmed

much of its Walking with Dinosaurs series there), most of the north and

east has been transformed more substantially and rapidly than any com-

parable country. Changes that took two millennia in Europe and four

centuries in North America have occurred in New Zealand in little over

a hundred years. The most extreme example is seen in the draining of

wetlands. New Zealand has removed some 85 percent of these areas, as

against 60 percent in Great Britain and the Netherlands, 53 percent in the

United States, and 10 percent in France. These swamplands were impor-

tant places of food-gathering for Maori and were often appropriated by

force, or the application of law, before conversion to dairy and sheep

farms.

IMMIGRANT MIX

American visitors also notice that New Zealanders are much less eth-

nically diverse than the population of the United States. In appearance

and cultural style, New Zealanders are either Polynesian or British. Maori

now make up over 15 percent of the population, and Pacific Islanders,

6

The History of New Zealand

mainly from Western Samoa, over 5 percent. By 2020 these two groups

will constitute over a quarter and 10 percent of the population respec-

tively. Asians represent a third major non-European

grouping—as

in, say,

the Pacific northwest of the United

States—and

in 2020 are predicted to

make up about 15 percent of the population.

European New Zealanders, who will become a minority before 2040,

are still largely Anglo-Celtic in origin. Indeed, New Zealand is the most

Anglo-Celtic of any of the New World countries. In the nineteenth century

settlers from Britain made up 96 percent of white migrants. Other Euro-

peans,

largely Scandinavians, Germans, and Croatians, made up the rest.

This resembled settlement patterns in Australia, except that Scots were

more important in New Zealand and the Irish less important. Scots made

up about 21 percent of nineteenth-century immigrants compared with 12

percent of Australia's migrants before 1900. The Irish made up 18 per-

cent—although

the 4 percent of total immigrants who were Presbyterians

from Northern Ireland could be regarded as more akin to the Scots. The

southern Irish, who made up around a quarter of Australia's migrants,

only represented a conspicuous Catholic minority of 14 percent in her

smaller neighbor. The remainder of the European population was En-

glish—but

if we separate the 9 percent of migrants from Cornwall, there

is a good case for labeling the nineteenth-century New Zealand migrant

mix Celtic-Anglo. Nevertheless, the English, predominantly from the south

and west, still constituted the single biggest group. New Zealand diverged

from Australia after the Second World War when it continued this essen-

tially British pattern (with the addition of a few Dutch), while Australia

opened its borders to a large inflow of southern Europeans. It is easy,

therefore, to detect American students taking courses in New Zealand

because so many of their names are German, Scandinavian, Polish, Italian,

and

Ukrainian—rather

than English, Scots, Irish, or Polynesian.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND POLITICAL SYSTEMS

New Zealand is not a republic but a member of the British Common-

wealth. American history students studying in New Zealand are often

surprised that, until relatively recently, New Zealanders were enthusiastic

members of the Commonwealth and, before 1947, the British Empire.

Should New Zealand ever become a republic, its Maori "rebels" could be

reinvented as

heroes—but

this should not disguise the fact that before the

1970s the new nation maintained a staunchly pro-British stance. However,

it was more an unshakeable belief in representative and responsible gov-

Geography, Environment, Peoples, and Government 7

ernment by early colonists in the 1850s, similar to their counterparts in

the

13

American colonies some 80 years earlier, that helped to bring about

a parliamentary democracy in New Zealand only 12 years into the col-

ony's existence.

The original Crown Colony Government, bestowed on New Zealand

once sovereignty had been acquired from the reigning Maori chiefs through

the Treaty of Waitangi in

1840,

gave the governor, appointed by the British

monarch, full control. Settlers were dismayed that in this new country

they had no say in the laws passed by the governor and his nominated

legislative council. By 1852, after considerable agitation for change, the

young colony was granted representative government through an act

passed by the British Parliament, which is still the basis of government in

the country today, albeit with several important changes. The original

Constitution Act created a bicameral arrangement similar to some of the

constitutions adopted by the 13 states of America in the

1770s

and

1780s.

The executive power rested with a governor, and the legislative council

was nominated by him. This upper house was abolished almost a century

later. However, the lower house was elected and remains today, still

known as the House of Representatives. A relatively wide franchise en-

abled men over 21 years of age who owned land worth £50 or who leased

land at an annual rental of £10 or more to vote. This limitation fell short

of the full manhood suffrage of Victoria in Australia but was still much

broader than most places at the time, including Britain. Maori males were

effectively excluded by the property-owning requirement, since land re-

maining in Maori hands was traditionally owned collectively by tribes or

subtribes. However, after 1853 more and more Maori males had their

shares in communally-owned property transferred to private ownership

and became eligible to vote. The white settler government was able to

limit their potential influence by granting all Maori men over 21 years of

age the right to vote, but only for four Maori seats. This was grossly dis-

proportionate to the number of Maori people in the colony. At the same

rate of representation enjoyed by non-Maori people, Maori people would

have been entitled to 16 seats. The measure was supposed to have lasted

only five years, but it was extended, and made indefinite in 1876. Today

the same four seats exist although, since 1975, Maori voters have had the

option of voting either for these seats or for the general electorates. Maori

were also disadvantaged in other constitutional ways. The secret ballot

was introduced in 1870, but not for Maori voters, who had to wait until

1937 for the same reform. Enrollment for voting became compulsory for

non-Maori, or Pakeha, voters in 1927 but not for Maori voters until 1956.

8

The History of New Zealand

An electoral roll had existed for Pakeha voters since 1854 but there was

no provision for a Maori roll until 1942, and the first one was not com-

pleted until 1949.

Such inequities were able to happen because in the 1860s the British

Colonial Office had handed control of "native affairs" over to the settler

government. At this time the members of parliament were mostly wealth-

ier farmers or businessmen who had an agenda to shift as much land in

the North Island from Maori ownership to settler ownership (virtually the

entire South Island had already been "purchased" by fair means or foul

by 1860) and the North Island offered areas that were amongst the most

fertile land in the world, particularly in Taranaki on the western coast, the

Waikato south of Auckland, and the aptly named Bay of Plenty to the east.

Not surprisingly, these were the three areas where war broke about be-

tween Maori people, reluctant to sell, and settlers on a mission to buy or

acquire at all costs. The guerrilla phase of this conflict dragged on until

1872.

In the original 1852 Constitution Act there was a provision for six pro-

vincial governments, in addition to the bicameral parliament based in

Auckland. These were seen as necessary because of the geographical spread

of the country. However, improvements in communications, particularly

the rapid growth of railways, made the provincial councils unnecessary,

and they were abolished in

1876.

Their demise meant that central govern-

ment and its state bureaucracy came to play a greater part in New Zea-

land's development than in most New World societies, but the relatively

small population in New Zealand was never going to support a "state"

government system as that in Australia and the United States.

The fledgling unitary government entrenched its hold by deciding

against federal union with Australia in 1890 and

1901—the

electorate ac-

cepted the politicians' argument that the great distances involved would

make it impractical of New Zealand to become the seventh state of Aus-

tralia. Both in 1890 and 1901 New Zealand ranked as the third-biggest

Australasian colony (after New South Wales and Victoria), and its capital,

Wellington, lay closer to the eastern Australian coast than did Perth in

Western Australia. Regardless, successive New Zealand governments de-

cided that the nation was big enough and sufficiently different culturally

and historically to go it alone. Some historians see this decision as a mis-

take,

but the experience of smaller states within the Australian union, such

as Tasmania, suggests that the country would have struggled to secure its

fair share of expenditure. More importantly, the decision to stay separate

pushed new Zealand towards a different historical trajectory and ce-

mented its independent character.

Geography, Environment, Peoples, and Government 9

In

1889,

all adult males were granted the vote; and all women won the

franchise in 1893, although Maori women were, like their male counter-

parts,

limited to voting for only four representatives. New Zealand beat

South Australia by one year as the first largely self-governing colony to

give women the vote. As a result it can lay claim to be the world's oldest

full democracy, albeit an imperfect one due to the differences in partici-

pation remaining between the Maori and Pakeha. Full statehood was fi-

nally secured under the Statute of Westminster in

1947

after New Zealand

had played a key role in securing small nations a voice within the new

United Nations organization. The Upper House was abolished soon after,

in 1951 by a supposedly conservative government on the grounds of cost.

As a result the executive

branch—the

cabinet of the government in

office—

assumed even greater powers than before. The New Zealand Supreme

Court had never assumed the role of counterweight to the power of the

executive branch as in the United States, and a very limited Bill of Rights

was enacted only as recently as 1990.

Much to the surprise of older citizens in New Zealand and the rest of

the world, in a referendum held in 1993 New Zealand abandoned the

"first past the post" system inherited from Westminster and used in all

general elections. As a result, since 1996 New Zealand has employed the

West German system of Mixed Member Proportional representation

(MMP). Under this system only half of the

120-strong

House of Repre-

sentatives is selected by the electorate, with the other 60 members elected

as "list" MPs depending on the size of party votes. To be represented in

parliament, a party must score at least 5 percent of the total party

vote—

a safeguard designed to avoid the chronic instability of countries like Italy

and Israel. It is too soon to say how well the change has worked, or to

predict whether it will survive. But it clearly reflects an attempt by the

electorate to reduce executive power and secure a parliament that is more

representative of the total electorate than parliaments elected under the

old two-party

system—Labor

and National being the New Zealand equiv-

alents of Democrats and Republicans in the United States.

GENDER AND RACE RELATIONS

The shape of both gender and race relations developed differently in

New Zealand than in other comparable countries. Paradoxically, the early

achievement of full female suffrage may have slowed the struggle for

greater equality for women by removing the need for ongoing campaign-

ing as occurred in both the United States and Great Britain. Nevertheless,

feminists in New Zealand have been determinedly active since the

1880s.

10

The History of New Zealand

Second-wave feminism added new impetus to reform in the 1970s, and

today women occupy a more prominent place in New Zealand public life

than anywhere else in the New World outside the United States. Scandi-

navian countries may have granted more rights to women, but in 2003

New Zealand has a woman prime minister (our second in succession),

governor-general, and chief

justice—and,

perhaps most remarkably, the

nation's second biggest corporation (Telecom) is headed by a woman.

Women have also made huge inroads into the medical and legal profes-

sions and now outnumber men in all university courses outside commerce

and engineering. Despite these advances, women are still economically

more vulnerable than men, suffer unacceptable levels of physical violence

and abuse, and have a low profile in big business; yet there is no doubt

that they hold a stronger position in New Zealand society than do their

Australian sisters.

Race relations in New Zealand are even more complex than gender

relations. Although Maori have made tangible gains over the last century,

their advances have proved much more modest than those enjoyed by

women. Nevertheless, along with their Pacific Island cousins, the cultural

contribution of Maori in the twentieth century has prevented New Zea-

land from becoming a kind of southern

Britain—as

tourists discover on

arrival in Auckland, the world's biggest Polynesian city. Maori subverted

and resisted the British imperial project from the beginning of contact,

initially by offering stiff military resistance and later by passive resistance.

More recently, the vibrancy of Maori culture has helped force legal rec-

ognition of grievances, especially through the Waitangi Tribunal process

discussed in chapter 9.

Although New Zealand has experienced high levels of intermarriage,

this has failed to resolve major health problems experienced by Maori or

close the gap in economic and educational achievement. Although Maori

fare better than indigenous Australians, New Zealanders must still deal

with alarming statistics that point to areas of severe disadvantage. Maori

women, for example, suffer the highest level of lung cancer in the world.

Gross overrepresentation in prisons, high crime levels, and unacceptable

school dropout rates all suggest trouble ahead unless the underlying is-

sues are addressed promptly. Maori and Pacific Islanders, who urbanized

very fast over little more than a generation after the Second World War,

still form something of an underclass in the larger cities. Even when al-

lowance is made for outstanding contributions in sports, music, and art

and the visibility of Maori protocol and ceremony on major public occa-

sions,

a great deal of effort and reconciliation is required if New Zealand

is to overcome the negative legacies of its colonial past.

2

Eastern Polynesians

become Maori

ARRIVAL

The consensus among prehistorians is that Maori arrived in New Zealand

about 800 years ago, around 1180

A.D.

A few scholars still opt for an earlier

date of arrival, but claims of longer occupation are increasingly dismissed

as eccentric. There is much less agreement about where Maori migrated

from, and Maori traditions about their origins were unhelpfully couched

in mythological terms. When British explorer Captain James Cook visited

New Zealand in

1769,

Maori replied to questions about their origins by

pointing to the sky and tracing their

whakapapa,

or genealogy, from Rangi,

the sky father, and Papatuanuku, the earth mother. Scholars agree that

groups of migrants from Southeast Asia began long sea voyages around

the Pacific as long as 3,000 years ago. Although New Zealand was the last

major settlement made by east Polynesians, their jumping-off point re-

mains unclear. Some scholars, particularly linguists, argue for the Mar-

quesas, while others suggest the Society Islands. The closer Cook Islands,

however, seem a much more logical place of embarkation because of the

hardships involved in long sea voyages in chilly waters. The case remains

open.

We do know, however, that Maori voyaged to New Zealand quite de-

12

The History of New Zealand

liberately in large, double-hulled, oceangoing waka, or canoes. The sug-

gestion made by historian Andrew Sharp that they arrived by accidental

voyaging was disproved by explorer David Lewis, who undertook a voy-

age of his own using traditional Polynesian methods involving long-range

and accurate navigation against prevailing winds. Maori seafarers were

expert at reading the stars, following the flight paths of birds, and tracing

currents and wave patterns. They truly deserved the title, bestowed by

eminent Maori scholar Sir Peter Buck, of Vikings of the Sunrise. Polyne-

sian settlers voyaged to New Zealand deliberately, probably to escape war

and famine, like immigrants everywhere.

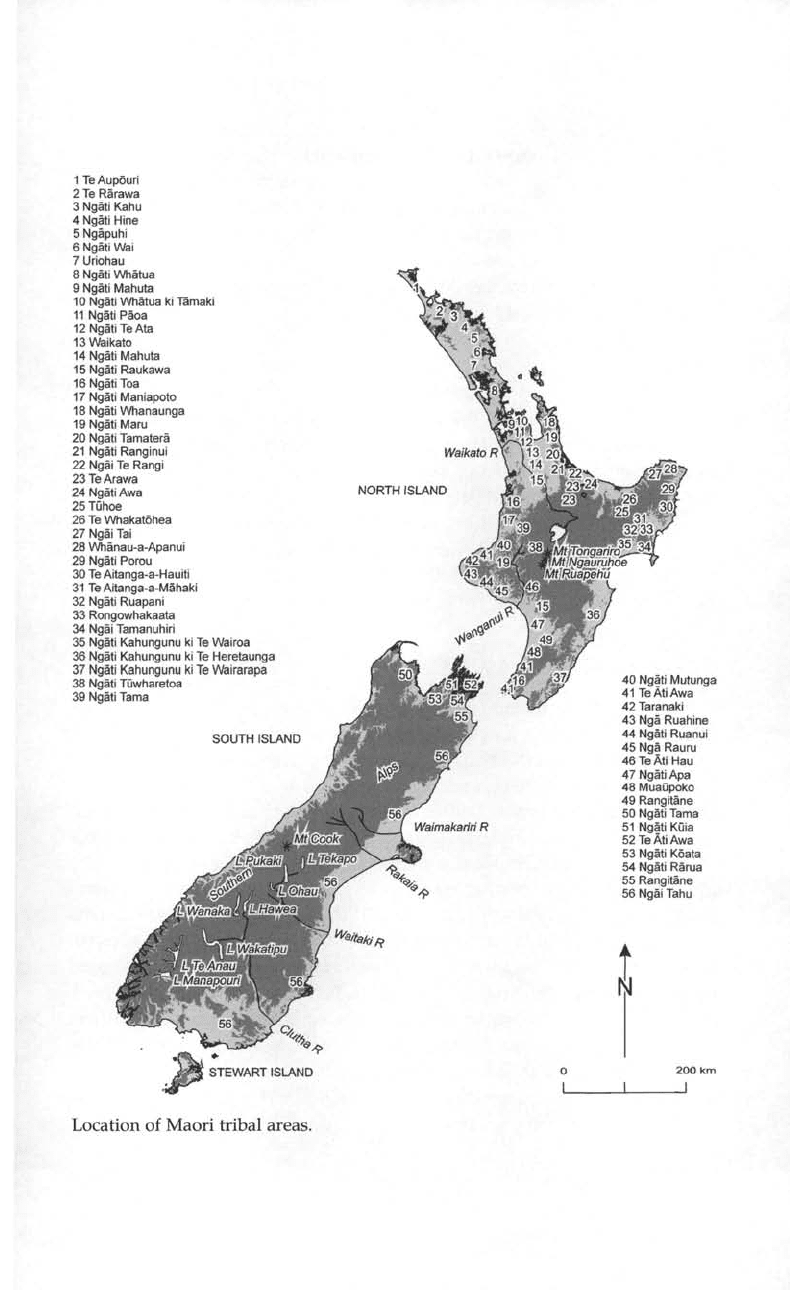

Several names for New Zealand survive in Maori tradition. The name

given to the land as a whole, Aotearoa, is often translated as land of the

long white

cloud—but

this reflects a romantic nineteenth-century con-

struction. Some scholars argue rather that Aotearoa means the land of

long daylight because tradition is consistent that Maori arrived in the

summer, and New Zealand has much longer evenings than tropical Poly-

nesia. Te

Ika

a Maui (the fish of

Maui—a

mythological demigod and

mischief-maker with supernatural powers) and Te Wai Pounamu or Wahi

Pounamau (the waters or place of greenstone, a type of jade) are probably

much older names for the North and South Islands respectively. When

considering these names for New Zealand as a whole, we should remem-

ber that Maori took a very tribal view of a country several times larger

than the whole of Polynesia put together.

The ancestors of Maori did not arrive in one great fleet in

1350—an

influential theory suggested by the late nineteenth-century ethnographer

Percy Smith. By reexamining Maori canoe traditions, scholars such as Da-

vid Simmons and Janet Davidson have shown that the immigrants arrived

intermittently, drifting south from the top of the North Island as earlier

arrivals took their pick of food resources in the mild climate of the far

north. These settlers were all eastern Polynesian; there is no evidence that

their arrival was preceded by pacifist peoples from elsewhere in the Pa-

cific,

as Smith, Edward Tregear, and other early investigators suggested.

These so-called Mori-ori were, in fact, nothing more than a myth invented

by these British-born ethnographers to justify British colonization of New

Zealand. Stories of great fleets and conquest of earlier peoples offered

remarkable similarities to the Norman conquest of England in

1066.

Little

wonder that this parallel history remained widely accepted within the

broader New Zealand community down to the 1990s. The Moriori did in

fact exist, but they were simply a group of eastern Polynesians who mi-

grated early (around 1350) to the Chatham Islands, about 500 miles east

of the South Island mainland. There, in a food-rich environment, a

rela-

1

Te

Aupouri

2 Te Rarawa

3 Ngati Kahu

4 Ngati Hine

5 Ngapuhi

6 Ngati Wai

7 Uriohau

8 Ngati Whatua

9 Ngati Mahuta

10 Ngati Whatua ki

Tamaki

11

Ngati Paoa

12

Ngati TeAta

13Waikato

14 Ngati Mahuta

15

Ngati

Raukawa

16 Ngati Toa

17 Ngati Maniapoto

18 Ngati Whanaunga

19 Ngati Maru

20 Ngati

Tamatera

21 Ngati Ranginui

22 Ngai Te Rangi

23 Te Arawa

24 Ngati Awa

25 Tuhoe

26 Te Whakatohea

27 Ngai Tai

28 Whanau-a-Apanui

29 Ngati Porou

30 Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti

31

Te

Aitanga-a-Mahaki

32 Ngati Ruapani

33 Rongowhakaata

34 Ngai

Tamanuhiri

35 Ngati Kahungunu ki Te

Watroa

36 Ngati Kahungunu ki Te Heretaunga

37 Ngati Kahungunu ki Te Wairarapa

38 Ngati Tuwharetoa

39 Ngati

Tama

40 Ngati Mutunga

41 Te

AtiAwa

42 Taranaki

43 Nga Ruahine

44 Ngati Ruanui

45 Nga Rauru

46TeAtiHau

47 Ngati Apa

48 Muaupoko

49 Rangitane

50 Ngati Tama

51 Ngati

Kuia

52 Te AtiAwa

53 Ngati

Koata

54 Ngati Rarua

55 Rangitane

56 Ngai Tahu

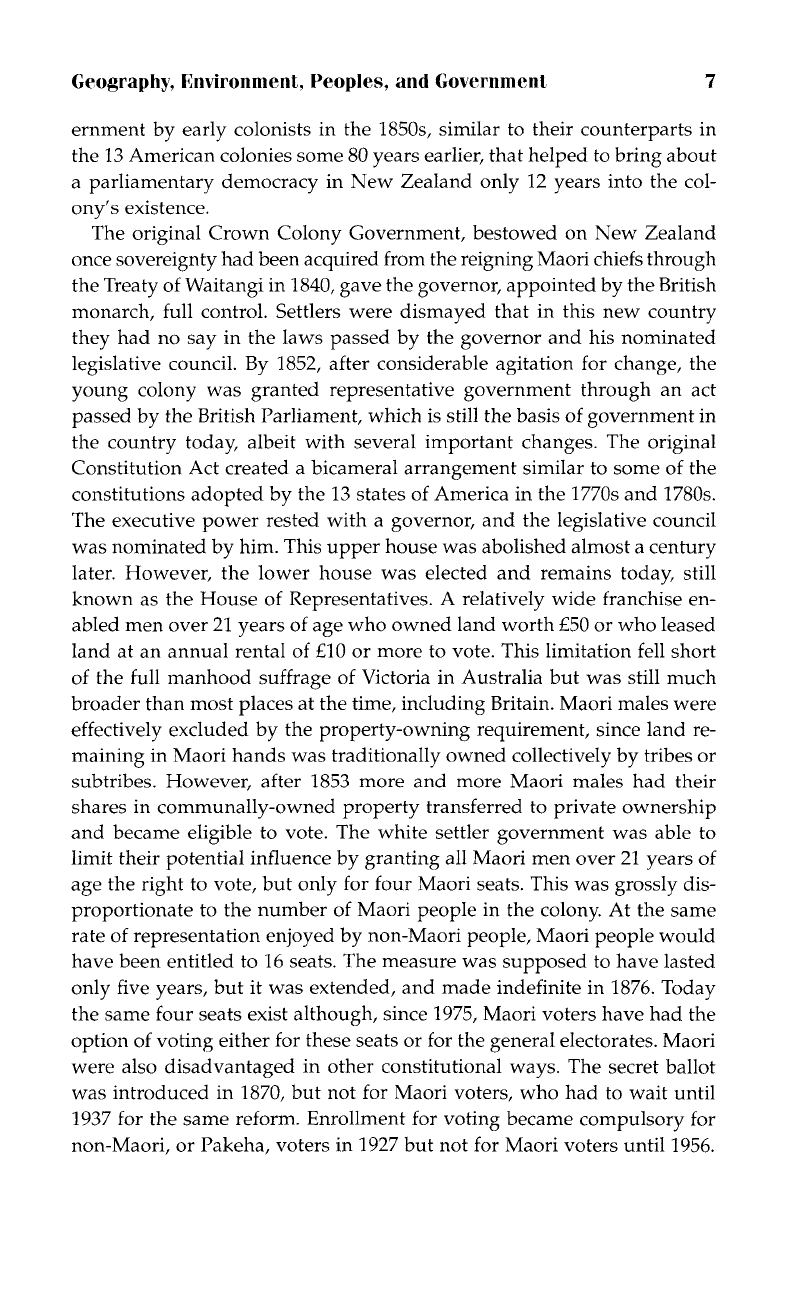

Location of Maori tribal areas.