Brooking T. The History of New Zealand

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

XXX

Timeline of Historical Events

population passes the 3 million mark, and New Zealand Au-

thor's Fund established.

1974 First oil shock. British people mandate their membership of

the EEC. Accident compensation scheme enacted. Second

television channel and color television introduced. Maori Af-

fairs Amendment Act tries to promote biculturalism. July 9,

Muldoon becomes leader of the National Party. August 31,

Norm Kirk dies. Wallace (Bill) Rowling takes over as prime

minister. September 21, franchise extended to 18 year olds.

1975

September to October, massive Maori land march to Welling-

ton. Waitangi Tribunal and Women's Electoral Lobby estab-

lished. November 29, Muldoon wins election for National by

23 seats.

1976 July 23, national superannuation scheme introduced at age

60.

Significant unemployment appears for the first time since

1938.

1977 February 19, Bruce Beethan wins a by-election for Social

Credit. Ngati Whatua protest development of tribal land at

Bastion Point in Auckland.

1978 May 25, massed police and army remove protestors from

Bastion Point. Eva Rickard occupies Raglan golf course. Sonja

Davies is the first women elected to the federation of labor

executive. Muldoon releases Think Big strategy for economic

development. Closer Economic Relations agreement proposed

with Australia. November 25, National's electoral majority

reduced to 11 seats.

1979 September 6, Gary Knapp wins for Social Credit in by-

election. Matui Rata forms the Mana Motuhake (Maori Sov-

ereignty) Party and breaks from Labor.

1980 Working Women's Charter passed by the Federation of Labor.

1981 Springbok rugby tour divides the nation. November

28,

Mul-

doon hangs on because of the support of provincial seats by

46 to Labor's 44 and Social Credit's 2. Mana Motuhake sec-

ond to Labor in the Maori electorates.

1982

Sue Wood becomes the first woman president of the National

or any other political party in New Zealand.

Timeline of Historical Events

xxxi

1983 February 3, David Lange replaces Rowling as leader of the

Labor Party.

1984 Unemployment soars toward 100,000. Entrepreneur Robert

Jones forms a free market New Zealand Party. July 14, Lange

leads Labor to victory by 19 seats at snap election. Exchange

and constitutional crisis follows immediately after the elec-

tion. Antinuclear policy implemented despite stiff American

and British opposition. Ann Hercus becomes the first min-

ister of women's affairs. Margaret Wilson becomes the first

woman president of the Labor Party. Donna Awatere pub-

lishes Maori Sovereignty. Te Maori exhibition opens in New

York.

1985

Labor moves to the right as the dollar is floated. Roger Doug-

las launches a program of corporatization of the civil service,

winds up tariffs, and opens the economy to the world. A

goods and services tax (GST) on all transactions introduced,

and the progressive rates lowered. July

10,

bombing of the

Rainbow

Warrior

by French frogmen in Auckland harbor. Wai-

tangi Tribunal given power to make recommendations on

land dealings back to 1840. Keri Hulme's The Bone People

wins the Booker (English literary) Prize.

1986 Free market reforms accelerated. August

16,

Te Maori Exhi-

bition opens in Wellington. December, the Homosexual Law

Reform Bill makes homosexuality legal.

1987 The Maori Council wins the right to stop Crown land being

transferred to the new state owned enterprises and Treaty of

Waitangi to apply to any such lands. This decision unleashes

an avalanche of new treaty claims over land grievances.

August-September, All Blacks win inaugural Rugby World

Cup.

October, share market crash. Lange lead Labor to elec-

toral victory over National's Jim McLay by 19 seats.

1988 Royal Commission on Social Policy reports arguing for tar-

geting of welfare. Gibb Report recommends more

business-

like approach to running the health system. Picot Report

recommends greater parent input into school governance.

1989

Reserve Bank Act passed to secure price stability by empow-

ering an independent governor to hold annual inflation un-

der 2 percent. GST raised from 10 to 12.5 percent. Post Bank

xxxii

Timeline of Historical Events

sold to the Australia New Zealand Bank. New Zealand Steel,

Coal Corp, and State Insurance privatized. School boards of

trustees meet for the first time. Sunday trading begins, and

third television channel begins broadcasting. Jim Anderton

leaves Labor to form the more left-leaning New Labor Party.

August 8, David Lange resigns as prime minister. Labor

moves right under Geoffrey Palmer. Bastion Point returned

to Ngati Whatua. Maori Fisheries Act grants 10 percent of

the fishery to Maori, and the Department of Maori Affairs

abolished. Its responsibilities devolved to Te Tira Ahu Iwi or

Iwi Transition Agency and new Manuta Maori (Ministry of

Maori Affairs) takes over policy advisory role.

1990 February, both Queen Elizabeth II and the Maori Bishop

Wharehuia Vercoe criticize New Zealand race relations at the

Sesquecentennial (150th) celebrations. Telecom sold to an

American-dominated overseas consortium. Limited Bill of

Rights passed. First volume of Dictionary of New Zealand Bi-

ography published. Palmer deposed and replaced by Mike

Moore as prime minister on September 4. Successful Com-

monwealth Games held in Auckland. National win a land-

slide election under new leader Jim Bolger by 37 seats. New

National government introduces welfare cuts in December.

National Congress of Tribes established.

1991 Welfare benefits cut further by over $1 billion. Unemploy-

ment passes 200,000, and inflation falls under 2 percent.

March, Winston Peters launches Ka Awatea (the new dawn)

and announces establishment of a Ministry of Maori Devel-

opment (Te Puni Kokiri). May, Employment Contracts Act

passed, abolishing compulsory unionism. August, Gilbert

Miles and

Hamish Mclntyre

leave National to form a new

Liberal Party, and New Zealand troops serve with the United

States in the Gulf War in Iraq. October, Winston Peters sacked

as minister of Maori affairs. December, New Labor, Mana

Motuhake, the Greens, and Democrats (old Social Credit) co-

alesce into the Alliance Party.

1992 January 1, Te Puni Kokiri commences operations, and Iwi

Transition Agency phased out two years early. New Zealand

wins seat on United Nations Security Council. August, Sea-

lord fisheries deal secured under Maori Fisheries Treaty of

Timeline of Historical Events

xxxiii

Waitangi Act. October, Peters dismissed from National party.

Regional Health Authorities and Crown Health Authorities

established to provide a funder/provider split in health ad-

ministration. University fees raised substantially, and loans

scheme at market rate of interest introduced. Fran Wild be-

comes the first woman to be elected mayor of a major met-

ropolitan center (Wellington).

1993 April, Peters wins by-election against his own party and

launches the New Zealand First Party in July. New Zealand

Rail sold to the Wisconsin Central Transport Company. Cen-

tenary of women's suffrage celebrated, and Dame Silvia

Cartwright becomes the first woman judge of the high court.

October, National hangs onto power once Labor's Peter Tap-

sell accepts the job of speaker of the house. The electorate

votes 53 to 47 percent in favor of a change of electoral system

from the old British first past the post to the West German

mixed member proportional representation (MMP). Jane

Campion's film The Piano wins international acclaim.

1994 May, New Zealand troops sent to Bosnia as peacekeepers.

Roger Douglas and Richard Prebble found the ACT (Asso-

ciation of Consumers and Taxpayers) Party. Treasury tries to

set a limit of $1 billion on treaty land grievance claims (the

so-called fiscal envelope). Unemployment starts to fall. Alan

Duff's novel Once Were

Warriors

is made into a movie, which

wins critical acclaim

1995 February, Waitangi Day celebrations canceled, and Ken Mair

occupies Motua Gardens in Wanganui. March Prime Minister

Bolger meets President Bill Clinton in the White House, the

first such meeting since

1984.

May, New Zealand wins Amer-

ica's Cup from American yachtsmen in San Diego. June,

United Party formed by seven breakaway MPs, four Na-

tional, and three Labor, led by

Clive

Matthewson. Christian

Heritage Party launched by Graham Lee. Broadcasting Cor-

poration of New Zealand private radio stations sold off. All

Maori reject fiscal envelope proposal, and in November Wai-

kato Raupatu Claims Settlement Act provides $187 million

and a government apology as reparations for the Tainui

tribes.

November, Commonwealth heads of government meet

in Auckland, and Nelson Mandela visits New Zealand.

xxxiv

Timeline of Historical Events

1996 April, Te Runanaga o Ngai Tahu Act establishes this iwi as a

full legal entity and $170 million pay in reparations by Oc-

tober. July, Danyon Loader wins New Zealand's first two

gold medals for swimming at the Olympics. August, Tara-

naki settlement condemns genocide practiced against Tara-

naki tribes and pays $145 million in reparations. Some 271

farms held on lease-in-perpetuity by Pakeha used as part of

the compensation. September, $40 million settlement offered

to Whakatohea tribe, but rejected. October, the first MMP

election produces a hung parliament with powerbroker Win-

ston Peters eventually siding with a National-led coalition

government.

1997 The National/New Zealand First Coalition wobbles under

pressure of the Asian financial crisis. December 8, Jenny

Ship-

ley replaces Bolger as National's leader after a bloodless coup

and become New Zealand's first woman prime minister.

1998 Shipley breaks up the coalition and hangs on with the sup-

port of

United's

Peter Dunne and the votes of the maverick

Alamein Kopu. A successful visit by President Clinton in late

1998

does little to shore up the coalition's declining fortunes.

1999 The Greens break from the Alliance, and Labor under Helen

Clark's leadership soars in popularity. Ongoing scandals and

declining economic indicators ensure that Labor wins com-

fortably and forms a coalition with the Alliance (Jim Ander-

ton serving as deputy prime minister) and general support

from the Greens, who won seven seats. This guarantees the

government 66 out of 120 votes within parliament. New Zea-

land retains the America's Cup.

2000 Millennium celebrations fail to produce a tourist boom, but

the steady as she goes policies of the new centrist govern-

ment are helped by high commodity prices. Despite constant

initial criticism by big business, the economy picks up. Dairy-

ing, especially, booms down to 2002, and growth climbs to 4

percent per annum.

2001 Unemployment drops to under 6 percent of the workforce,

and some New Zealanders begin to return from overseas.

September

11

hurts the New Zealand tourist industry, and

the government is forced to bail out Air New Zealand in

Timeline of Historical Events

xxxv

October. The crack

SAS

unit is sent to Afghanistan. Decem-

ber, first of Peter Jackson's film trilogy of The Lord of

the

Rings

launched to international critical acclaim and big audiences.

2002 The Alliance Party disintegrates, and Jim Anderton forms a

Progressive Coalition Party. Helen Clark decides to call an

early election in September and wins relatively easily with

41 percent of the vote, despite an emotional fallout with the

Greens over genetic engineering The socially conservative

United Futures Party does as well as the Greens, winning

8 seats, and forms a coalition with Labor and

Anderton's

2-seat party. The Greens with 9 seats generally support the

Labor coalition, giving it 62 safe votes and usually 71 votes

in parliament. National slumps to an all-time low of 21 per-

cent of the vote and 27 seats despite the best efforts of new

leader Bill English.

2003 The Iraq war and the SARS scare hurt the New Zealand econ-

omy, but the small nation remains relatively prosperous.

New Zealand refrains from supporting Australia, the United

States, and Britain in Iraq, but sends engineers to help with

reconstruction as it had done in East Timor and Afghanistan.

English and National continue to languish in the polls de-

spite several government mistakes. The electorate awaits the

end of the GMO moratorium in October with interest.

This page intentionally left blank

1

Geography,

Environment,

Peoples,

and Government

ISOLATION

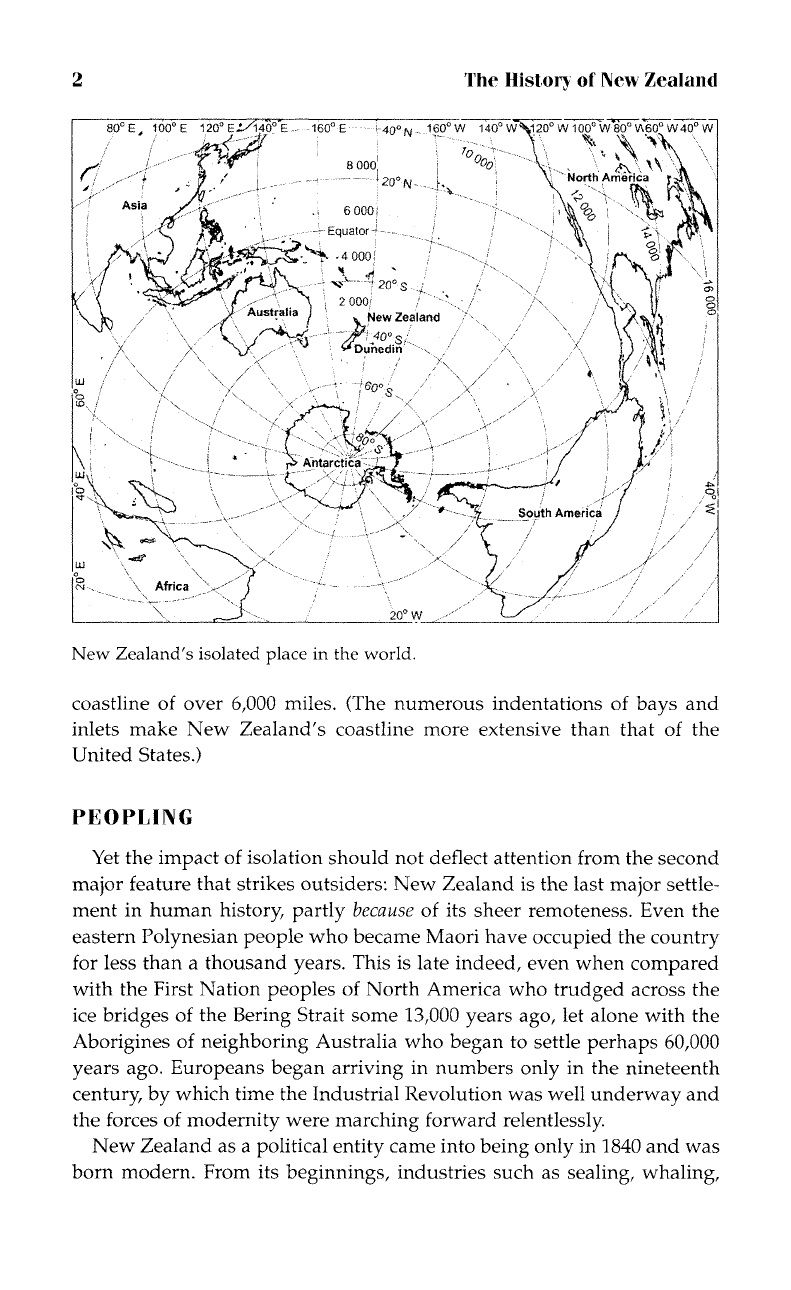

To the outsider, New Zealand's most distinctive feature is the country's

extraordinary isolation, or what the nineteenth-century English novelist

Anthony Trollope called "the feeling of awful distance." No other major

place of human settlement is situated so far from other large centers of

population. New Zealand's closest large neighbor is Australia some 1,200

miles

away—farther

than the distance from Los Angeles to Chicago, or

from New York to the Grand Canyon. The nearest continent is South

America, over 4,000 miles to the east, while Asia lies

5,000

miles to the

north, or over 10 hours' flying time away. Americans living in Alaska, the

remotest parts of the Midwest, or the Deep South are still much closer to

major centers of population. The role of distance is accentuated by the fact

that the largest group of settlers came from Britain, over 12,000 miles

away.

This extreme geographical isolation, coupled with a relatively small

population of 4 million, has made New Zealand particularly vulnerable

in terms of both economic development and defense. New Zealand has

had no option but to trade and has always been dependent on one of two

major world

powers—Britain

and the United

States—to

defend its long

2 The History of New Zealand

New Zealand's isolated place in the world.

coastline of over 6,000 miles. (The numerous indentations of bays and

inlets make New Zealand's coastline more extensive than that of the

United States.)

PEOPLING

Yet the impact of isolation should not deflect attention from the second

major feature that strikes outsiders: New Zealand is the last major settle-

ment in human history, partly because of its sheer remoteness. Even the

eastern Polynesian people who became Maori have occupied the country

for less than a thousand years. This is late indeed, even when compared

with the First Nation peoples of North America who trudged across the

ice bridges of the Bering Strait some

13,000

years ago, let alone with the

Aborigines of neighboring Australia who began to settle perhaps 60,000

years ago. Europeans began arriving in numbers only in the nineteenth

century, by which time the Industrial Revolution was well underway and

the forces of modernity were marching forward relentlessly.

New Zealand as a political entity came into being only in

1840

and was

born modern. From its beginnings, industries such as sealing, whaling,

Geography, Environment, Peoples, and Government 3

and timber milling locked it into the networks of global capitalism. Sailing

ships,

followed by steam ships, then airplanes, and from the 1960s jet

airliners have broken down what the Australian historian Geoffrey

Blai-

ney has called the "tyranny of distance." Connection to the international

cable system from 1876, the expansion of telephone services soon after,

the popularity of radio from the 1920s, then television after

1960,

and the

widespread use of the fax machine and Internet in the

1990s

have enabled

New Zealand to enjoy full and active membership in the global village.

As a result, today's visitor to New Zealand finds a country apparently

little different from many others in the developed world. Yet the distinc-

tive environment and history of this group of large and mountainous

islands covering 103,000 square miles (about the same area as Colorado)

and stretching over 1,000 miles from north to south (from subtropical 34

degrees to subarctic 47.5 degrees south) make any similarities rather su-

perficial.

ENVIRONMENT AND GEOGRAPHY

Less than a quarter of the New Zealand landmass lies below 650 feet,

and there are 253 named peaks over 7,000 feet tall. The Dutch explorer

Abel

Tasman

accurately labeled it "a land uplifted high." Extensive moun-

tain ranges drag down precipitation from the surrounding oceans to create

an unpredictable climate. In general terms, it is temperate (especially com-

pared with Britain or the northern United States) and lacks the freezing

winters and scorching summers of continental countries. But the weather

never locks into predictable patterns like those of southern California or

the Mediterranean, creating headaches for meteorologists. The country is

subject to bouts of severe flooding, while the so-called El Nino and La

Nina oscillation produces frequent droughts on the east coast and

snow-

storms in the

mountains—as

featured so vividly in Peter Jackson's movie

version of The Lord of the Rings.

These climatic hazards are amplified by geological instability. New Zea-

land straddles the large Pacific and

Indian-Australian

tectonic plates,

which are moving in opposite directions. Consequently, earthquakes oc-

cur regularly. Among the most destructive were those that leveled Wel-

lington in

1855

(now the capital city, but still a village when the earthquake

struck) and flattened the small cities of Napier and Hastings in

1931.

Strict

building codes and clever engineering initiatives have helped reduce the

risks of earthquake damage, but a large event is inevitable, especially in

Wellington, which like San Francisco is sited on a fault line. Three large

volcanoes in the central North Island are still active, and spectacular erup-