Banner A. The Calculus Lifesaver: All the Tools You Need to Excel at Calculus

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

216 • Inverse Functions and Inverse Trig Functions

10.2.4 Inverse secant

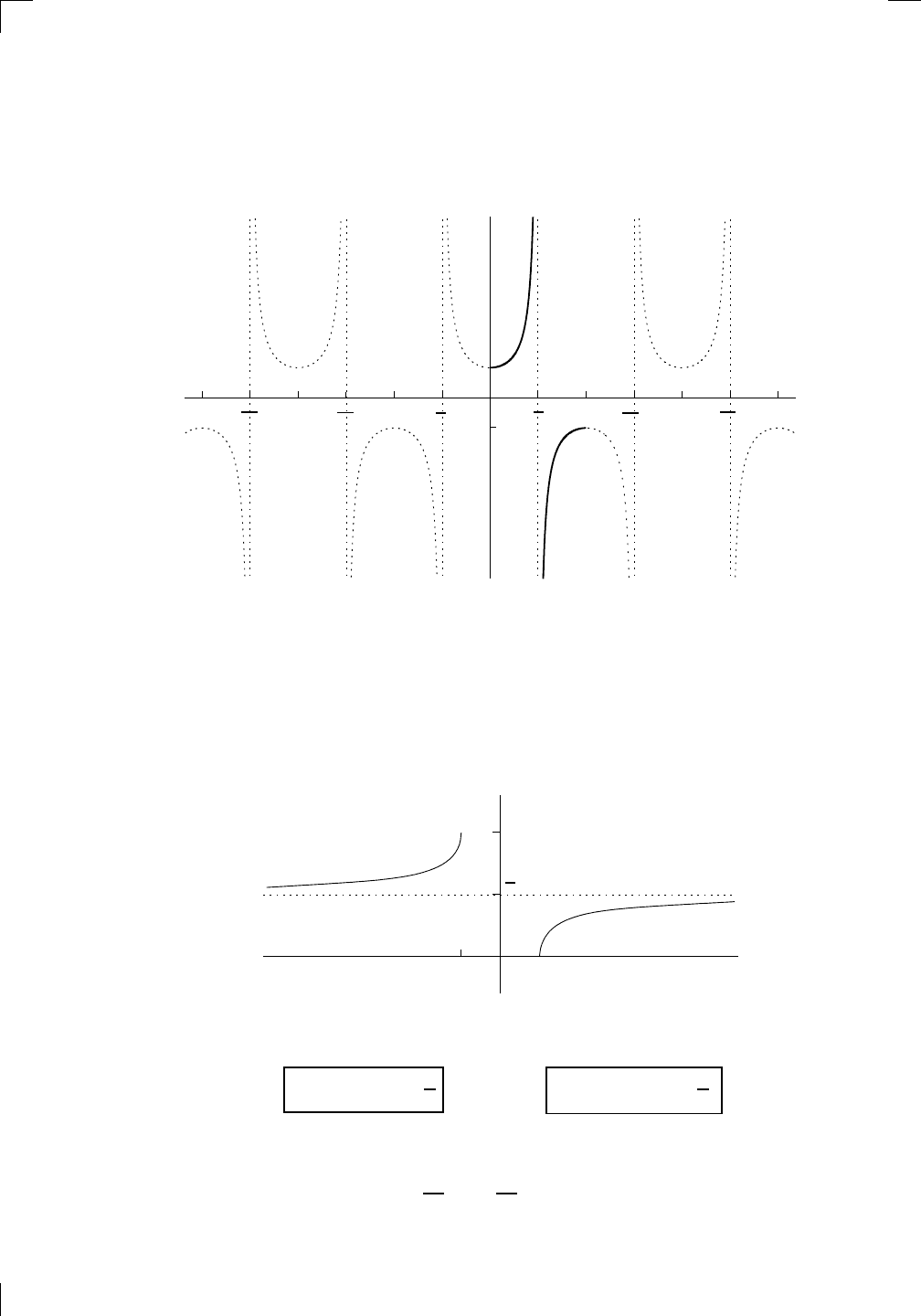

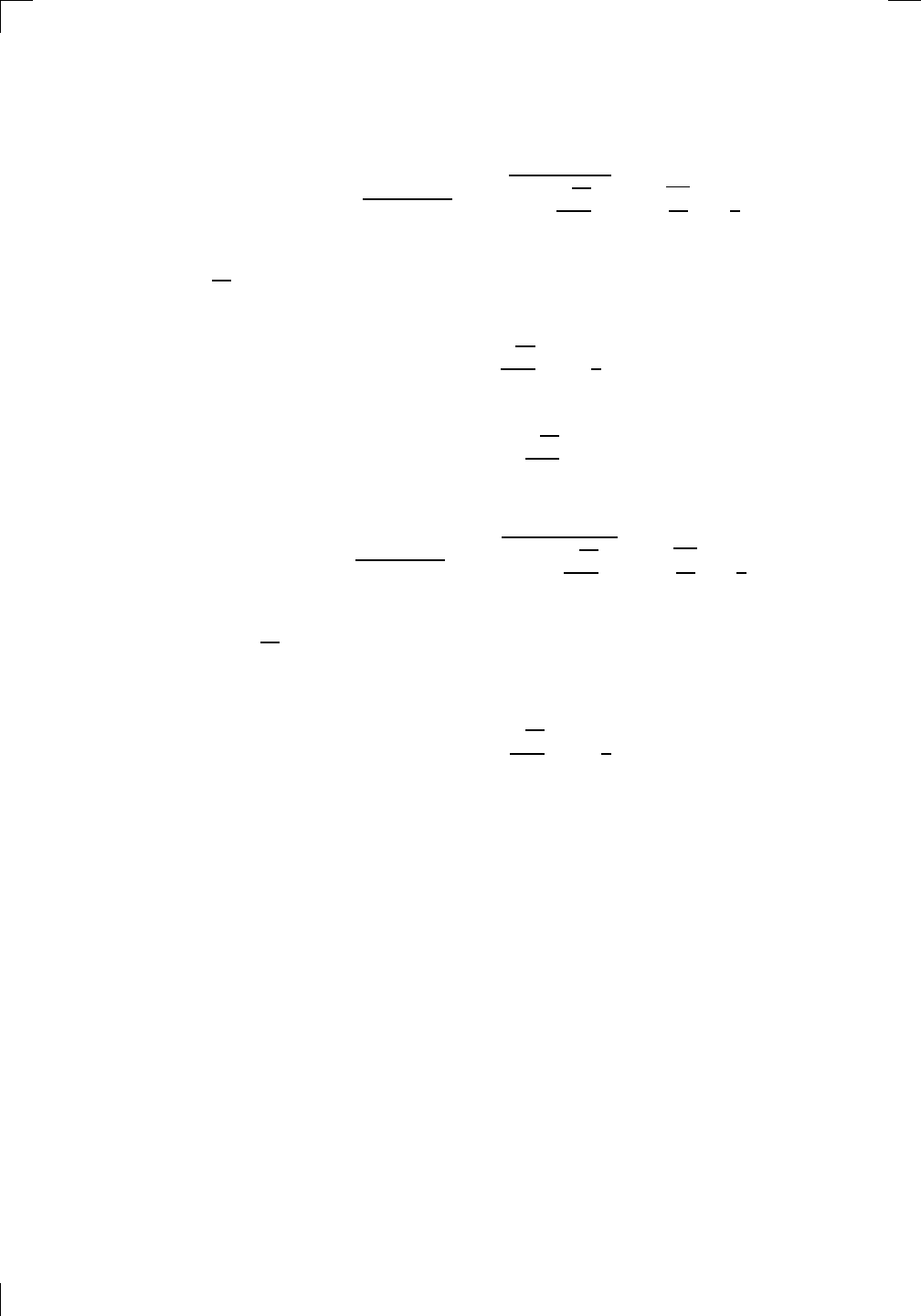

The saga continues. Here’s the graph of y = sec(x):

PSfrag replacements

(

a, b)

[

a, b]

(

a, b]

[

a, b)

(

a, ∞)

[

a, ∞)

(

−∞, b)

(

−∞, b]

(

−∞, ∞)

{

x : a < x < b}

{

x : a ≤ x ≤ b}

{

x : a < x ≤ b}

{

x : a ≤ x < b}

{

x : x ≥ a}

{

x : x > a}

{

x : x ≤ b}

{

x : x < b}

R

a

b

shadow

0

1

4

−

2

3

−

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

mirror (

y = x)

f

−

1

(x) =

3

√

x

y = h

(x)

y = h

−

1

(x)

y = (

x − 1)

2

−

1

x

Same height

−

x

Same length,

opposite signs

y = −

2x

−

2

1

y =

1

2

x − 1

2

−

1

y = 2

x

y = 10

x

y = 2

−

x

y = log

2

(

x)

4

3 units

mirror (

x-axis)

y = |

x|

y = |

log

2

(x)|

θ radians

θ units

30

◦

=

π

6

45

◦

=

π

4

60

◦

=

π

3

120

◦

=

2

π

3

135

◦

=

3

π

4

150

◦

=

5

π

6

90

◦

=

π

2

180

◦

= π

210

◦

=

7

π

6

225

◦

=

5

π

4

240

◦

=

4

π

3

270

◦

=

3

π

2

300

◦

=

5

π

3

315

◦

=

7

π

4

330

◦

=

11

π

6

0

◦

= 0 radians

θ

hypotenuse

opposite

adjacent

0 (

≡ 2π)

π

2

π

3

π

2

I

II

III

IV

θ

(

x, y)

x

y

r

7

π

6

reference angle

reference angle =

π

6

sin +

sin −

cos +

cos −

tan +

tan −

A

S

T

C

7

π

4

9

π

13

5

π

6

(this angle is

5

π

6

clockwise)

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(

x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(

x)

y = cos(

x)

−

π

2

π

2

y = tan(

x), −

π

2

< x <

π

2

0

−

π

2

π

2

y = tan(

x)

−

2π

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

y = sec(

x)

y = csc(

x)

y = cot(

x)

y = f(

x)

−

1

1

2

y = g(

x)

3

y = h

(x)

4

5

−

2

f(

x) =

1

x

g(

x) =

1

x

2

etc.

0

1

π

1

2

π

1

3

π

1

4

π

1

5

π

1

6

π

1

7

π

g(

x) = sin

1

x

1

0

−

1

L

10

100

200

y =

π

2

y = −

π

2

y = tan

−

1

(x)

π

2

π

y =

sin(

x)

x

, x > 3

0

1

−

1

a

L

f(

x) = x sin (1/x)

(0 < x < 0

.3)

h

(x) = x

g(

x) = −x

a

L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) DNE

M

}

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = M

lim

x

→a

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) DNE

y = f(

x)

a

y =

|

x|

x

1

−

1

y =

|

x + 2|

x + 2

1

−

1

−

2

1

2

3

4

a

a

b

y = x sin

1

x

y = x

y = −

x

a

b

c

d

C

a

b

c

d

−

1

0

1

2

3

time

y

t

u

(

t, f(t))

(

u, f(u))

time

y

t

u

y

x

(

x, f(x))

y = |

x|

(

z, f(z))

z

y = f(

x)

a

tangent at x = a

b

tangent at x = b

c

tangent at x = c

y = x

2

tangent

at x = −

1

u

v

uv

u + ∆

u

v + ∆

v

(

u + ∆u)(v + ∆v)

∆

u

∆

v

u

∆v

v∆

u

∆

u∆v

y = f(

x)

1

2

−

2

y = |

x

2

− 4|

y = x

2

− 4

y = −

2x + 5

y = g(

x)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

y = f(

x)

3

−

3

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

easy

hard

flat

y = f

0

(

x)

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

1

−

1

y = sin(

x)

y = x

x

A

B

O

1

C

D

sin(

x)

tan(

x)

y =

sin(

x)

x

π

2

π

1

−

1

x = 0

a = 0

x > 0

a > 0

x < 0

a < 0

rest position

+

−

y = x

2

sin

1

x

N

A

B

H

a

b

c

O

H

A

B

C

D

h

r

R

θ

1000

2000

α

β

p

h

y = g(

x) = log

b

(x)

y = f(

x) = b

x

y = e

x

5

10

1

2

3

4

0

−1

−2

−3

−4

y = ln(x)

y = cosh(x)

y = sinh(x)

y = tanh(x)

y = sech(x)

y = csch(x)

y = coth(x)

1

−1

y = f(x)

original function

inverse function

slope = 0 at (x, y)

slope is infinite at (y, x)

−108

2

5

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−1

−2

−3

−4

−5

−6

−3π

−

5π

2

−2π

−

3π

2

−π

−

π

2

3π

3π

5π

2

2π

3π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(x)

1

0

−1

−3π

−

5π

2

−2π

−

3π

2

−π

−

π

2

3π

5π

2

2π

2π

3π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(x)

y = sin(x), −

π

2

≤ x ≤

π

2

−2

−1

0

2

π

2

−

π

2

y = sin

−1

(x)

y = cos(x)

π

π

2

y = cos

−1

(x)

−

π

2

1

x

α

β

y = tan(x)

y = tan(x)

1

y = tan

−1

(x)

y = sec(x)

The situation is (unsurprisingly) very similar to the one we faced when we

inverted the cosine function. The domain has to be restricted to [0, π], except

for the point π/2, which isn’t even in the original domain of sec(x). The

range of secant is the union of the two intervals (−∞, −1] and [1, ∞), so this

becomes the domain of the inverse function sec

−1

(alternatively arcsec). As

for the range of sec

−1

, it’s the same as the restricted domain: [0, π] minus the

point π/2. The graph looks like this:

PSfrag replacements

(

a, b)

[

a, b]

(

a, b]

[

a, b)

(

a, ∞)

[

a, ∞)

(

−∞, b)

(

−∞, b]

(

−∞, ∞)

{

x : a < x < b}

{

x : a ≤ x ≤ b}

{

x : a < x ≤ b}

{

x : a ≤ x < b}

{

x : x ≥ a}

{

x : x > a}

{

x : x ≤ b}

{

x : x < b}

R

a

b

shadow

0

1

4

−

2

3

−

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

mirror (

y = x)

f

−

1

(x) =

3

√

x

y = h

(x)

y = h

−

1

(x)

y = (

x − 1)

2

−

1

x

Same height

−

x

Same length,

opposite signs

y = −

2x

−

2

1

y =

1

2

x − 1

2

−

1

y = 2

x

y = 10

x

y = 2

−

x

y = log

2

(

x)

4

3 units

mirror (

x-axis)

y = |

x|

y = |

log

2

(x)|

θ radians

θ units

30

◦

=

π

6

45

◦

=

π

4

60

◦

=

π

3

120

◦

=

2

π

3

135

◦

=

3

π

4

150

◦

=

5

π

6

90

◦

=

π

2

180

◦

= π

210

◦

=

7

π

6

225

◦

=

5

π

4

240

◦

=

4

π

3

270

◦

=

3

π

2

300

◦

=

5

π

3

315

◦

=

7

π

4

330

◦

=

11

π

6

0

◦

= 0 radians

θ

hypotenuse

opposite

adjacent

0 (

≡ 2π)

π

2

π

3

π

2

I

II

III

IV

θ

(

x, y)

x

y

r

7

π

6

reference angle

reference angle =

π

6

sin +

sin −

cos +

cos −

tan +

tan −

A

S

T

C

7

π

4

9

π

13

5

π

6

(this angle is

5

π

6

clockwise)

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(

x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(

x)

y = cos(

x)

−

π

2

π

2

y = tan(

x), −

π

2

< x <

π

2

0

−

π

2

π

2

y = tan(

x)

−

2π

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

y = sec(

x)

y = csc(

x)

y = cot(

x)

y = f(

x)

−

1

1

2

y = g(

x)

3

y = h

(x)

4

5

−

2

f(

x) =

1

x

g(

x) =

1

x

2

etc.

0

1

π

1

2

π

1

3

π

1

4

π

1

5

π

1

6

π

1

7

π

g(

x) = sin

1

x

1

0

−

1

L

10

100

200

y =

π

2

y = −

π

2

y = tan

−

1

(x)

π

2

π

y =

sin(

x)

x

, x > 3

0

1

−

1

a

L

f(

x) = x sin (1/x)

(0 < x < 0

.3)

h

(x) = x

g(

x) = −x

a

L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) DNE

M

}

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = M

lim

x

→a

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) DNE

y = f (

x)

a

y =

|

x|

x

1

−

1

y =

|

x + 2|

x + 2

1

−

1

−

2

1

2

3

4

a

a

b

y = x sin

1

x

y = x

y = −

x

a

b

c

d

C

a

b

c

d

−

1

0

1

2

3

time

y

t

u

(

t, f(t))

(

u, f(u))

time

y

t

u

y

x

(

x, f(x))

y = |

x|

(

z, f(z))

z

y = f(

x)

a

tangent at x = a

b

tangent at x = b

c

tangent at x = c

y = x

2

tangent

at x = −

1

u

v

uv

u + ∆

u

v + ∆

v

(

u + ∆u)(v + ∆v)

∆

u

∆

v

u

∆v

v∆

u

∆

u∆v

y = f(

x)

1

2

−

2

y = |

x

2

− 4|

y = x

2

− 4

y = −

2x + 5

y = g(

x)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

y = f (

x)

3

−

3

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

easy

hard

flat

y = f

0

(

x)

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

1

−

1

y = sin(

x)

y = x

x

A

B

O

1

C

D

sin(

x)

tan(

x)

y =

sin(

x)

x

π

2

π

1

−

1

x = 0

a = 0

x > 0

a > 0

x < 0

a < 0

rest position

+

−

y = x

2

sin

1

x

N

A

B

H

a

b

c

O

H

A

B

C

D

h

r

R

θ

1000

2000

α

β

p

h

y = g(x) = log

b

(x)

y = f(x) = b

x

y = e

x

5

10

1

2

3

4

0

−1

−2

−3

−4

y = ln(x)

y = cosh(x)

y = sinh(x)

y = tanh(x)

y = sech(x)

y = csch(x)

y = coth(x)

1

−1

y = f(x)

original function

inverse function

slope = 0 at (x, y)

slope is infinite at (y, x)

−108

2

5

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−1

−2

−3

−4

−5

−6

−3π

−

5π

2

−2π

−

3π

2

−π

−

π

2

3π

3π

5π

2

2π

3π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(x)

1

0

−1

−3π

−

5π

2

−2π

−

3π

2

−π

−

π

2

3π

5π

2

2π

2π

3π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(x)

y = sin(x), −

π

2

≤ x ≤

π

2

−2

−1 0

2

π

2

−

π

2

y = sin

−1

(x)

y = cos(x)

π

π

2

y = cos

−1

(x)

−

π

2

1

x

α

β

y = tan(x)

y = tan(x)

1

y = tan

−1

(x)

y = sec(x)

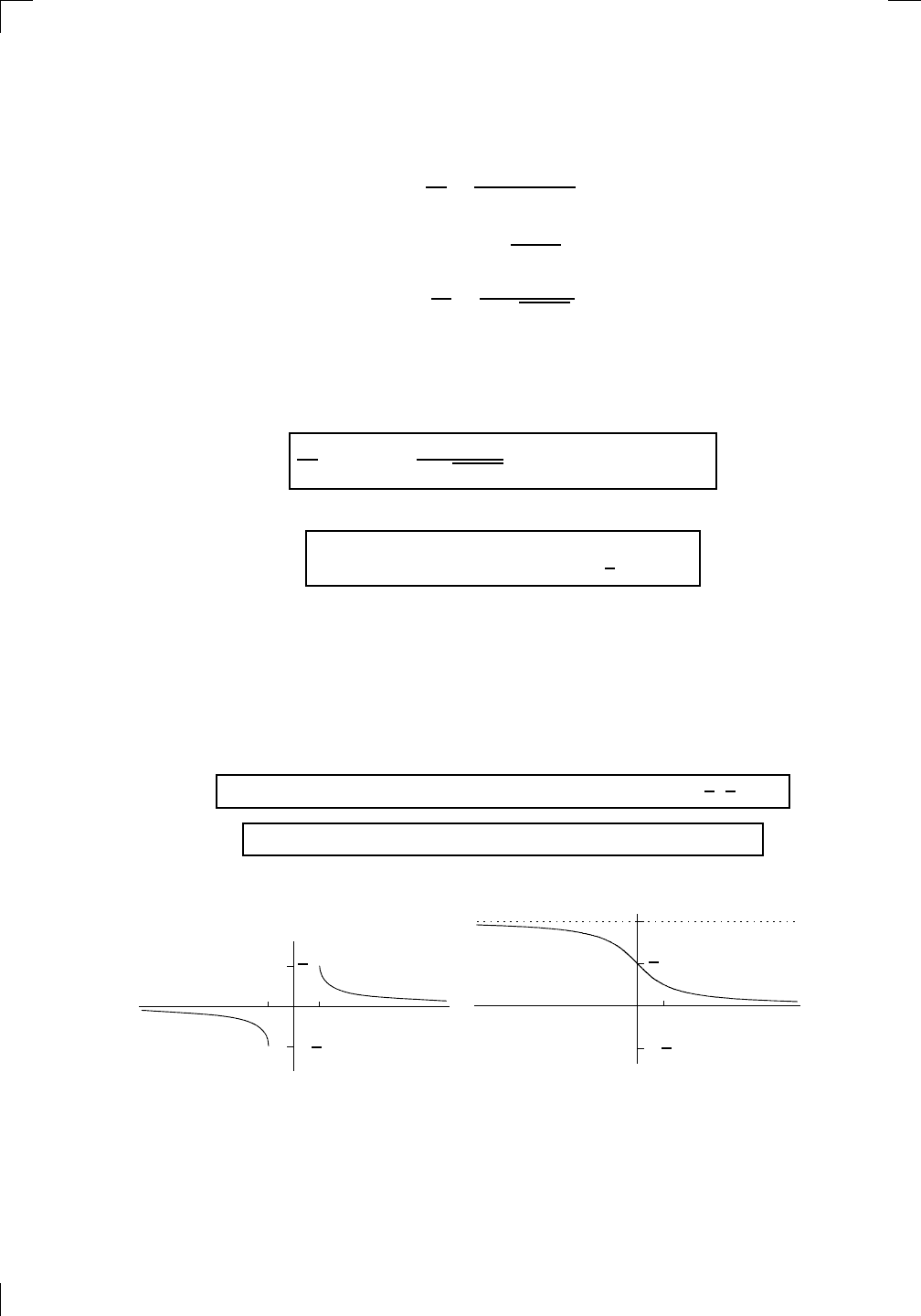

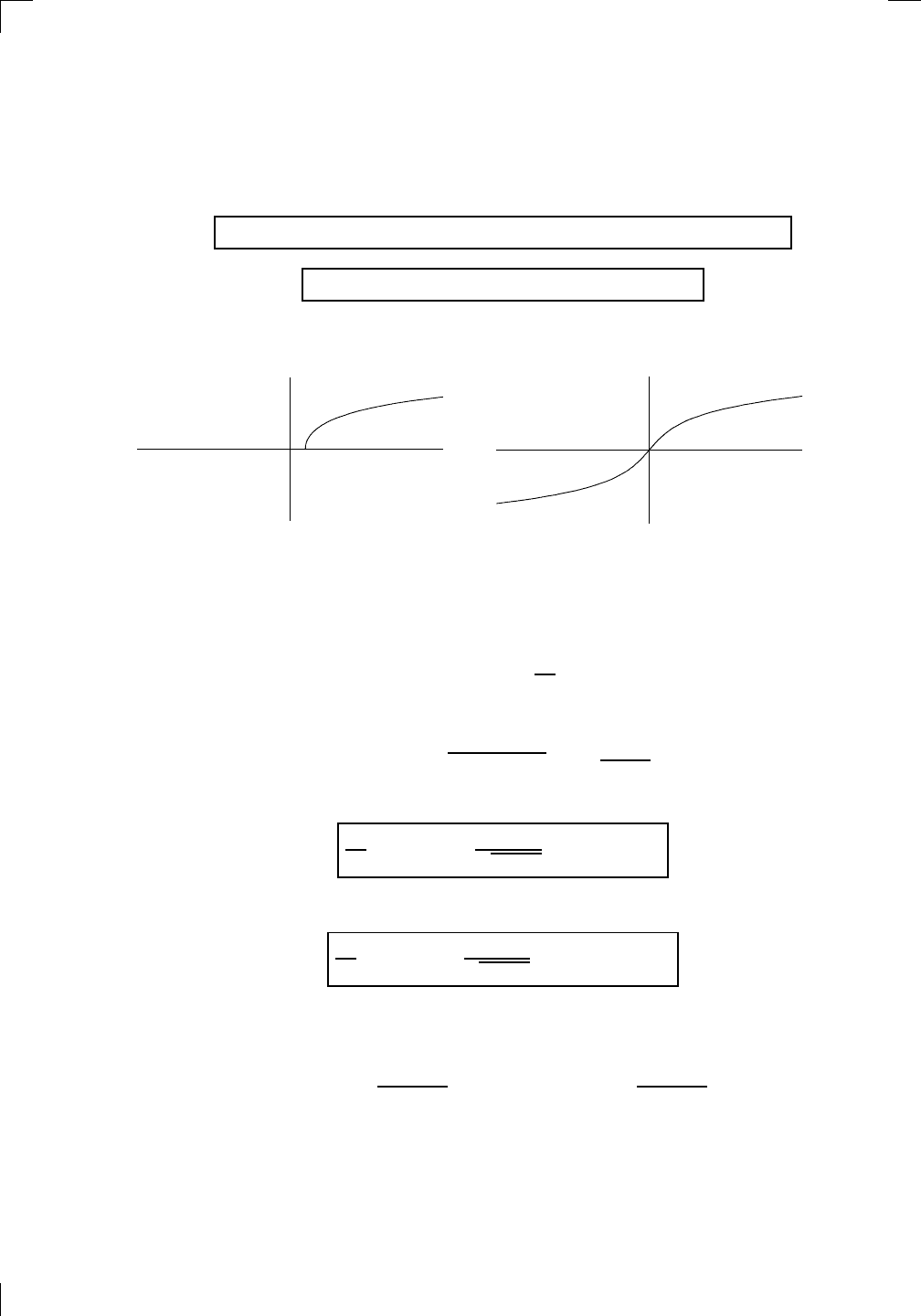

y = sec

−1

(x)

Note that there’s a two-sided horizontal asymptote at y = π/2, so

lim

x→∞

sec

−1

(x) =

π

2

and lim

x→−∞

sec

−1

(x) =

π

2

.

Let’s find the derivative. If y = sec

−1

(x) then x = sec(y), so

d

dx

(x) =

d

dx

(sec(y)).

Section 10.2.5: Inverse cosecant and inverse cotangent • 217

Make sure you see why this leads to

dy

dx

=

1

sec(y) tan(y)

.

Now x = sec(y), so since sec

2

(y) = 1 + tan

2

(y), we can rearrange and take

square roots to show that tan(y) = ±

√

x

2

− 1. This means that

dy

dx

=

1

±x

√

x

2

− 1.

Is it plus or minus? Looking at the graph of y = sec

−1

(x) above, you can

see that the slope is always positive. So in fact we need to be a little more

clever—instead of the plus or minus, we can simply put |x| instead of x and

we always get something positive. That is,

d

dx

sec

−1

(x) =

1

|x|

√

x

2

− 1

for x > 1 or x < −1.

We can summarize the other facts about inverse secant like this:

sec

−1

is neither odd nor even; it has domain

(−∞, −1] ∪ [1, ∞) and range [0, π]\{

π

2

}.

(Here I used the standard abbreviations of ∪ to mean the union of two inter-

vals, and \ to mean “not including.”)

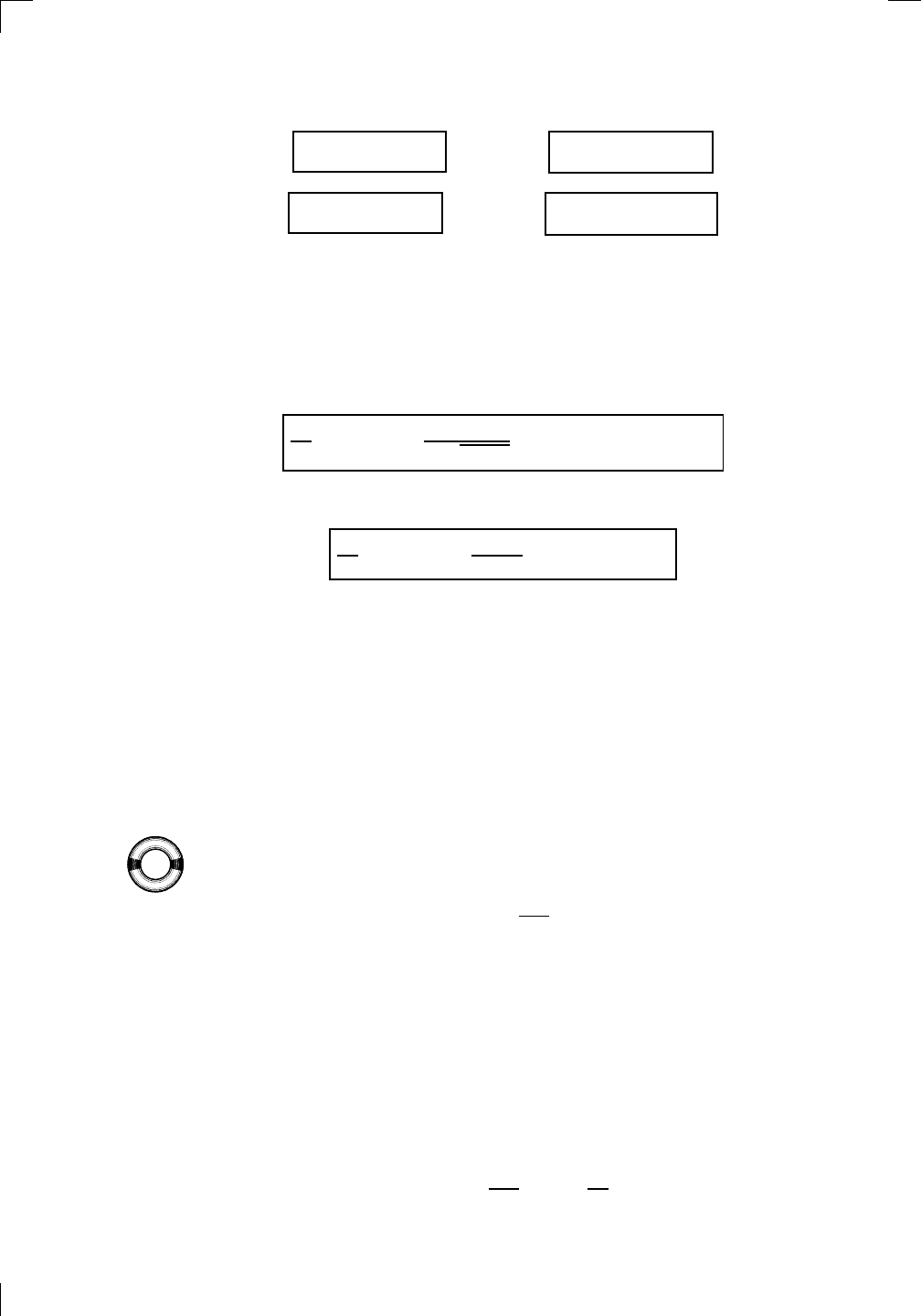

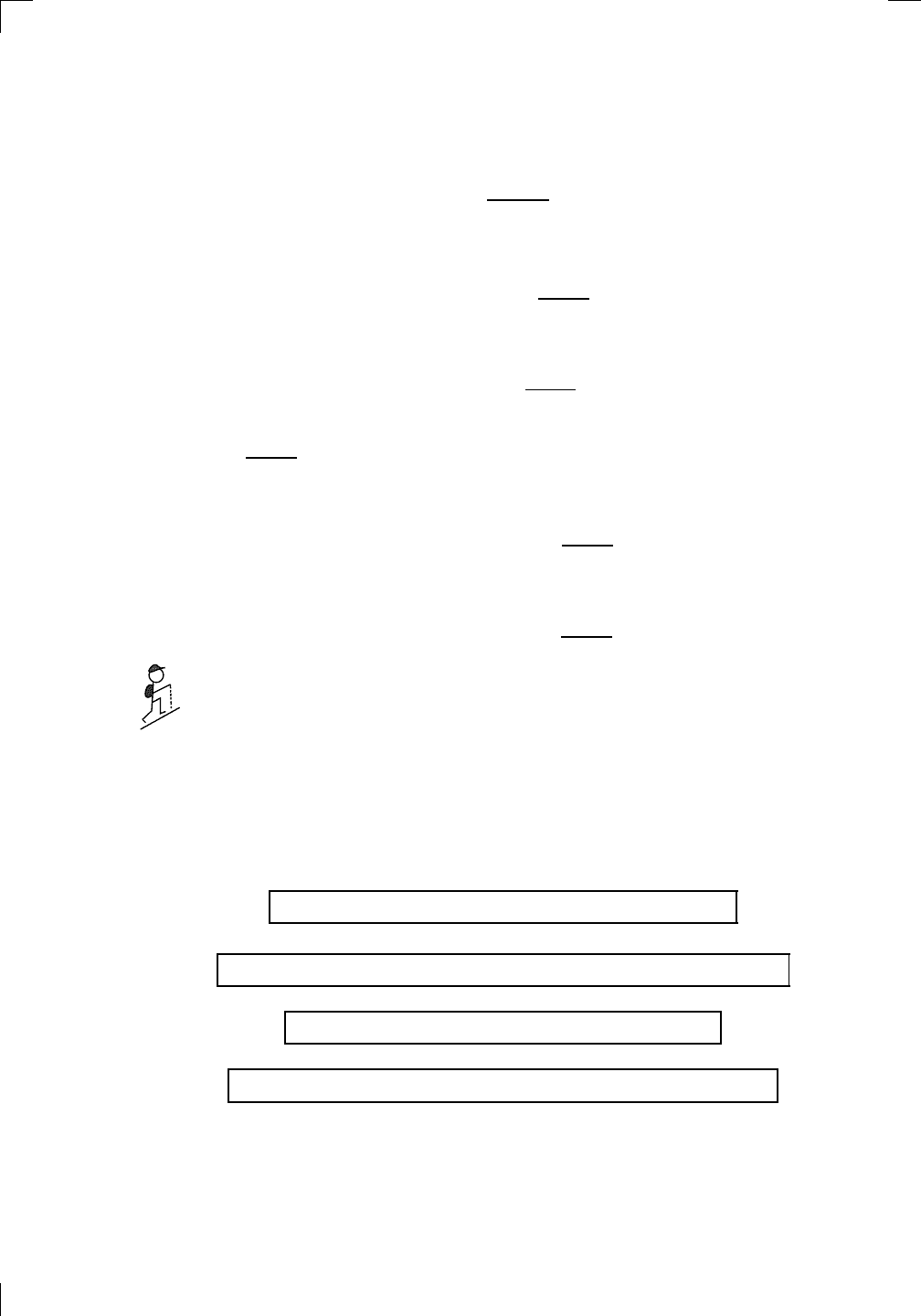

10.2.5 Inverse cosecant and inverse cotangent

Let’s just wrap the last two inverse trig functions up quickly. You can repeat

the above analyses to find the domain, range, and graphs of y = csc

−1

(x) and

y = cot

−1

(x):

csc

−1

is odd; it has domain (−∞, −1] ∪ [1, ∞) and range [−

π

2

,

π

2

]\{0}.

cot

−1

is neither odd nor even; it has domain R and range(0, π).

This is what the graphs look like:

PSfrag

replacements

(

a, b)

[

a, b]

(

a, b]

[

a, b)

(

a, ∞)

[

a, ∞)

(

−∞, b)

(

−∞, b]

(

−∞, ∞)

{

x : a < x < b}

{

x : a ≤ x ≤ b}

{

x : a < x ≤ b}

{

x : a ≤ x < b}

{

x : x ≥ a}

{

x : x > a}

{

x : x ≤ b}

{

x : x < b}

R

a

b

shado

w

0

1

4

−

2

3

−

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

mirror

(y = x)

f

−

1

(x) =

3

√

x

y = h

(x)

y = h

−

1

(x)

y =

(x − 1)

2

−

1

x

Same

height

−

x

Same

length,

opp

osite signs

y = −

2x

−

2

1

y =

1

2

x − 1

2

−

1

y =

2

x

y =

10

x

y =

2

−x

y =

log

2

(x)

4

3

units

mirror

(x-axis)

y = |

x|

y = |

log

2

(x)|

θ radians

θ units

30

◦

=

π

6

45

◦

=

π

4

60

◦

=

π

3

120

◦

=

2

π

3

135

◦

=

3

π

4

150

◦

=

5

π

6

90

◦

=

π

2

180

◦

= π

210

◦

=

7

π

6

225

◦

=

5

π

4

240

◦

=

4

π

3

270

◦

=

3

π

2

300

◦

=

5

π

3

315

◦

=

7

π

4

330

◦

=

11

π

6

0

◦

=

0 radians

θ

hypotenuse

opp

osite

adjacen

t

0

(≡ 2π)

π

2

π

3

π

2

I

I

I

I

II

IV

θ

(

x, y)

x

y

r

7

π

6

reference

angle

reference

angle =

π

6

sin

+

sin −

cos

+

cos −

tan

+

tan −

A

S

T

C

7

π

4

9

π

13

5

π

6

(this

angle is

5π

6

clo

ckwise)

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

y =

cos(x)

−

π

2

π

2

y =

tan(x), −

π

2

<

x <

π

2

0

−

π

2

π

2

y =

tan(x)

−

2π

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

y =

sec(x)

y =

csc(x)

y =

cot(x)

y = f (

x)

−

1

1

2

y = g(

x)

3

y = h

(x)

4

5

−

2

f(

x) =

1

x

g(

x) =

1

x

2

etc.

0

1

π

1

2

π

1

3

π

1

4

π

1

5

π

1

6

π

1

7

π

g(

x) = sin

1

x

1

0

−

1

L

10

100

200

y =

π

2

y = −

π

2

y =

tan

−1

(x)

π

2

π

y =

sin(

x)

x

,

x > 3

0

1

−

1

a

L

f(

x) = x sin (1/x)

(0 <

x < 0.3)

h

(x) = x

g(

x) = −x

a

L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) DNE

M

}

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = M

lim

x

→a

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) DNE

y = f (

x)

a

y =

|

x|

x

1

−

1

y =

|

x + 2|

x +

2

1

−

1

−

2

1

2

3

4

a

a

b

y = x sin

1

x

y = x

y = −

x

a

b

c

d

C

a

b

c

d

−

1

0

1

2

3

time

y

t

u

(

t, f(t))

(

u, f(u))

time

y

t

u

y

x

(

x, f(x))

y = |

x|

(

z, f(z))

z

y = f (

x)

a

tangen

t at x = a

b

tangen

t at x = b

c

tangen

t at x = c

y = x

2

tangen

t

at x = −

1

u

v

uv

u +

∆u

v +

∆v

(

u + ∆u)(v + ∆v)

∆

u

∆

v

u

∆v

v∆

u

∆

u∆v

y = f (

x)

1

2

−

2

y = |

x

2

− 4|

y = x

2

− 4

y = −

2x + 5

y = g(

x)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

y = f (

x)

3

−

3

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

easy

hard

flat

y = f

0

(

x)

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

1

−

1

y =

sin(x)

y = x

x

A

B

O

1

C

D

sin(

x)

tan(

x)

y =

sin

(x)

x

π

2

π

1

−

1

x =

0

a =

0

x

> 0

a

> 0

x

< 0

a

< 0

rest

position

+

−

y = x

2

sin

1

x

N

A

B

H

a

b

c

O

H

A

B

C

D

h

r

R

θ

1000

2000

α

β

p

h

y = g(x) = log

b

(x)

y = f(x) = b

x

y = e

x

5

10

1

2

3

4

0

−1

−2

−3

−4

y = ln(x)

y = cosh(x)

y = sinh(x)

y = tanh(x)

y = sech(x)

y = csch(x)

y = coth(x)

1

−1

y = f (x)

original function

inverse function

slope = 0 at (x, y)

slope is infinite at (y, x)

−108

2

5

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−1

−2

−3

−4

−5

−6

−3π

−

5π

2

−2π

−

3π

2

−π

−

π

2

3π

3π

5π

2

2π

3π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(x)

1

0

−1

−3π

−

5π

2

−2π

−

3π

2

−π

−

π

2

3π

5π

2

2π

2π

3π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(x)

y = sin(x), −

π

2

≤ x ≤

π

2

−2

−1

00

2

π

2

−

π

2

y = sin

−1

(x)

y = cos(x)

π

π

2

π

2

y = cos

−1

(x)

−

π

2

−

π

2

1

x

α

β

y = tan(x)

y = tan(x)

11

y = tan

−1

(x)

y = sec(x)

y = sec

−1

(x)

y = csc

−1

(x)

y = cot

−1

(x)

Both functions have horizontal asymptotes: y = csc

−1

(x) has a two-sided

horizontal asymptote at y = 0, and y = cot

−1

(x) has a left-hand horizontal

asymptote at y = π and a right-hand one at y = 0. We can summarize the

limits as follows:

218 • Inverse Functions and Inverse Trig Functions

lim

x→∞

csc

−1

(x) = 0 and lim

x→−∞

csc

−1

(x) = 0

lim

x→∞

cot

−1

(x) = 0 and lim

x→−∞

cot

−1

(x) = π.

Of course, if you know the above graphs, you can reconstruct the limits with-

out having to remember them. Notice that the graphs of y = csc

−1

(x) and

y = sec

−1

(x) from above are very similar; in fact, you can get one from the

other by flipping about the line y = π/4. This is exactly the same relation as

the one that y = sin

−1

(x) and y = cos

−1

(x) have with each other. So it’s not

surprising that the derivative of csc

−1

(x) is just the negative of the derivative

of sec

−1

(x):

d

dx

csc

−1

(x) = −

1

|x|

√

x

2

− 1

for x > 1 or x < −1.

The same thing happens with cot

−1

(x) and tan

−1

(x), so that

d

dx

cot

−1

(x) = −

1

1 + x

2

for all real x.

10.2.6 Computing inverse trig functions

We’ve completed a pretty thorough survey of the inverse trig functions. Since

you have a few more derivative rules, it’s a great idea to practice differentiating

functions involving inverse trig functions. Meanwhile, let’s not neglect some

basic computations involving inverse trig functions which don’t involve any

calculus. For one thing, you should try to make sure that you can compute

quantities like sin

−1

(1/2), cos

−1

(1), and tan

−1

(1) without stretching your

brain. For example, to find sin

−1

(1/2), remember that you’re looking for an

angle in [−π/2, π/2] whose sine is 1/2. Of course—it’s π/6. Similarly, it should

be almost second nature to write down cos

−1

(1) = 0 and tan

−1

(1) = π/4. All

the common values are in the table near the beginning of Chapter 2.

Now, here’s a more interesting question: how would you simplify

PSfrag

replacements

(

a, b)

[

a, b]

(

a, b]

[

a, b)

(

a, ∞)

[

a, ∞)

(

−∞, b)

(

−∞, b]

(

−∞, ∞)

{

x : a < x < b}

{

x : a ≤ x ≤ b}

{

x : a < x ≤ b}

{

x : a ≤ x < b}

{

x : x ≥ a}

{

x : x > a}

{

x : x ≤ b}

{

x : x < b}

R

a

b

shado

w

0

1

4

−

2

3

−

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

mirror

(y = x)

f

−

1

(x) =

3

√

x

y = h

(x)

y = h

−

1

(x)

y =

(x − 1)

2

−

1

x

Same

height

−

x

Same

length,

opp

osite signs

y = −

2x

−

2

1

y =

1

2

x − 1

2

−

1

y =

2

x

y =

10

x

y =

2

−x

y =

log

2

(x)

4

3

units

mirror

(x-axis)

y = |

x|

y = |

log

2

(x)|

θ radians

θ units

30

◦

=

π

6

45

◦

=

π

4

60

◦

=

π

3

120

◦

=

2

π

3

135

◦

=

3

π

4

150

◦

=

5

π

6

90

◦

=

π

2

180

◦

= π

210

◦

=

7

π

6

225

◦

=

5

π

4

240

◦

=

4

π

3

270

◦

=

3

π

2

300

◦

=

5

π

3

315

◦

=

7

π

4

330

◦

=

11

π

6

0

◦

=

0 radians

θ

hypotenuse

opp

osite

adjacen

t

0

(≡ 2π)

π

2

π

3

π

2

I

I

I

I

II

IV

θ

(

x, y)

x

y

r

7

π

6

reference

angle

reference

angle =

π

6

sin

+

sin −

cos

+

cos −

tan

+

tan −

A

S

T

C

7

π

4

9

π

13

5

π

6

(this

angle is

5π

6

clo

ckwise)

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

y =

cos(x)

−

π

2

π

2

y =

tan(x), −

π

2

<

x <

π

2

0

−

π

2

π

2

y =

tan(x)

−

2π

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

y =

sec(x)

y =

csc(x)

y =

cot(x)

y = f(

x)

−

1

1

2

y = g(

x)

3

y = h

(x)

4

5

−

2

f(

x) =

1

x

g(

x) =

1

x

2

etc.

0

1

π

1

2

π

1

3

π

1

4

π

1

5

π

1

6

π

1

7

π

g(

x) = sin

1

x

1

0

−

1

L

10

100

200

y =

π

2

y = −

π

2

y =

tan

−1

(x)

π

2

π

y =

sin(

x)

x

,

x > 3

0

1

−

1

a

L

f(

x) = x sin (1/x)

(0 <

x < 0.3)

h

(x) = x

g(

x) = −x

a

L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) DNE

M

}

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = M

lim

x

→a

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) DNE

y = f (

x)

a

y =

|

x|

x

1

−

1

y =

|

x + 2|

x +

2

1

−

1

−

2

1

2

3

4

a

a

b

y = x sin

1

x

y = x

y = −

x

a

b

c

d

C

a

b

c

d

−

1

0

1

2

3

time

y

t

u

(

t, f(t))

(

u, f(u))

time

y

t

u

y

x

(

x, f(x))

y = |

x|

(

z, f(z))

z

y = f(

x)

a

tangen

t at x = a

b

tangen

t at x = b

c

tangen

t at x = c

y = x

2

tangen

t

at x = −

1

u

v

uv

u +

∆u

v +

∆v

(

u + ∆u)(v + ∆v)

∆

u

∆

v

u

∆v

v∆

u

∆

u∆v

y = f(

x)

1

2

−

2

y = |

x

2

− 4|

y = x

2

− 4

y = −

2x + 5

y = g(

x)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

y = f (

x)

3

−

3

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

easy

hard

flat

y = f

0

(

x)

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

1

−

1

y =

sin(x)

y = x

x

A

B

O

1

C

D

sin(

x)

tan(

x)

y =

sin(

x)

x

π

2

π

1

−

1

x =

0

a =

0

x

> 0

a

> 0

x

< 0

a

< 0

rest

position

+

−

y = x

2

sin

1

x

N

A

B

H

a

b

c

O

H

A

B

C

D

h

r

R

θ

1000

2000

α

β

p

h

y = g(x) = log

b

(x)

y = f(x) = b

x

y = e

x

5

10

1

2

3

4

0

−1

−2

−3

−4

y = ln(x)

y = cosh(x)

y = sinh(x)

y = tanh(x)

y = sech(x)

y = csch(x)

y = coth(x)

1

−1

y = f(x)

original function

inverse function

slope = 0 at (x, y)

slope is infinite at (y, x)

−108

2

5

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−1

−2

−3

−4

−5

−6

−3π

−

5π

2

−2π

−

3π

2

−π

−

π

2

3π

3π

5π

2

2π

3π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(x)

1

0

−1

−3π

−

5π

2

−2π

−

3π

2

−π

−

π

2

3π

5π

2

2π

2π

3π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(x)

y = sin(x), −

π

2

≤ x ≤

π

2

−2

−1

0

2

π

2

−

π

2

y = sin

−1

(x)

y = cos(x)

π

π

2

y = cos

−1

(x)

−

π

2

1

x

α

β

y = tan(x)

y = tan(x)

1

y = tan

−1

(x)

y = sec(x)

y = sec

−1

(x)

y = csc

−1

(x)

y = cot

−1

(x)

sin

−1

sin

13π

10

?

The knee-jerk reaction is to cancel out the inverse sine and the sine, leaving

only 13π/10. This can’t be correct, though—the range of inverse sine is

[−π/2, π/2], as we saw in Section 10.2.1 above. What we really need to do

is find an angle in that range which has the same sine as 13π/10. Well, note

that 13π/10 is in the third quadrant, since it’s greater than π but less than

3π/2, so its sine is negative. Furthermore, the reference angle is 3π/10. The

possible angles in the range [π/2, π/2] with the same reference angle are 3π/10

and −3π/10. The first one has a positive sine, while the second has a negative

sine. We need a negative sine, so we’ve proved that

sin

−1

sin

13π

10

= −

3π

10

.

Section 10.2.6: Computing inverse trig functions • 219

Now, how about finding

PSfrag replacements

(

a, b)

[

a, b]

(

a, b]

[

a, b)

(

a, ∞)

[

a, ∞)

(

−∞, b)

(

−∞, b]

(

−∞, ∞)

{

x : a < x < b}

{

x : a ≤ x ≤ b}

{

x : a < x ≤ b}

{

x : a ≤ x < b}

{

x : x ≥ a}

{

x : x > a}

{

x : x ≤ b}

{

x : x < b}

R

a

b

shadow

0

1

4

−

2

3

−

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

mirror (

y = x)

f

−

1

(x) =

3

√

x

y = h

(x)

y = h

−

1

(x)

y = (

x − 1)

2

−

1

x

Same height

−

x

Same length,

opposite signs

y = −

2x

−

2

1

y =

1

2

x − 1

2

−

1

y = 2

x

y = 10

x

y = 2

−

x

y = log

2

(

x)

4

3 units

mirror (

x-axis)

y = |

x|

y = |

log

2

(x)|

θ radians

θ units

30

◦

=

π

6

45

◦

=

π

4

60

◦

=

π

3

120

◦

=

2

π

3

135

◦

=

3

π

4

150

◦

=

5

π

6

90

◦

=

π

2

180

◦

= π

210

◦

=

7

π

6

225

◦

=

5

π

4

240

◦

=

4

π

3

270

◦

=

3

π

2

300

◦

=

5

π

3

315

◦

=

7

π

4

330

◦

=

11

π

6

0

◦

= 0 radians

θ

hypotenuse

opposite

adjacent

0 (

≡ 2π)

π

2

π

3

π

2

I

II

III

IV

θ

(

x, y)

x

y

r

7

π

6

reference angle

reference angle =

π

6

sin +

sin −

cos +

cos −

tan +

tan −

A

S

T

C

7

π

4

9

π

13

5

π

6

(this angle is

5

π

6

clockwise)

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(

x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(

x)

y = cos(

x)

−

π

2

π

2

y = tan(

x), −

π

2

< x <

π

2

0

−

π

2

π

2

y = tan(

x)

−

2π

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

y = sec(

x)

y = csc(

x)

y = cot(

x)

y = f(

x)

−

1

1

2

y = g(

x)

3

y = h

(x)

4

5

−

2

f(

x) =

1

x

g(

x) =

1

x

2

etc.

0

1

π

1

2

π

1

3

π

1

4

π

1

5

π

1

6

π

1

7

π

g(

x) = sin

1

x

1

0

−

1

L

10

100

200

y =

π

2

y = −

π

2

y = tan

−

1

(x)

π

2

π

y =

sin(

x)

x

, x > 3

0

1

−

1

a

L

f(

x) = x sin (1/x)

(0 < x < 0

.3)

h

(x) = x

g(

x) = −x

a

L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) DNE

M

}

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = M

lim

x

→a

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) DNE

y = f (

x)

a

y =

|

x|

x

1

−

1

y =

|

x + 2|

x + 2

1

−

1

−

2

1

2

3

4

a

a

b

y = x sin

1

x

y = x

y = −

x

a

b

c

d

C

a

b

c

d

−

1

0

1

2

3

time

y

t

u

(

t, f(t))

(

u, f(u))

time

y

t

u

y

x

(

x, f(x))

y = |

x|

(

z, f(z))

z

y = f(

x)

a

tangent at x = a

b

tangent at x = b

c

tangent at x = c

y = x

2

tangent

at x = −

1

u

v

uv

u + ∆

u

v + ∆

v

(

u + ∆u)(v + ∆v)

∆

u

∆

v

u

∆v

v∆

u

∆

u∆v

y = f(

x)

1

2

−

2

y = |

x

2

− 4|

y = x

2

− 4

y = −

2x + 5

y = g(

x)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

y = f (

x)

3

−

3

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

easy

hard

flat

y = f

0

(

x)

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

1

−

1

y = sin(

x)

y = x

x

A

B

O

1

C

D

sin(

x)

tan(

x)

y =

sin(

x)

x

π

2

π

1

−

1

x = 0

a = 0

x > 0

a > 0

x < 0

a < 0

rest position

+

−

y = x

2

sin

1

x

N

A

B

H

a

b

c

O

H

A

B

C

D

h

r

R

θ

1000

2000

α

β

p

h

y = g(

x) = log

b

(x)

y = f(

x) = b

x

y = e

x

5

10

1

2

3

4

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

y = ln(

x)

y = cosh(

x)

y = sinh(

x)

y = tanh(

x)

y = sech(

x)

y = csch(

x)

y = coth(

x)

1

−

1

y = f(

x)

original function

inverse function

slope = 0 at (

x, y)

slope is infinite at (

y, x)

−

108

2

5

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−1

−2

−3

−4

−5

−6

−3π

−

5π

2

−2π

−

3π

2

−π

−

π

2

3π

3π

5π

2

2π

3π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(x)

1

0

−1

−3π

−

5π

2

−2π

−

3π

2

−π

−

π

2

3π

5π

2

2π

2π

3π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(x)

y = sin(x), −

π

2

≤ x ≤

π

2

−2

−1

0

2

π

2

−

π

2

y = sin

−1

(x)

y = cos(x)

π

π

2

y = cos

−1

(x)

−

π

2

1

x

α

β

y = tan(x)

y = tan(x)

1

y = tan

−1

(x)

y = sec(x)

y = sec

−1

(x)

y = csc

−1

(x)

y = cot

−1

(x)

cos

−1

cos

13π

10

?

The previous answer −3π/10 can’t be correct here, since the range of inverse

cosine is [0, π]. Man, why does this stuff have to be so messy? Nothing I

can do about it, unfortunately . . . so let’s deal with it like this: once again,

13π/10 is in the third quadrant, so its cosine is negative. The reference angle

is 3π/10; the only angles in [0, π] with the same reference angle are 3π/10 and

7π/10. The cosines of these two angles are positive and negative, respectively;

since we want a negative cosine, we must have

cos

−1

cos

13π

10

=

7π

10

.

I now leave it to you to show that

tan

−1

tan

13π

10

=

3π

10

.

Just remember that tan is positive in the third quadrant! In any case, those

are all difficult examples, so I wouldn’t blame you if you also thought that

finding

sin

sin

−1

−

1

5

would be hard as well. Luckily, it’s not: the answer is just −1/5. In general,

sin(sin

−1

(x)) = x, provided that x is in the domain [−1, 1] of inverse sine.

(Otherwise, sin(sin

−1

(x)) doesn’t even make sense!) The trouble comes when

you try to write sin

−1

(sin(x)) = x. This just isn’t true, as the above example

where x = 13π/10 shows. Of course, the same observations apply to all the

other inverse trig functions. (See also the discussion at the end of Section 1.2

in Chapter 1.)

Two more examples: consider how you would find

PSfrag replacements

(

a, b)

[

a, b]

(

a, b]

[

a, b)

(

a, ∞)

[

a, ∞)

(

−∞, b)

(

−∞, b]

(

−∞, ∞)

{

x : a < x < b}

{

x : a ≤ x ≤ b}

{

x : a < x ≤ b}

{

x : a ≤ x < b}

{

x : x ≥ a}

{

x : x > a}

{

x : x ≤ b}

{

x : x < b}

R

a

b

shadow

0

1

4

−

2

3

−

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

mirror (

y = x)

f

−

1

(x) =

3

√

x

y = h

(x)

y = h

−

1

(x)

y = (

x − 1)

2

−

1

x

Same height

−

x

Same length,

opposite signs

y = −

2x

−

2

1

y =

1

2

x − 1

2

−

1

y = 2

x

y = 10

x

y = 2

−

x

y = log

2

(

x)

4

3 units

mirror (

x-axis)

y = |

x|

y = |

log

2

(x)|

θ radians

θ units

30

◦

=

π

6

45

◦

=

π

4

60

◦

=

π

3

120

◦

=

2

π

3

135

◦

=

3

π

4

150

◦

=

5

π

6

90

◦

=

π

2

180

◦

= π

210

◦

=

7

π

6

225

◦

=

5

π

4

240

◦

=

4

π

3

270

◦

=

3

π

2

300

◦

=

5

π

3

315

◦

=

7

π

4

330

◦

=

11

π

6

0

◦

= 0 radians

θ

hypotenuse

opposite

adjacent

0 (

≡ 2π)

π

2

π

3

π

2

I

II

III

IV

θ

(

x, y)

x

y

r

7

π

6

reference angle

reference angle =

π

6

sin +

sin −

cos +

cos −

tan +

tan −

A

S

T

C

7

π

4

9

π

13

5

π

6

(this angle is

5

π

6

clockwise)

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(

x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(

x)

y = cos(

x)

−

π

2

π

2

y = tan(

x), −

π

2

< x <

π

2

0

−

π

2

π

2

y = tan(

x)

−

2π

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

y = sec(

x)

y = csc(

x)

y = cot(

x)

y = f(

x)

−

1

1

2

y = g(

x)

3

y = h

(x)

4

5

−

2

f(

x) =

1

x

g(

x) =

1

x

2

etc.

0

1

π

1

2

π

1

3

π

1

4

π

1

5

π

1

6

π

1

7

π

g(

x) = sin

1

x

1

0

−

1

L

10

100

200

y =

π

2

y = −

π

2

y = tan

−

1

(x)

π

2

π

y =

sin(

x)

x

, x > 3

0

1

−

1

a

L

f(

x) = x sin (1/x)

(0 < x < 0

.3)

h

(x) = x

g(

x) = −x

a

L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) DNE

M

}

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = M

lim

x

→a

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) DNE

y = f (

x)

a

y =

|

x|

x

1

−

1

y =

|

x + 2|

x + 2

1

−

1

−

2

1

2

3

4

a

a

b

y = x sin

1

x

y = x

y = −

x

a

b

c

d

C

a

b

c

d

−

1

0

1

2

3

time

y

t

u

(

t, f(t))

(

u, f(u))

time

y

t

u

y

x

(

x, f(x))

y = |

x|

(

z, f(z))

z

y = f(

x)

a

tangent at x = a

b

tangent at x = b

c

tangent at x = c

y = x

2

tangent

at x = −

1

u

v

uv

u + ∆

u

v + ∆

v

(

u + ∆u)(v + ∆v)

∆

u

∆

v

u

∆v

v∆

u

∆

u∆v

y = f(

x)

1

2

−

2

y = |

x

2

− 4|

y = x

2

− 4

y = −

2x + 5

y = g(

x)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

y = f (

x)

3

−

3

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

easy

hard

flat

y = f

0

(

x)

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

1

−

1

y = sin(

x)

y = x

x

A

B

O

1

C

D

sin(

x)

tan(

x)

y =

sin(

x)

x

π

2

π

1

−

1

x = 0

a = 0

x > 0

a > 0

x < 0

a < 0

rest position

+

−

y = x

2

sin

1

x

N

A

B

H

a

b

c

O

H

A

B

C

D

h

r

R

θ

1000

2000

α

β

p

h

y = g(x) = log

b

(x)

y = f(x) = b

x

y = e

x

5

10

1

2

3

4

0

−1

−2

−3

−4

y = ln(x)

y = cosh(x)

y = sinh(x)

y = tanh(x)

y = sech(x)

y = csch(x)

y = coth(x)

1

−1

y = f(x)

original function

inverse function

slope = 0 at (x, y)

slope is infinite at (y, x)

−108

2

5

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−1

−2

−3

−4

−5

−6

−3π

−

5π

2

−2π

−

3π

2

−π

−

π

2

3π

3π

5π

2

2π

3π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(x)

1

0

−1

−3π

−

5π

2

−2π

−

3π

2

−π

−

π

2

3π

5π

2

2π

2π

3π

2

π

π

2

y = sin(x)

y = sin(x), −

π

2

≤ x ≤

π

2

−2

−1

0

2

π

2

−

π

2

y = sin

−1

(x)

y = cos(x)

π

π

2

y = cos

−1

(x)

−

π

2

1

x

α

β

y = tan(x)

y = tan(x)

1

y = tan

−1

(x)

y = sec(x)

y = sec

−1

(x)

y = csc

−1

(x)

y = cot

−1

(x)

sin

cos

−1

√

15

4

!!

and sin

cos

−1

−

√

15

4

!!

.

The trick in both cases is to use the trig identity cos

2

(x) + sin

2

(x) = 1. For

the first problem, let

x = cos

−1

√

15

4

!

and note that we want to find sin(x). We actually know cos(x):

cos(x) = cos

cos

−1

√

15

4

!!

=

√

15

4

.

Remember, there’s no problem taking the cosine of an inverse cosine: it’s only

the other way around that poses a problem. Anyway, we know cos(x), so by

220 • Inverse Functions and Inverse Trig Functions

rearranging the identity cos

2

(x) + sin

2

(x) = 1, we must have

sin(x) = ±

p

1 − cos

2

(x) = ±

v

u

u

t

1 −

√

15

4

!

2

= ±

r

1

16

= ±

1

4

.

So the answer we want is either 1/4 or −1/4. Which one is it? Well, since

√

15/4 is positive, inverse cosine of it must lie in [0, π/2]. That is, x is in the

first quadrant, so its sine is positive. We’ve finally shown that

sin

cos

−1

√

15

4

!!

=

1

4

.

As for

sin

cos

−1

−

√

15

4

!!

,

you can repeat the above argument to show that

sin(x) = ±

p

1 − cos

2

(x) = ±

v

u

u

t

1 −

−

√

15

4

!

2

= ±

r

1

16

= ±

1

4

.

You might guess that the answer this time is −1/4, but that’s no good. You

see, −

√

15/4 is negative, so its inverse cosine must lie in the interval [π/2, π].

That is, x is in the second quadrant. The thing is, sine is positive in the

second quadrant as well! So sin(x) must be positive, and we’ve shown that

sin

cos

−1

−

√

15

4

!!

=

1

4

as well. In fact, we’ve noticed that sin(cos

−1

(A)) must always be nonnegative,

even if A is negative (note that A has to lie in [−1, 1], since that’s the domain

of inverse cosine). This is because cos

−1

(A) is in the interval [0, π], and sine

is nonnegative on that interval.

We’ll actually look at another method of finding things like sin(cos

−1

(A))

when we see how to do trig substitutions in Section 19.3 of Chapter 19. For

now, let’s take a well-deserved rest from inverse trig functions and take a quick

look at inverse hyperbolic functions.

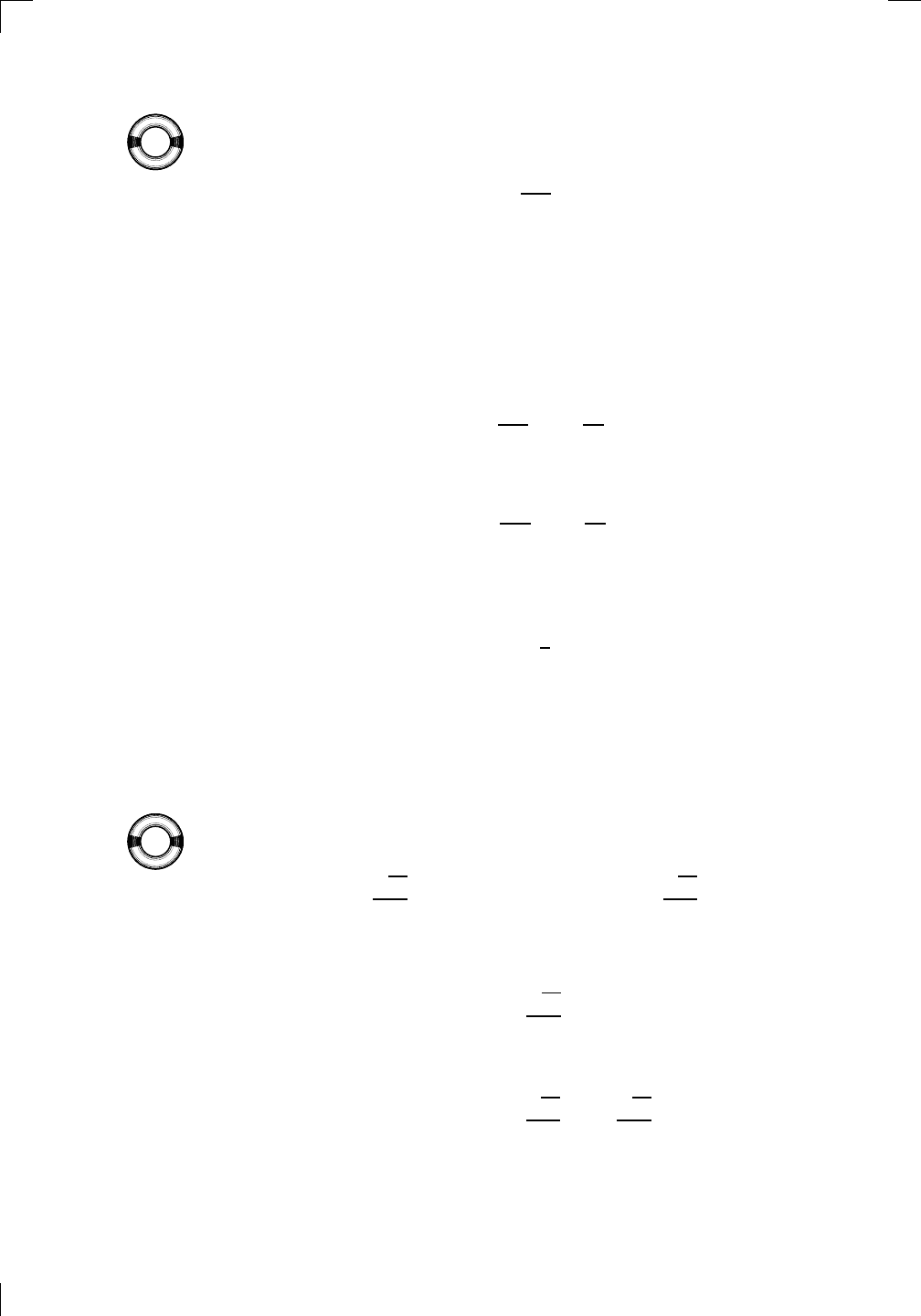

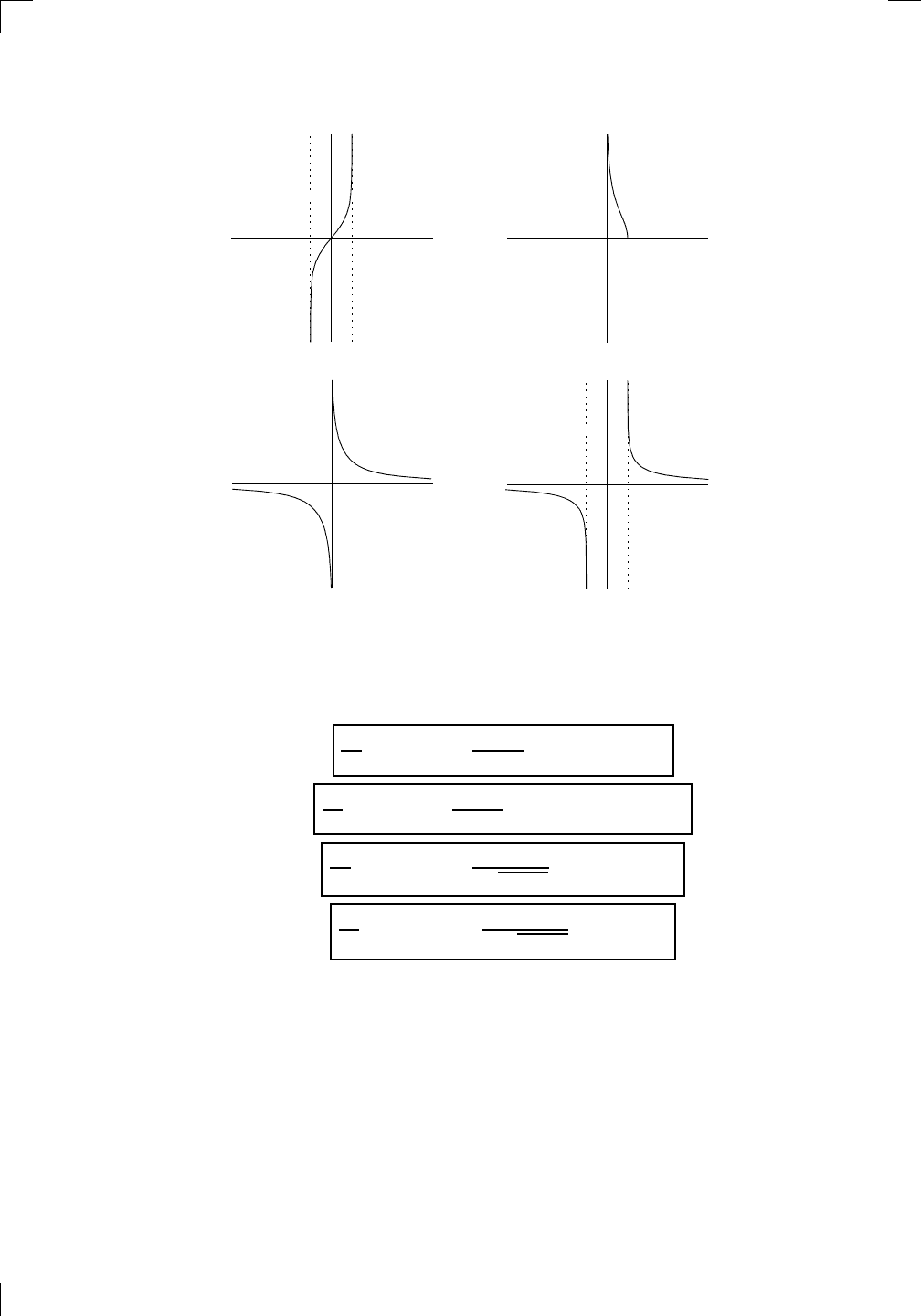

10.3 Inverse Hyperbolic Functions

The situation is a little different for hyperbolic functions, which we looked at

in Section 9.7 of the previous chapter. Look back now and remind yourself

what the graphs of these functions look like. In particular, you can see that

the graph of y = cosh(x) is sort of like the graph of y = x

2

, except shifted up

by 1 and shaped a little differently. If you want an inverse for this function,

you have to throw away the left half of the graph, just as you do when you

take the positive square root (and throw away the negative one). On the other

Section 10.3: Inverse Hyperbolic Functions • 221

hand, y = sinh(x) already satisfies the horizontal line test, so there’s nothing

that needs to be done. So we get two inverse functions with the following

properties:

cosh

−1

is neither odd nor even; it has domain [1, ∞) and range [0, ∞).

sinh

−1

is odd; its domain and range are all of R.

The graphs are obtained by reflecting the original graphs in the line y = x as

usual:

PSfrag

replacements

(

a, b)

[

a, b]

(

a, b]

[

a, b)

(

a, ∞)

[

a, ∞)

(

−∞, b)

(

−∞, b]

(

−∞, ∞)

{

x : a < x < b}

{

x : a ≤ x ≤ b}

{

x : a < x ≤ b}

{

x : a ≤ x < b}

{

x : x ≥ a}

{

x : x > a}

{

x : x ≤ b}

{

x : x < b}

R

a

b

shado

w

0

1

4

−

2

3

−

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

mirror

(y = x)

f

−

1

(x) =

3

√

x

y = h

(x)

y = h

−

1

(x)

y =

(x − 1)

2

−

1

x

Same

height

−

x

Same

length,

opp

osite signs

y = −

2x

−

2

1

y =

1

2

x − 1

2

−

1

y =

2

x

y =

10

x

y =

2

−x

y =

log

2

(x)

4

3

units

mirror

(x-axis)

y = |

x|

y = |

log

2

(x)|

θ radians

θ units

30

◦

=

π

6

45

◦

=

π

4

60

◦

=

π

3

120

◦

=

2

π

3

135

◦

=

3

π

4

150

◦

=

5

π

6

90

◦

=

π

2

180

◦

= π

210

◦

=

7

π

6

225

◦

=

5

π

4

240

◦

=

4

π

3

270

◦

=

3

π

2

300

◦

=

5

π

3

315

◦

=

7

π

4

330

◦

=

11

π

6

0

◦

=

0 radians

θ

hypotenuse

opp

osite

adjacen

t

0

(≡ 2π)

π

2

π

3

π

2

I

I

I

I

II

IV

θ

(

x, y)

x

y

r

7

π

6

reference

angle

reference

angle =

π

6

sin

+

sin −

cos

+

cos −

tan

+

tan −

A

S

T

C

7

π

4

9

π

13

5

π

6

(this

angle is

5π

6

clo

ckwise)

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

y =

cos(x)

−

π

2

π

2

y =

tan(x), −

π

2

<

x <

π

2

0

−

π

2

π

2

y =

tan(x)

−

2π

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

y =

sec(x)

y =

csc(x)

y =

cot(x)

y = f(

x)

−

1

1

2

y = g(

x)

3

y = h

(x)

4

5

−

2

f(

x) =

1

x

g(

x) =

1

x

2

etc.

0