Balian E.V., L?v?que C., Segers H., Martens K. (Eds.) Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Theowald, B., 1967. Familie Tipulidae (Diptera, Nematocera).

Larven und Puppen. Bestimmungsbu

¨

cher zur Bodenfauna

Europas 7: 1–100.

Theowald, B., 1973–1980. Tipulidae. Fliegen der Palaearktis-

chen Region 3(5) 1: 321–538.

Theowald, B., 1984. Taxonomie, Phylogenie und Biogeogra-

phie der Untergattung Tipula (Tipula) Linnaeus, 1758

(Insecta, Diptera, Tipulidae). Tijdschrift voor Entomolo-

gie 127: 33–78.

Wood, H. G., 1952. The crane-flies of the South-West Cape.

Annals of the South African Museum 39: 1–327.

Wood, D. M., & A. Borkent, 1989. Phylogeny and classifica-

tion of the Nematocera. In McAlpine, J. F. & D. M. Wood

(eds), Manual of Nearctic Diptera, Vol. 3. Research

Branch, Agriculture Canada, Monograph 32: 1333–1370.

Young, C. W., 2004. Insecta: Diptera, Tipulidae. In Yule, C.

M. & Y. H. Sen (eds), Freshwater Invertebrates of the

Malaysian Region: 775–785.

Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:457–467 467

123

FRESHWATER ANIMAL DIVERSITY ASSESSMENT

Global diversity of black flies (Diptera: Simuliidae)

in freshwater

Douglas C. Currie Æ Peter H. Adler

Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2007

Abstract Black flies are a worldwide family of

nematocerous Diptera whose immature stages are

confined to running waters. They are key organisms in

both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, but are perhaps

best known for the bloodsucking habits of adult females.

Attacks by black flies are responsible for reduced

tourism, deaths in wild and domestic birds and

mammals, and transmission of parasitic diseases to

hosts, including humans. About 2,000 nominal species

are currently recognized; however, certain geographical

regions remain inadequately surveyed. Furthermore,

studies of the giant polytene chromosomes of larvae

reveal that many morphologically recognized species

actually consist of two or more structurally indistin-

guishable (yet reproductively isolated) sibling species.

Calculations derived from the best-known regional

fauna—the Nearctic Region—reveal that the actual

number of World black fly species exceeds 3,000.

Keywords Simuliidae Lotic Filter-feeders

Bloodsuckers Sibling species Bioindicators

Introduction

Black flies (Simuliidae) represent a relatively small

and structurally homogeneous family of nematocer-

ous Diptera. They are most closely related to the

Ceratopogonidae, Chironomidae, and Thaumaleidae,

which collectively form the culicomorphan super-

family Chironomoidea. The 2000 nominal species of

black flies are worldwide in distribution, occurring on

all continents except Antarctica. They also populate

most major archipelagos except Hawaii, the Falkland

Islands, and isolated desert islands.

As with other holometabolous insects, black flies

pass through four stages to complete their develop-

ment: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. The first three

stages are confined to running waters which, depend-

ing on speci es, can range in size from tiny headwaters

to large rivers. Eggs are deposited on a variety of

submerged or emergent substrata, or are simply

dropped into the water where they settle into the

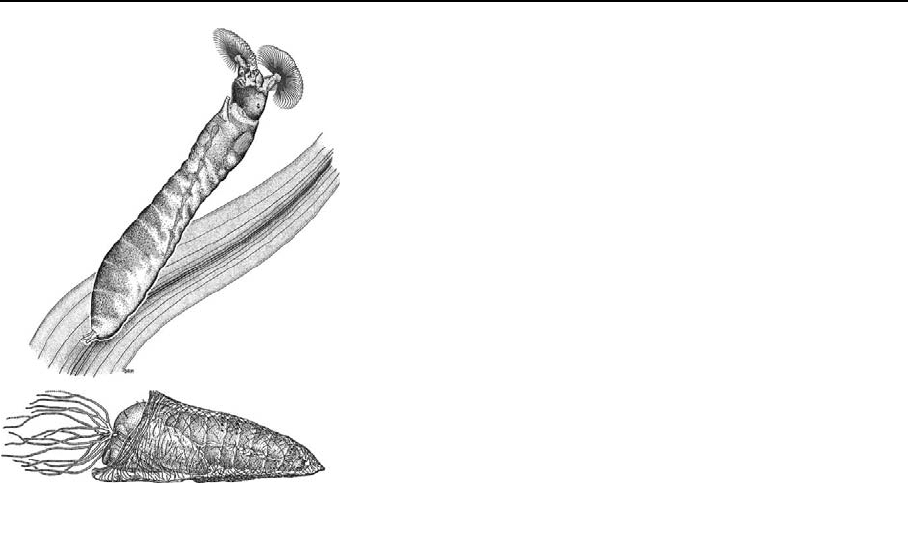

sediments. Larvae (Fig. 1, top) are sausage-shaped

organisms with a well-sclerotized external head

capsule that typically bears a pair of labral fans.

Guest editors: E.V. Balian, C. Le

´

ve

ˆ

que, H. Segers &

K. Martens

Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment

Electronic supplementary material The online version of

this article (doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9114-1) contains supple-

mentary material, which is available to authorized users.

D. C. Currie (&)

Department of Natural History, Royal Ontario Museum,

Toronto, ON, Canada

e-mail: dcurrie@zoo.utoronto.ca

P. H. Adler

Department of Entomology, Clemson University,

Clemson, SC, USA

e-mail: padler@clemson.edu

123

Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:469–475

DOI 10.1007/s10750-007-9114-1

The thorax bears a single-ventral prothoracic proleg,

and the last abdominal segment terminates with a

posterior proleg that serves as an attachment organ.

Larvae typically pass through seven instars to reach

maturity. The fully mature larva (pharate pupa) spins

a variously shaped silken cocoon in which to pupate.

The pupa (Fig. 1, bottom) is remarkably uniform in

shape and reflects the shape of the future adult. A pair

of spiracular gills arises from the anterolateral

corners of the thorax and typically projects anteriorly

or anterodorsally. The gill consists of a number of

slender filaments, or in some species it is tubular,

club shaped, or spherical. The adults are small,

hunchbacked flies with cigar-shaped antennae . Their

wings are broad at the base with darkly sclerotized

anterior veins and weakly sclerotized posterior veins.

Both sexes require sugar s (nectar, honeydew) as a

source of energy for flight and other metabolic needs.

Females of most species require blood from homeo-

thermic hosts (mammals or birds) to develop their

eggs. During blood feeding, black flies can transmit

parasitic disease agents to their hosts. Some species

(ca. 2.4% of the world fauna) have mouthparts that

are feebly developed and unable to cut flesh (Cross-

key, 1990). These obligatorily autogenous species

develop their eggs in the absence of blood.

Black flies are key organisms in both aquatic and

terrestrial ecosystems , especially in the boreal biome

of the Nearctic and Palearctic Regions (Malmqvist

et al., 2004). Larvae occur in huge numb ers under

favorable conditions, attaining population densities

of up to a million individuals/m

2

. Under such

densely packed conditions, they are an important

source of food for many invertebrate (e.g., plecopt-

eran) and vertebrate predators (e.g., salmonids). The

filter-feeding habit of larvae plays a role in the

processing of organic matter in streams. Fine

particulate organic matter, and even dissolved

organic matter, is removed from the water column

and, as a conse quence of the larva’s low-digestion

efficiency, is egested as nutritious fecal pellets. The

pellets sink rapidly to the streambed where they

serve as food for members of the collector–gatherer

functional feeding guild of invertebrates. Were it not

for the black fly larva’s ability to assimilate such

fine particles, much of the organic matter entrained

in the water column would be transported down-

stream. The importance of fecal pellets in streams

was highlighted by a study for a single river in

Sweden that showed the average daily transport of

fecal pellets reached a staggering 429 tonnes (dry

mass) past an imaginary line across the river

(Malmqvist et al., 2001). This massive amount of

recycled organic matter provides crucial fodder for

invertebrates and microorganisms, and has the

potential to fertilize river valleys (Malmqvist et al.,

2004).

Species & generi c diversity

As one of the most prominent members of the benthic

community and the second most important group of

medically important insects, the family Simuliidae is

among the most completely known groups of fresh-

water arthropods. The Simuliidae, along with the

Culicidae in part, are unique among freshwater

organisms in that their taxonomy has been greatly

aided by band-by-band analyses of the giant polytene

chromosomes in the larval silk glands. These giant

chromosomes have routinely allowed the discovery

of morphologically indistinguishable species. Despite

these taxonomic promoters, we suspect that a signif-

icant proportion of the world’s simuliid fauna

remains undiscovered.

Fig. 1 Simuliidae Habitus: larva (top) (source: Currie, 1986),

pupa (bottom) (source: Peterson, 1981)

470 Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:469–475

123

Approximately 2000 nominal species of extant

black flies in 26 nominal genera are recognized as

valid through mid-2006 (Crosskey & Howard, 2004;

Adler & Crosskey, unpublished) (Tables 1, 2). We

base our estimates of the absolute number of

simuliids on mentations deri ved from one of the

best-known regional faunas—the Nearctic fauna

(Adler et al., 2004). Out of the 256 species of

Nearctic black flies, 186 have had some level of

chromosomal screening, albeit minimal in some

cases. As a result of these chromosomal studies, 60

species (32.2%) were added to the Nearctic fauna. If

we use 32.2% as a minimal estimate of hidden

biodiversity (i.e., sibling species), the Nearctic fauna

will increase by 23 species (i.e., 32.2% of the 70

chromosomally unscreened species), yielding a total

of 279 species. Each of the remaining major regional

faunas also would increase by 32.2% of the total

number of nominal species known from each region,

yielding species counts of 283 (Afrotropical), 258

(Australasian), 469 (Neotropical), 424 (Oriental), 73

(Pacific), and 924 (Palearctic).

The estimate derived for hidden biodiversity is

a minimum value. Although giant chromosomes

provide powerful prima facie evidence of reproduc-

tive isolation among species when two opposite and

fixed chromosomal sequences are present in sympa-

try, they cannot always be used to reveal good

species. Since Y-chromosome differences occur in

the heterozygous condition—male black flies are

typically XY—the giant chromosomes cannot always

provide a distinction between two possibilities:

separate speci es or a Y-chromosome polymorphism

within one species. Given the high frequency of cases

where different Y-chromosomes occur among puta-

tively single species, we expect that the numb er of

additional sibling species is considerable. Similarly,

giant chromosomes cannot always reveal homose-

quential sibling species, which are not only

morphologically indistinguishable, but also have the

same chromosomal banding sequences. These species

are real (e.g., Henderson, 1986), but too little

prospecting has been done to provide an estimate of

their numbers among the Simuliidae. We suspect that

the number of homosequential sibling species would

easily balance the number of potential synonyms, and

for purposes of predicting the absolute number of

species we here consider them to cancel one another.

Table 1 Numbers of simuliid species in each biogeographical region for the family, subfamilies, and tribes

PA NA AT NT OL AU PAC ANT World

*

Simuliidae 699 256 214 355 321 195 55 2 2000

Parasimuliinae 0 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 4

Simuliinae 699 252 214 355 321 195 55 2 1996

Prosimuliini 77 62 0 0 0 0 0 0 136

Simuliini 622 190 214 355 321 195 55 2 1860

PA: Palaearctic; NA: Nearctic; NT: Neotropical; AT: Afrotropical ; OL: Oriental; AU: Australasian; PAC: Pacific Oceanic Islands;

ANT: Antarctic

*

Grand totals reflect not only species endemic to a region but also shared species

Table 2 Numbers of simuliid genera in each biogeographical region for the family, subfamilies, and tribes

PA NA AT NT OL AU PAC ANT World

*

Simuliidae 12 13 2 10 1 2 1 1 26

Parasimuliinae 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

Simuliinae 12 12 2 10 1 2 1 1 25

Prosimuliini 6 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 6

Simuliini 6 8 2 10 1 2 1 1 20

PA: Palaearctic; NA: Nearctic; NT: Neotropical; AT: Afrotropical ; OL: Oriental; AU: Australasian; PAC: Pacific Oceanic Islands;

ANT: Antarctic

*

Grand totals reflect not only species endemic to a region but also shared species

Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:469–475 471

123

Estimating the number of morphologically distinct

species yet to be discovered is more problematic. In

areas such as western Europe and North America, the

number is probably quite low; only one new

morphologically distinct species has been found in

the Nearctic Region and none in western Europe in

the past four years. On the other hand, in poorly

explored hot spots, such as the Himalayas, Cambodia,

Peru, and the interior of Irian Jaya, the number is

likely to be large; for example, 71 morphologically

distinct species were found on five major Indonesian

islands in the past four years (Takaoka, 2003). We

suggest that a 5% increase in the number of

morphologically distinct species above the currently

recognized numb er of nominal species in the Nearctic

and Palearctic Regions is reasonable, yielding an

increase of 13 and 35 species, respectively. For the

Afrotropical, Australasian, Neotropical, Oriental, and

Pacific Regions, we estimate a 25% increase in

species numbers, yielding increas es of 54, 49, 89, 80,

and 14 species, respectively. Considering the number

of potentially undiscovered morphospecies and sib-

ling species, we suspect that the total number of black

flies in the world is more than 3000, with regi onal

contributions to this grand total as follows: 337

(Afrotropical), 2 (Antarctic), 307 (Australasian), 292

(Nearctic), 558 (Neotropical), 504 (Oriental), 87

(Pacific), and 959 (Palearctic).

Phylogeny and historical processes

The earliest definitive simuliid fossils date to late

Jurassic times (Kalugina, 1991; Currie and Grimaldi,

2000); however, the fossil record of related families

suggests that black flies must have originated con-

siderably earlier. The family Simuliidae, therefore,

likely had a Pangean, or effectively Pangean, origin.

There are no comprehensive phylogenies of the

world Simuliidae—at least, none that are reconstructed

in an explicitly phylogenetic framework. Adler et al.

(2004) provided a cladistic analysis of the genera and

subgenera of Holarctic black flies, and Moulton (2000)

provided an interpretation of suprageneric relation-

ships based on his analysis of molecular sequence data.

Both studies recognized a two-subfamily system

(Parasimuliinae and Simuliinae), of which the latter

was divided into two tribes (Prosimuliini and Simuli-

ini); this system is the one followed here. Members of

the subfamily Parasimuliinae exhibit a relict distribu-

tion, occurring only in the coastal mountains of western

North America. Within the subfamily Simuliinae,

members of the tribe Prosimuliini occur only in the

Nearctic and Palearctic Regions, whereas the most

plesiomorphic members of the tribe Simuliini occur in

the Afrotropical, Australasian, and Neotropical

Regions. These distributions suggest that the two

tribes originated in Laurasia and Gondwanaland,

respectively (Currie, 1988).

Present distribution and main areas of endemicity

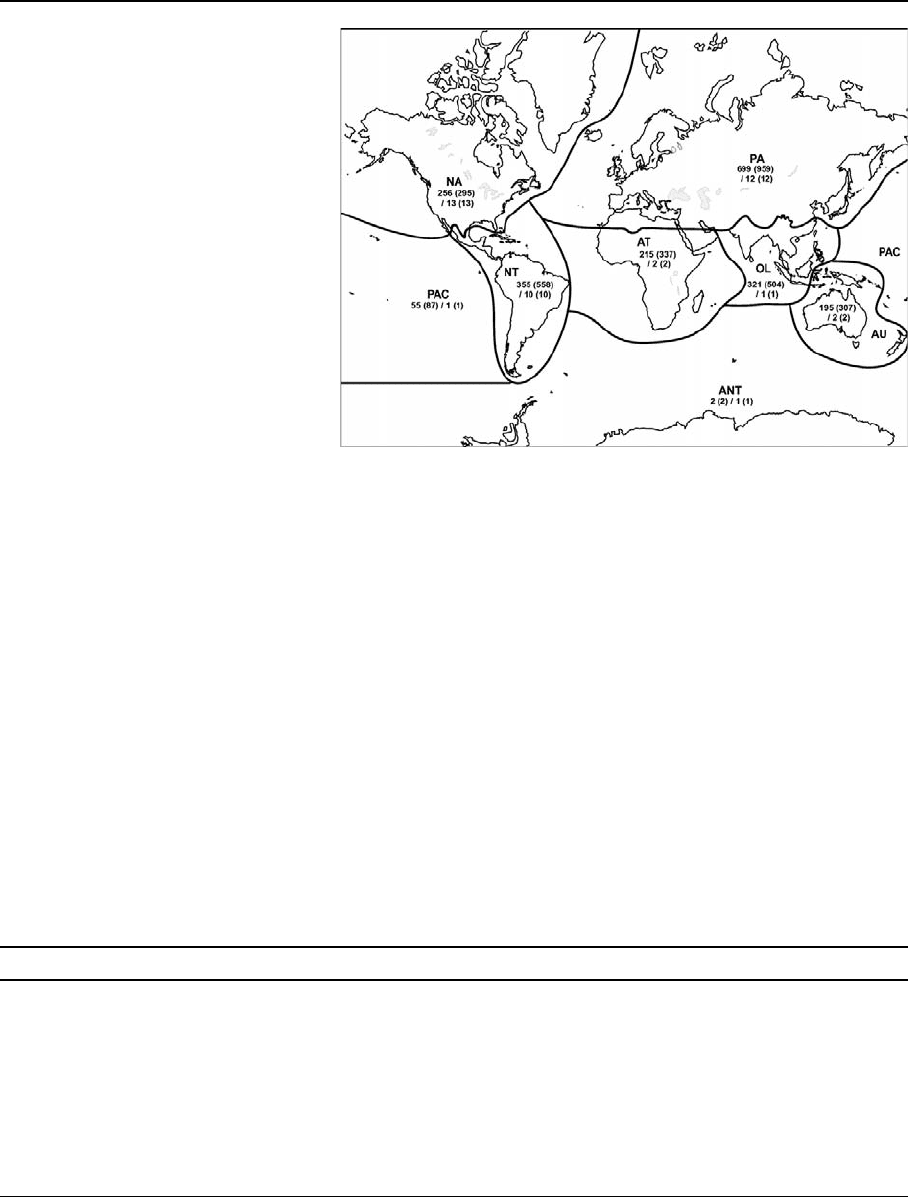

The Palearctic Region has by far the largest number

of described species (Fig. 2), although the dubious

taxonomic practices of earlier specialists suggest that

many synonyms probably exist among the names of

currently recognized species . Nonetheless, significant

parts of the Palearctic Region (e.g., Himalayas)

remain inadequately surveyed and the current pre-

diction of 959 species might not be unreasona ble. The

Nearctic Region—the most completely surveyed

faunal area—has far fewer than half that number of

predicted species. The Neotropical and Oriental

Regions have roughly equal numbers of species

(558 and 504 species, respectively), although the

latter region has not received the same intensity of

taxonomic scrutiny as the former.

South Asia is in particular need of study. Rela-

tively few taxonomic stud ies have been conducted in

the area, consisting mainly of isolated species

descriptions. The simuliid fauna of the Afrotropical

Region has received consi derable attention, but most

of this effort has been directed toward vectors (e.g.,

Simulium damnosum complex) of the causal agent of

human onchocerciasis. The Australasian Region has

not been intensively studied since the early 1970s

(e.g., Mackerras & Mackerras, 1952; Dumbleton,

1973). Indeed, the 71 species recently described from

Irian Jaya, Maluku, and Sulawesi (Takaoka, 2003)

represent more than 36% of all the morphospecies

currently recognized from Australasia . More inten-

sive surveys in Irian Jaya, Papua New Guinea, and

Western Australia will increase the number of species

for the region. The simuliid faunas of Antarctica

(Crozet Islands) and the Pacific Oceanic Islands have

been well surveyed (e.g., Craig et al., 2003; Craig &

Joy, 2000); yet, additional species continue to be

472 Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:469–475

123

discovered in the Pacific Region as new collections

are made.

The Nearctic and Oriental Regions have the fewest

endemic taxa among the major zoogeographic areas,

perhaps owing in part to their close association with

the Palearctic Region (Tables 1, 2). The Neotropical

Region has by far the largest number of endemic

genus-group taxa; however, a number of currently

recognized ‘valid ’ names (e.g., Kempfsimulium,

Pedrowygomyia) undoubtedly will fall into synon-

ymy, as phylogenetic relationships become b etter

understood. In contrast, several additional genus-

group taxa will have to be recogniz ed for species that

are currently assigned to the Australian ‘‘Paracne-

phia.’’ The Afrotropical Region, with its 11 unique

genus-group taxa, is second only to the Neotropical

Region in terms of endemicity. Antarctica (Crozet

Islands) and the Pacific Oceanic Islands have one and

two endemic genus-group taxa, respectively.

In terms of faunal similarities, the Nearctic and

Palearctic Regions share by far the greatest number

(18) of genus-group taxa (Table 3). The Nearctic and

Neotropical Regions share six genus-group taxa, as

do the Palearc tic and Oriental Regions. At the other

end of the spectrum, Antarctica (Crozet Islands), with

its one endemic genus (Crozetia), exhibits no clear

relationship with any other zoogeographical region

(Craig et al., 2003) (Table 3).

Human-related issues

The bloodsucking habits of female simuliids are

responsible for considerable deleterious effects on

Fig. 2 Known and

Estimated (numbers in

parentheses) diversity of

black flies in each

zoogeographic region

(Species / Genera). PA,

Palaearctic; NA, Nearctic;

NT, Neotropical; AT,

Afrotropical; OL, Oriental;

AU, Australasian; PAC,

Pacific Oceanic Islands;

ANT, Antarctic

Table 3 Genus-group taxa of Simuliidae shared among zoogeographic regions

PA NA NT AT OL AU PAC ANT

PA –

NA 18 –

NT 2 6 –

AT 2 2 0 –

OL 6 4 1 2 –

AU32024–

PAC 1 0 0 0 1 2 –

ANT 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 –

PA = Palear ctic, NA = Nearctic, NT = Neotropical, AT = Afrotropical, OL = Oriental, AU = Australasian, PAC = Pacific Oceanic

Islands, ANT = Antarctic

Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:469–475 473

123

humans and their economic welfare (Crosskey,

1990). Reduced tourism, deaths of domesticated

birds and mammals, and transmission of parasitic

disease organisms are but a few of the myriad

medical and socioeconomic impacts associated with

black flies. Human onchocerciasis (river blindness) is

the most pressing health-related issue, with up to 18

million people infected in parts of Africa and South

and Central America. The causative organism,

Onchocerca volvulus, is transmitted exclusively by

black flies —predominantly members of the Simulium

damnosum complex in Africa and members of the

Simulium subgenera Aspathia and Psilopelmia in

South and Central Amer ica (Crosskey, 1990). In

addition to being the sole vectors of the disease agent

of river blindness, black flies are pests of humans due

to their swarming and bloodsucking behavior. How-

ever, no species of black fly feeds exclusively on

humans, and relatively few species include humans

among their hosts. Massive outbreaks of anthropo-

philic species, nonetheless, can have a great impact

on tourism and other forms of human activity.

Black flies are also responsible for transmitting

parasitic disease organisms, such as filarial worms,

protozoans, and arboviruses to a wide variety of

domesticated animals (Adler, 2005). Massive attacks

by livestock pests such as Cnephia pecuarum,

Simulium colombaschense, Simulium luggeri, and

Simulium vampirum have caused mortality in cattle,

horses, mules, pigs, and sheep. Deaths in such

instances are typically attributed to toxic shock

(simuliotoxicosis) from the salivary injections of

many bites. Sublethal attacks can have an economic

impact through unrealized weight gains, reduced milk

production, malnutrition, impotence, and stress-

related phenomena (Adler et al., 2004). The effects

of black flies on wild birds and mammals are

inadequately studied, but are likely to be as great as

those reported for domesticated animals.

Black flies have a negative reputation because of

the bloodsucking habit of the females. On a more

positive note, the adults provide food for predators,

such as birds and odonates, and promote conserva-

tion by deterring people from inhabiting or

developing wilderness areas. The immature stages

not only play a dominant role in lotic communities

by processing organic matter, but also are sensitive

to anthropogenic inputs and are thus excellent

barometers of water quality. Simulium maculatum

(Meigen), for example, once widespread in central

Europe, was extirpated from many large rivers

because of pollution (Zwick & Crosskey, 1981).

Where pest species persist or thrive in the face of

human activity, various means have been used to

control their populations. Historically, chlorinated

hydrocarbons such as DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichlo-

roethane) and methoxychlor were used against black

fly larvae. Neither compound was specific to black

flies, and both were susceptible to resistance prob-

lems. DDT was discontinued in the early 1970s

because of its devastating impact on the environment

(i.e., bioaccumulation), and methoxychlor and the

organophosphate Abate fell into disfavor because of

resistance and nonspecificity (Adler et al., 2004).

Currently, the biological control agent Bacillus

thuringiensis variety israelensis (Bti)—a naturally

occurring bacterium—is the remedy of choice against

black flies worldwide. Unlike its chemical predeces-

sors, Bti has an excellent host specificity, is highly

toxic to larval black flies, is safe for humans, and is

relatively inexpensive.

References

Adler, P. H., 2005. Black flies, the Simuliidae. In W. C.

Marquardt (ed.), Biology of Disease Vectors, 2nd edition.

Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego, CA: 127–140.

Adler, P. H., D. C. Currie & D. M. Wood, 2004. The Black

Flies (Simuliidae) of North America. Cornell University

Press, Ithaca, NY: 941.

Craig, D. A., D. C. Currie & P. Vernon, 2003. Crozetia

(Diptera: Simuliidae): redescription of Cr. crozetensis, Cr.

seguyi, number of larval instars, phylogenetic relation-

ships and historical biogeography. Zootaxa 259: 1–39.

Craig, D. A. & D. A. Joy, 2000. New species and redescrip-

tions in the central-western Pacific subgenus Inseliellum

(Diptera: Simuliidae). Annals of the Entomological

Society of America 93: 1236–1262.

Crosskey, R. W., 1990. The Natural History of Blackflies. John

Wiley, Chichester, U.K.: 711.

Crosskey, R. W. & T. M. Howard, 2004. A Revised Taxo-

nomic and Geographical Inventory of World Blackflies

(Diptera: Simuliidae). The Natural History Museum,

London. http://www.nhm.ac.uk/research-curation/projects/

blackflies/ (accessed 28 September 2006).

Currie, D. C., 1986. An annotated list of and keys to the

immature black flies of Alberta (Diptera: Simuliidae).

Memoirs of the Entomological Society of Canada 134:

1–90.

Currie, D. C., 1988. Morphology and systematics of primitive

Simuliidae (Diptera: Culicomorpha). Ph.D. thesis,

University of Alberta, Edmonton. 331 pp.

474 Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:469–475

123

Currie, D. C. & D. Grimaldi, 2000. A new black fly (Diptera:

Simuliidae) genus from mid Cretaceous (Turonian)

Amber of New Jersey. In D. Grimaldi (ed.), Studies on

Fossils in Amber, with Particular Reference to the

Cretaceous of New Jersey. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden,

The Netherlands: 473–485.

Dumbleton, L. J., 1973. The genus Austrosimulium Tonnoir

(Diptera: Simuliidae) with particular reference to the New

Zealand fauna. New Zealand Journal of Science 15(1972):

480–584.

Henderson, C. A. P., 1986. Homosequential species 2a and 2b

within the Prosimulium onychodactylum complex (Diptera):

temporal heterogeneity, linkage disequilibrium, and

Wahlund effect. Canadian Journal of Zoology 64: 859–866.

Kalugina, N. S., 1991. New Mesozoic Simuliidae and Lepto-

conopidae and blood-sucking origin in lower dipterans.

Paleontologichesky Zhurnal 1991: 69–80. [In Russian

with English summary].

Mackerras, I. M. & M. J. Mackerras, 1952. Notes on Austral-

asian Simuliidae (Diptera). III. Proceedings of the

Linnean Society of New South Wales 77: 104–113.

Malmqvist, B., R. S. Wotton & Y. Zhang, 2001. Suspension

feeders transform massive amounts of seston in large

northern rivers. Oikos 92: 35–43.

Malmqvist, B., P. H. Adler, K. Kuusela, R. W. Merritt & R. S.

Wooton, 2004. Black flies in the boreal biome, key

organisms in both terrestrial and aquatic environments: a

review. E

´

coscience 11: 187–200.

Moulton, J. K., 2000. Molecular sequence data resolves basal

divergences within Simuliidae (Diptera). Systematic

Entomology 25: 95–113.

Peterson, B. V., 1981. Simuliidae. In J. F. McAlpine, B. V.

Peterson, G. E. Shewell, H. J. Teskey, J. R. Vockeroth, &

D. M. Wood (eds.), Manual of Nearctic Diptera, vol. 1,

Monograph No. 27. Research Branch, Agriculture

Canada, Ottawa: 355–391.

Takaoka, H., 2003. The Black Flies (Diptera: Simuliidae) of

Sulawesi, Maluku and Irian Jaya. Kyushu University

Press, Fukuoka, Japan: 581.

Zwick, H. & R. W. Crosskey, 1981 [‘‘1980’’]. The taxonomy

and nomenclature of the blackflies (Diptera: Simuliidae)

described by J. W. Meigen. Aquatic Insects 2: 129–173.

Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:469–475 475

123

FRESHWATER ANIMAL DIVERSITY ASSESSMENT

Global diversity of mosquitoes (Insecta: Diptera: Culicidae)

in freshwater

Leopoldo M. Rueda

Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2007

Abstract Mosquitoes that inhabit freshwater habi-

tats play an important role in the ecological food

chain, and many of them are vicious biters and

transmitters of human and animal diseases. Relev ant

information about mosquitoes from various regions

of the world are noted, including their morphology,

taxonomy, habitats, species diversity, distribution,

endemicity, phylogeny, and medical importance.

Keywords Mosquitoes Culicidae

Diptera Freshwater Diversity

Introduction

Mosquitoes are important groups of arthropods that

inhabit freshwater habitats. Their role in the ecolog-

ical food chain is well recognized by many aquatic

ecologists. They are prominent bloodsuckers that

annoy man, mammals, birds and other animals

including reptiles, amphibians, and fish. They are

probably the most notoriously undesirable

arthropods, with respect to their ability to transmit

pathogens causing human malaria, dengue, filariasis,

viral encephalitides, and other deadly diseases. They

are also known for being irritating biting pests.

Sometimes, their nuisance bites are so severe that

they make outdoor activities almost impossible in

many parts of the world. Many large coastal areas are

made unbearable by salt marsh mosquitoes, and the

real estate development and the tourism industry are

also seriously affected. More than a hundred species

of mosquitoes are capable of transmitting various

diseases to humans and other animals. Anopheles

mosquitoes, for example, solely transmit malaria. It is

undoubtedly the most serious arthropod vector-borne

disease affecting humans. About 90% of all malar ia

deaths in the world occur in Africa, south of the

Sahara. This is because the majority of infections in

Africa are caused by Plasmodium falciparum, the

most dangerous of the four human malaria parasites.

It is also due to the fact that efficient malaria vectors

(e.g., Anopheles gambiae Giles) are widesp read in

Africa and are very difficult to control. In many parts

of the world, the indirect effect of malaria and

mosquito-borne diseases in lowered vitality and

susceptibility to other non-vector-borne diseases

accounted for more deaths as well as reduced

production following work losses.

This chapter presents the current information on

the morphology, taxonomy, habitats, species diver-

sity, phylogeny, distribution, endemicity, and medical

importance of the various groups of mosquitoes

Guest editors: E. V. Balian, C. Le

´

ve

ˆ

que, H. Segers

and K. Martens

Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment

L. M. Rueda (&)

Walter Reed Biosystematics Unit, Department of

Entomology, WRAIR, MSC MRC 534 Smithsonian

Institution, 4210 Silver Hill Road, Suitland, MD 20746,

USA

e-mail: ruedapol@si.edu

123

Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:477–487

DOI 10.1007/s10750-007-9037-x

worldwide. It is not the intention of this work to

comprehensively review all major topics mentioned

above. Selected references are included, and should

be consulted for further reading.

General morphology

Mosquitoes, like any arthropods, are bilaterally sym-

metrical. The adult mosquito (Fig. 1A) is covered with

an exoskeleton, and its body is divided into three

principal regions: the head, thorax, and abdomen. The

head is ovoid in shape, with large compound eyes. It

bears five appendages, which consist of two antennae,

two maxillary palpi and the proboscis. The thorax,

the body region between the head and abdomen,

is composed of three segments, the prothorax,

mesothorax, and metathorax. Each segment has a pair

of join ted legs; in addition, the mesothorax has a pair

of functional wings, and the metathorax, a pair of

wings represented by knobbed structures called hal-

teres. The abdomen is composed of 10 segments, of

which the three terminal segments are specialized for

reproduction and excretion. Apparently, the mosquito

adults resemble Chironomidae, Dixidae, Chaoboridae,

and other Nematocera, which like mosquitoes have

aquatic immature stages. Mosquitoes, however, are

distinguished from such similar looking dipterous flies

by the presence of scales on the wing veins and wing

margins, and by their forwardly projecting long

proboscis that is adapted for piercing and sucking. In

contrast to an adult, the larva (Fig. 1B) is largely

composed of soft, membranous tissues in the thorax

and abdomen, and hardened, sclerotized plates in the

Fig. 1 (A) Mosquito adult female, Anopheles sinensis, lateral view. (B) Mosquito larvae, An. sinensis, dorsal view. ( C) Mosquito

habitat, creek. (D) Mosquito habitat, irrigation ditch

478 Hydrobiologia (2008) 595:477–487

123