Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

356 Freedom Riders

were frequent and undoubtedly justified, some of the Riders, especially those

from poor or working-class backgrounds, felt that such complaints smacked

of bourgeois privilege and were inappropriate in a movement of mass libera-

tion. On several occasions individuals or groups of Riders called for a general

hunger strike and total noncooperation with prison authorities “until the food

gets better,” but no such strike ever materialized, even during the salt epi-

sode. Interestingly enough, the hunger strikes that did occur had more to do

with individual conscience and Gandhian strategy than inedible food. And

even the philosophically based hunger strikes led to disagreements about the

etiquette and timing of prison-constricted protest. “Those who went on long

fasts,” Bill Mahoney recalled, “justified Gandhi’s remark that at times he had

to fast in spite of his followers’ refusal to join him; others, who would fast

only when there were numbers large enough to be politically effective, said

that they took this stand in accord with Gandhi’s practice of only making

meaningful sacrifices.”

Most of the hunger strikes at Parchman—unlike the earlier fasts at the

Jackson and Hinds County jails—were short-lived and unpublicized, but there

were a few exceptions. After Ken Shilman, an eighteen-year-old white Free-

dom Rider from Long Island, posted bond on June 20, he told the press that

three of his fellow inmates were conducting a prolonged hunger strike to

protest the inhumane conditions at Parchman. One of the hunger strikers,

Price Chatham, a twenty-nine-year-old white Rider from East Rockaway,

New York, had begun his fast in Jackson on June 2 and had not eaten for

nearly three weeks. According to Shilman, Chatham’s weight had dropped

from 150 to 120 pounds, endangering his health. Prison authorities disputed

Shilman’s claim, insisting that Chatham was actually sneaking food from other

prisoners and had lost only two and a half pounds during his so-called fast.

To prove their point, they placed Chatham in solitary confinement on June

23, a move that brought his fast to an end three days later. Whatever the

truth of Shilman’s claims on behalf of his friend, the episode demonstrated

the difficulty of using a hunger strike to send a message from Parchman to

the outside world.

16

Fortunately, there were other means of reaching beyond the prison’s

walls. While personal visitors were prohibited, carefully monitored contact

with visiting ministers, rabbis, and priests was allowed. And even though

letters to and from the Freedom Riders were routinely censored by prison

authorities, some Riders developed elaborate codes to foil the censors. Oth-

ers relied on the periodic release of individual Riders as a means of delivering

messages to friends and family members or of publicizing what was going on

at Parchman. Shilman’s description of the inhumane conditions in the maxi-

mum security wing was only the first of several exposés offered by recently

released Freedom Riders. After posting bond on June 29 and returning to his

home in Victoria, British Columbia, Michael Audain gave the press a de-

tailed briefing on the treatment being dispensed at Parchman, including the

Ain’t Gonna Let No Jail House Turn Me ’Round 357

removal of the mattresses and the use of “wrist breakers,” viselike metal clamps

that administered excruciating pain when tightened. “I would not describe it

as torture,” Audain told reporters, with a touch of sarcasm, “because I do not

know the precise definition of that word, but I would at least say it was very

brutal treatment.”

After posting bond on July 3, Jim Farmer issued similar charges during

an emotional Independence Day press conference in Jackson. Joined by CORE

field secretary Jim McCain, Farmer held forth on the situation at Parchman

and on the movement’s plans for the future—and he did not hold back on

either front. After predicting that his experiences at Parchman would prove

valuable to CORE’s efforts “to orient new riders about what to expect there,”

he confessed that his time in prison had “tried my faith in human nature.”

Judging by what he had seen and experienced, “the policy of the prison is the

dehumanization of the riders, to make us as animals.” Prison authorities had

violated the Riders’ civil rights at every turn, Farmer insisted, and Superin-

tendent Fred Jones was well aware of what was going on. When asked to

respond to the charges by Farmer and others, Jones simply grinned and said

he had never intended “to turn the prison into a country club.” Referring to

the mattress episode, he declared that “a penitentiary must have some order

and discipline. . . . This is a bunch of trouble makers . . . who came here to

make trouble. They thought they could come down here and take over, but

they’re not going to take over as long as I’m here.”

17

Such explanations drew wry smiles from local reporters and other white

Mississippians, but they did not dispel the growing suspicion that the Free-

dom Riders were being systematically mistreated at Parchman. On the day of

Farmer’s release, Minnesota governor Elmer Andersen ordered the head of

the state Human Rights Commission, Wright Brooks, to conduct an investi-

gation of the conditions at Parchman. Two weeks earlier the families of the

six Minnesota Freedom Riders arrested and jailed in Mississippi had asked

Anderson to help them gain access to their children, but Anderson’s appeal

on their behalf had gotten nowhere. Frustrated by Ross Barnett’s seeming

indifference to the parents’ concerns, he eventually decided to send Brooks

and Assistant Attorney General John Casey Jr. to Mississippi for a “first-

hand look at the situation.”

When the two Minnesota officials arrived in Jackson on July 6, a defiant

Barnett placed severe restrictions on the investigation. While the Minneso-

tans “would be permitted to view jail facilities in Jackson, Hinds County and

at Parchman” and talk with the jailed Minnesota Riders for “about five min-

utes,” they would not be allowed to conduct an extended inspection of penal

conditions. Mississippi had nothing to hide, Barnett assured Brooks and Casey,

pointing out that earlier in the week a local judge had asked a Hinds County

grand jury to visit Parchman on a fact-finding mission. Indeed, Barnett even

arranged for the Minnesotans to take a tour of Jackson State College and

other “Negro facilities” to demonstrate how much racial progress had been

358 Freedom Riders

made in recent years. Nevertheless, when the two officials arrived at Parchman

they were given only a cursory look at the prison’s cell blocks and only a

brief, tightly monitored visit with their fellow Minnesotans. With most of

their scheduled time at Parchman taken up by a lavish dinner with Superin-

tendent Jones and his wife, they had little chance to gather the kind of de-

tailed information that they had been told to gather. Predictably, their

subsequent report was noticeably lacking in specifics and of little value to

Governor Anderson or the worried parents back in Minnesota. In fact, to the

dismay of movement leaders, the report all but absolved Mississippi prison

officials of any wrongdoing. Brooks told reporters upon her return to Min-

nesota: “A tour of the prison facilities has convinced me that there have been

no examples of mistreatment or abuse.” Other than a few complaints about

the food and requests for more exercise, there were allegedly no problems to

report. Claire O’Connor, who posted bond and returned to Minnesota just

prior to Brooks’s visit, presented a darker version of Parchman to anyone

who would listen. But her personal testimony had little impact on the official

response to the plight of the Minnesota Six.

18

BOTH THEN AND LATER SOME OBSERVERS suspected that the Brooks Report

was a whitewash. But others concluded that the report accurately reflected

the treatment accorded white Freedom Riders. The treatment of black Rid-

ers, it was commonly assumed, was far worse—not an unreasonable assump-

tion considering Parchman’s unrivaled reputation for racial oppression.

Notorious for breaking both the spirit and the flesh of black men, Parchman

epitomized a criminal justice system dedicated to the interests of racial con-

trol and exploitation. Forged in the image of Mississippi’s caste system, it

was a plantation masquerading as a prison, a place where the state’s least

fortunate black laborers went to suffer and die. Thus, even though whites

also suffered and sometimes died there, the mystique of Parchman was gen-

erally more intense for black prisoners. This is not to say that the white Free-

dom Riders who spent time at Parchman felt safe and secure. On the contrary,

in the aftermath of the assaults in Birmingham and Montgomery there was

no longer any doubt that under certain conditions white segregationist rage

could fixate just as easily on white transgression as on its black equivalent.

Indeed, the brutal beatings of Jim Peck, Jim Zwerg, and Walter Bergman indi-

cated that at least some segregationists were capable of a special rage when

confronted by white civil rights activists. Still, not even these harrowing events

could overturn the conventional wisdom that the institutional manifestations

of white supremacy were more dangerous for blacks than whites.

This was certainly true of the Freedom Riders themselves, many of whom

felt extremely uncomfortable about the imposed racial segregation in Missis-

sippi jails and prisons. At Parchman, all of the Freedom Riders, black and

white, lived in the same maximum security unit, but the unit’s individual

cells were rigidly segregated. While blacks and whites sometimes found them-

Ain’t Gonna Let No Jail House Turn Me ’Round 359

selves in adjoining cells, they were not allowed to share the same living quar-

ters. In such a Jim Crow setting, differential treatment of some kind was

virtually inevitable, even though the basic physical conditions of food, cloth-

ing, and shelter seem to have been the same for both races. How meaningful

these differences were to those who suffered relative deprivation probably

varied from individual to individual, and from cell to cell, but the racialized

nature of the overall Parchman experience was, at the very least, an unfortu-

nate reality that interrupted the rising interracialism of the nonviolent move-

ment. Denied the opportunity to practice racial integration in prison, black

and white Riders were prevented from practicing what they preached.

19

The separation of male and female Freedom Riders was an additional

source of guilt and anxiety. Both in the Hinds County and Jackson jails and

at Parchman, the female Riders faced many of the same problems and condi-

tions as the men—racial segregation, bad food, monotony, and even the re-

moval of their mattresses—but they also had to deal with persistent fears

related to gender and sexual vulnerability. While several had been arrested

before, none had spent more than a few days behind bars. Nor did any of

them have any extended experience with an artificial environment detached

from the traditional world of men and women. Virtually all of the female

Riders, black or white, had been reared in families where some man or woman,

either a father or a mother, or perhaps an older brother or sister, assumed

the role of custodian; and most had an array of other protectors, friends both

male and female, who constituted an extended support system that could be

called upon in time of need. None of this was available to them in the jails of

Mississippi, where normal patterns of both “feminine” and dependent be-

havior lost meaning and relevance. At one time or another, insecurity and

anomic disorientation plagued almost all of the jailed Freedom Riders, male

or female. But, in the pre-sexual-revolution context of the early 1960s, prob-

lems related to privacy, hygiene, and personal security often held a special

significance for women.

Of course, what made them especially vulnerable was not so much gen-

der per se as it was the assumption that they had crossed the boundaries of

racial and sexual decency. In the Deep South, women often found them-

selves on a cultural pedestal of affection and sentimental deference, but there

was no room on this pedestal for women who abandoned the shibboleths of

regional orthodoxy. In the calculus of patriarchal traditionalists, white women

who collaborated with black men to attack the cultural mores of the South

did not deserve to be treated as women, much less ladies. Neither did black

women who violated Southern conventions from the opposite direction.

Female transgressions, even when they were essentially political, could sel-

dom be separated from the broader assault on white supremacy. To many

white segregationists, women riding on buses with men of another race was

a sexually provocative act that could not be ignored or forgiven. To them,

the very fabric of civilization was at stake, and the women involved deserved

360 Freedom Riders

punishment harsh enough to deter other women from straying from the fold.

Such attitudes seemed to be especially common among white Mississippians,

who could turn even the most casual conversation about the Freedom Rides

into a discourse on miscegenation. William Kunstler had been in the state

less than a week when he encountered this fixation during a visit to Governor

Barnett’s office. After learning that Kunstler was both an ardent integration-

ist and the father of two daughters, Barnett could not resist asking the ques-

tion: “Mr. Kunstler, what would you think if your daughter married a dirty,

kinky-headed, fieldhand nigger?” Stunned by Barnett’s language, Kunstler

shot back that his daughter, like all American women, had “the right to select

her own husband.” Unmoved, Barnett warned the New York lawyer that the

real goal of the civil rights movement was intermarriage. “That’s all the niggers

want,” the governor insisted.

From the moment they arrived in Mississippi, the female Riders had to

deal with variations of this theme, including the insinuation that they were

fallen women who had joined the movement as a sexual lark. Whatever their

actual behavior, they were treated as little more than civil rights whores.

While there is no evidence that any of the women were raped—a violation

that was probably precluded by the glare of publicity surrounding the Free-

dom Riders—other sexual indignities were common. For Carol Ruth Silver,

a white Freedom Rider from New York who kept a detailed diary during her

six weeks of incarceration in Mississippi, the undercurrent of sexual suspi-

cion became palpable when detectives interrogated her the day after her ar-

rest. With no apparent justification, she was bombarded with questions about

interracial sex. Had she ever dated “Negro boys”? Would she be willing to

marry a Negro? Over the next few weeks, such questions would become al-

most routine for Silver and the other female Riders.

Insulting and unwelcome questions represented only a small part of the

sexually related intimidation that the women were forced to endure. After

their arrival at Parchman, the female Riders had to deal with male guards

who could not resist watching them undress and shower and with a prison

doctor who conducted invasive and unnecessary vaginal examinations. The

strong suspicion that the doctor used the same cloth glove for all the women

he examined added to the feeling of victimization and served as a symbol of

the prison staff’s contempt for the female Riders. During most of their stay

at Parchman, the female Riders were placed under the collective supervision

of one male guard, one matron, and a staff of female trusties. In actuality,

though, they received little attention from prison authorities, other than the

delivery of daily rations. On several occasions the guards and trusties all but

ignored requests for medical attention, including one instance in which a

young California Freedom Rider, Janice Rogers, suffered a miscarriage.

This was Parchman at its worst. Fortunately, there was another side to

the women’s saga. As one of the first female Riders to be transferred to Parch-

man, Silver was able to experience—and to chronicle—not only the hard-

Ain’t Gonna Let No Jail House Turn Me ’Round 361

ships and indignities of prison life but also the evolution of resistance and

community in the women’s section of the maximum security unit. Like the

male Freedom Riders who lived at the opposite end of the unit, the women

were racially segregated and housed in small six-foot by nine-foot cells. Un-

like the men, however, the women were crowded into a tight cluster of thir-

teen cells that provided opportunities for considerable interaction and

collaboration. Thus for them the Parchman experience took on a more col-

lective cast than the cell-by-cell pairings that dominated prison life among

the men. Perhaps for this reason, the women, even more than the men, were

able to turn Parchman into a makeshift school of political education and

cultural enrichment. In addition to endless rounds of freedom songs, female

Freedom Riders organized nonviolent workshops, political seminars, ballet

lessons, French classes, and even a series of lectures on Roman history and

Greek mythology. Not all of the women participated in these activities, and

prison life was never easy for the female Riders. But the stories of resilience

and ingenuity that appear in Silver’s diary and other sources stand as a testa-

ment to the female Riders’ determination to make the best of a difficult situ-

ation. While some of the women found Parchman unbearable and posted

bond as soon as bail money became available, many others stuck it out for a

month or more, creating a saga of survival that became a staple of movement

lore. Often condescended to as the “weaker sex,” they very nearly proved the

opposite during the first “freedom summer” at Parchman.

20

At the same time, women prisoners, like their male counterparts, discov-

ered the difficulty of reaching a consensus in a group that spanned a wide

range of cultural backgrounds and personal philosophies. Even before they

arrived at Parchman, the cancellation of a planned hunger strike caused hard

feelings among several of the female Riders. On June 14, after learning that

many of the male Riders were about to be transferred to Parchman, eleven of

the women at the Hinds County Jail agreed “to go on a hunger strike until

the boys come back or we are sent there.” Selecting Pauline Knight, a twenty-

year-old black student from Nashville, as their designated spokesperson, the

eleven women began a fast that within a day caused one of them, Winonah

Beamer—a nineteen-year-old white Rider from Ohio—to faint and others to

question how long they could hold out. Though several of the hunger strik-

ers were determined to make good on their pledge, the strike quickly col-

lapsed when attorney Jack Young persuaded Knight that fasting in a Mississippi

jail was a waste of time and energy. Before the end of the second day, Knight

had announced that as far as she was concerned the strike was over, a deci-

sion immediately seconded by Ruby Doris Smith and at least two other black

Riders. Among several of the white hunger strikers, however, Knight’s state-

ment engendered considerable resentment. As Silver chronicled in her diary:

“All eleven of us had considered very carefully the value, implications, etc.,

of this strike, its objectives and purpose and how it should be run. We felt a

great deal of resentment against Pauline for not having consulted with us in

362 Freedom Riders

the first place. . . . We had all felt very strongly that the spokesman for the

strike and the leadership of it should come from one of the Negro girls rather

than from one of us in this cell, but we also felt that as individuals equally

with them involved in a democratic movement, we had at least the right to be

treated equally.”

21

This was not the last time that hard feelings and misunderstandings would

disrupt the solidarity of the women Riders, and the necessity of compromise

and cultural negotiation became one of the prime lessons of the prison expe-

rience. But with the women, as with the men, the problem of bridging racial

and philosophical gaps never reached the level of a true crisis. While several

incidents foreshadowed the deep divisions that would plague the movement

later in the decade, the newness of the experience and the relative innocence

of the Riders, male and female, seemed to foster a spirit of cooperation that

eliminated the worst manifestations of suspicion and distrust. Though the

Riders were flesh-and-blood human beings and hardly infallible, the com-

mon ground of the emerging freedom struggle provided a foundation for

generosity and forgiveness that few movements, before or since, have been

able to match. On a number of occasions strong feelings and tactless state-

ments led to frayed nerves and even angry outbursts, but with few exceptions

the Riders seemed to be able to absorb whatever barbs came their way with a

measure of disarming grace or humor.

Even the acerbic Stokely Carmichael generally produced more comic

relief than meanness when he tangled with other Riders. Steve Green, for

one, discovered the comic side of Carmichael during his first week at

Parchman. After Green introduced himself as a student at Middlebury and

offered an “exuberant” prediction that “hundreds if not thousands of college

students . . . would head to Jackson when the school year ended,” Carmichael,

the son of struggling West Indian immigrants, yelled out: “Hey, guys, did

you hear that? We just need to hold on here until Harvard, Yale, and Princeton

let out, and then there’s going to be an invasion of the Deep South by rich

white kids.” Momentarily stung by Carmichael’s sarcasm, Green managed

only a perfunctory response that was drowned out by gales of laughter. But it

didn’t take him long to develop respect for Carmichael’s hard-earned cyni-

cism. “Stokely was a bit rough,” Green acknowledged in a candid memoir of

his Parchman experience, “but then, as later, he was mostly right.” In John

Lewis’s memory, Carmichael was the most argumentative of the Freedom

Riders in Parchman. With his strong views and sharp tongue, he could be an

unsettling influence, and his challenges to what he viewed as a misguided

faith in Gandhian sacrifice often irritated Lewis and others. Carmichael’s

dissent did not, however, lead to serious disruption or consistent factional-

ism. During the mid-1960s his fervent advocacy of “Black Power” would

have major consequences and effectively split the movement, but in 1961

there was no such cleavage.

Ain’t Gonna Let No Jail House Turn Me ’Round 363

For Green, Lewis, and Carmichael, as for Silver and Knight, prison was

not so much a battleground as it was a testing ground where generalizations

and stereotypes related to race, class, region, and religion could be examined

and reconsidered. As Carmichael later recalled: “What with the range of

ideology, religious belief, political commitment and background, age, and

experience, something interesting was always going on. Because, no matter

our differences, this group had one thing in common, moral stubbornness.

Whatever we believed, we really believed and were not at all shy about

advancing. We were where we were only because of our willingness to af-

firm our beliefs even at the risk of physical injury. So it was never dull on

death row.” For many of the Riders, the time at Parchman represented their

first extended experience with exotic allies—movement activists who had

grown up in places that they had read about but never visited. Freedom

Riders of all descriptions—blacks and whites, Northerners and Southern-

ers, Christians and Jews, working-class laborers and relatively privileged

students—discovered firsthand that the freedom struggle was a movement of

multiple and shifting perspectives. In such a setting, they could not help but

learn from each other. Indeed, despite the artificial constraint of racially seg-

regated cells, they all shared enough of the dangers and challenges of mass

incarceration to develop a level of mutual respect that would have been im-

possible under less authoritarian circumstances.

This was not, of course, what Ross Barnett and his lieutenants had in-

tended. But, like the imposed institutionalization of Jim Crow in the early

twentieth-century South, the mass incarceration of Freedom Riders at

Parchman had unintended consequences for a movement that had long suf-

fered from organizational disunity and fragmentation. Not only did the un-

resolved crisis at Parchman provide a temporary focus for the movement at

large, but also the personal dynamics of the drama being played out in the cells

and corridors of the prison acted as a unifying force among the Freedom

Riders themselves. Organizationally, the Freedom Rider coalition remained

a fragile entity. Indeed, the cooperative spirit among the Riders at Parchman

suggested that a meaningful convergence of CORE, SNCC, SCLC, and the

Nashville Movement was more likely to take place inside the walls of a prison

than outside. Why this was so is difficult to explain, but in a state renowned

for paradox and irony the prison-based maturation of a democratic social

movement somehow seems fitting.

22

WHATEVER THEIR ULTIMATE SIGNIFICANCE, the unexpected benefits derived

from the gathering at Parchman were not apparent enough at the time to

alter the movement’s strategy of challenging the constitutionality of the Free-

dom Riders’ arrests and imprisonment. Having already proven that they could

mobilize hundreds of activists willing to go jail for their beliefs, movement

leaders saw little advantage in prolonging the struggle. In addition to the

obvious injustice involved, Mississippi’s policy of fining Freedom Riders and

364 Freedom Riders

sentencing them to long jail terms placed a heavy legal and financial burden

on CORE, which continued to bear the primary responsibility for under-

writing and sustaining the Freedom Rider movement. In effect, Mississippi’s

decision to arrest the Freedom Riders had initiated a war of attrition, a con-

test between the state’s ability to accommodate wave after wave of Riders

and the movement’s capacity to sustain them, financially and otherwise. As

of early July the outcome of this struggle was still very much in doubt, and

Farmer and others worried that the movement’s greatest challenges lay ahead.

To this point much of the financial cost had been postponed by the Riders’

decision to forgo bail, but this favorable situation was about to end, thanks to

a provision of Mississippi’s disorderly conduct statute that required the jailed

Riders to post bond within forty days of conviction. Riders who missed this

deadline lost their right of appeal and any alternative to serving out their

entire sentence. In this context, posting bond on the thirty-ninth day became

an essential part of the Riders’ legal challenge to Mississippi’s Jim Crow sys-

tem. The day of reckoning varied depending on the date of conviction, but

for the first group of Riders—those convicted on May 26—the thirty-ninth

day was Tuesday, July 4. While more than a third of the first group had

already posted bond, fifteen remained in jail as the deadline approached.

The first mass bailout, which actually took place on July 7 due to proce-

dural delays, brought joy and liberation to the Freedom Riders involved. But

it also represented an ominous development for a movement perpetually short

of funds. For each Freedom Rider, bond was set at five hundred dollars, but

that was only the beginning of the financial burden imposed by litigation. In

addition to the bond payment, CORE had to come up with enough money

to provide each Freedom Rider with a defense attorney, transportation back

home, and, at some time later in the summer, transportation back to Missis-

sippi for an appellate trial. When combined with court costs, housing costs,

the purchase of bus and train tickets for the actual Freedom Rides, and other

miscellaneous outlays, the average cost per Freedom Rider was well over a

thousand dollars. CORE had raised a considerable amount of money since

late May, prompting Marvin Rich, the organization’s financial coordinator,

to exclaim in a letter to Farmer in early June: “More and more freedom rid-

ers should be moving toward Jackson in the next two weeks—and we have

the money to get them there!” But CORE leaders felt less flush by early July.

With more than a hundred Freedom Riders already in jail and the prospect

of hundreds more by the end of the summer, the projected budget required

to sustain the Freedom Rider movement had risen to more than a half mil-

lion dollars.

23

At his postrelease press conference in Jackson, Farmer was careful to

avoid any mention of CORE’s precarious financial situation. He was equally

discreet when he arrived at New York’s LaGuardia Airport the next day.

Greeted by his pregnant wife, Lula, his two-and-a-half-year-old daughter,

Tami, and more than a hundred friends and colleagues sporting buttons pro-

Ain’t Gonna Let No Jail House Turn Me ’Round 365

claiming “Freedom Now–CORE,” he was all smiles as he entered the termi-

nal. Standing in front of a large banner that read “Welcome Home, Big Jim,”

the crowd erupted into song as he rushed to embrace his family. “We Shall

Overcome,” they sang over and over again, giving reporters and other on-

lookers a glimpse of the movement’s soaring spirit. Later, after one of the

well-wishers in the crowd began singing a special version of the spiritual

“We Shall Not Be Moved,” the entire gathering joined in. “Farmer is our

leader, We shall not be moved,” they chanted. “Just like a tree that’s planted

by the waters, We shall not be moved.” Years later Farmer described the

scene as one of the high points of his life and a “dizzying” introduction to

national fame. As soon as he stepped off the plane, he felt as if he had been

thrust into an “Alice-in-Wonderland world.” “I was blinded by flashbulbs.”

he recalled. “Microphones were shoved into my face as newspersons jock-

eyed for position. Television cameras recorded my walk to the terminal as if

each step were a stride into history.” During his six weeks of isolation at

Parchman, he had developed some sense of the Freedom Rides’ widening

impact, but the realization that the project had already exceeded his wildest

expectations did not hit him with full force until he returned to New York.

As he told the reporters at LaGuardia, the Freedom Rides had unleashed a

transcendent feeling of hope and redemption that was stronger than any force

wielded by demagogic politicians or prison wardens. Despite the desperate

efforts of men like Ross Barnett and Fred Jones, the nonviolent movement

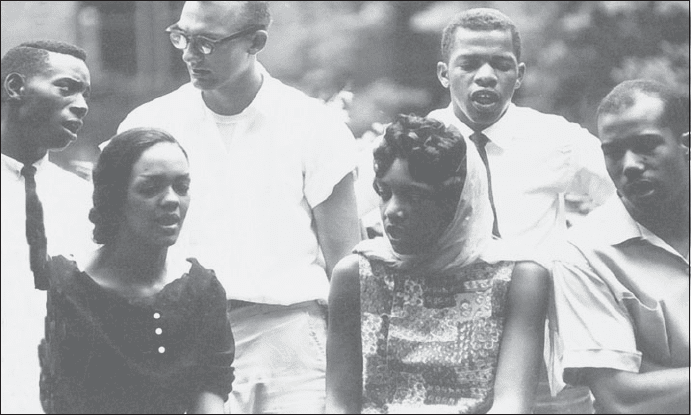

This picture was taken in July 1961 in Chicago, where these six Freedom Riders—

all Nashville Movement veterans—had gathered to raise funds for CORE. From

left to right: Bill Harbour, Lucretia Collins, Jim Zwerg, Catherine Burks, John

Lewis, and Paul Brooks. (Courtesy of Bill Harbour)